South Asia has been marred by constant intrastate conflict. Over the past few decades, sustained insurgency movements have proven detrimental to the health of the region and its people. This is the second article in series on the rise, fall, and triumph of South Asian insurgencies in three states in the region: Nepal, Sri Lanka, and India.

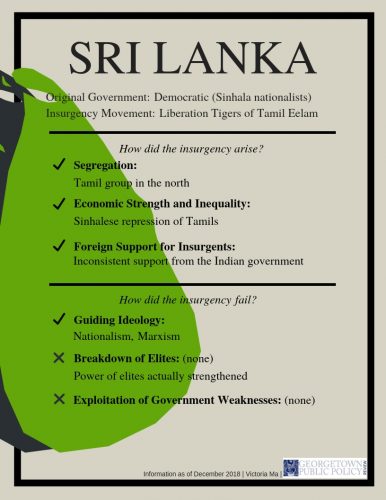

Part II: How insurgencies fail – Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka’s civil conflict has its origins in the country’s history with British colonialism. When colonizing Sri Lanka, the British favored a tea plantation economy that required a vast number of workers. To fulfill these demands, the British brought Tamils from the Southern region of India. While the ethnically Sinhalese elites benefited from colonization, the Tamil population did not enjoy the same economic prospects. Thus, by the time Sri Lanka gained independence, economic fortunes were split between the two ethnic groups: the economically prosperous Sinhalese majority and the poverty-stricken Tamil minority.

Post-independence, tensions between the two groups grew. In 1956, after a staunch Sinhalese-nationalistic leadership won the snap election, they introduced the official language act referred to as the “Sinhala Only” act that designated Sinhala as the only official language in the country. This, over time, created large problems for the Tamil population. The lack of private jobs in the country further intensified the problem as the public sector required individuals to know Sinhalese. The government, in addition to requiring the language for public sector jobs, also mandated the language as an entry requirement for secondary educational institutions. The Sinhala Only act drastically widened the gap between the Tamils and the Sinhalese in favor of the latter group.

As violence between the two ethnic groups started costing lives in the late 1950s, several agreements for greater political autonomy for Tamils in the north were reversed by numerous Sinhalese governments. In the early 60s, the Tamil political leadership launched nonviolent protest campaigns against the Sinhalese government. The government, in turn, responded violently, even declaring a state of emergency in the Tamil-dominated northern and eastern provinces.

Nevertheless, an independent Tamil state looked increasingly plausible by the early 1970s. Tamil-dominated areas in the north and the east became economic and agricultural centers despite being historically neglected by the government. As these areas became major rice producing regions, they contributed to a feeling that a Tamil state could be economically viable. The Tamils did not waste time to make the call for statehood.

The Sinhalese government responded with programs creating Sinhala agricultural settlements in Tamil-majority areas to change the demographics of these regions. The Tamils saw this as a flagrant maneuver to weaken the Tamil population and intensified their call for separation. These political and economic conflicts laid the causal basis for the insurgency to kindle in Sri Lanka.

The Sinhalese government also attempted to undermine the moderate Tamil political leadership by following a divide and rule strategy, which created disagreements among Tamil parties in their tactics vis-à-vis the government. While many followed a nonviolent path, others often called for stronger forms of resistance. Among these groups was Velupillai Prabhakaran’s Tamil New Tigers (TNT). From 1972 to 1975, TNT led an assassination campaign against government officials, which helped it gain popularity among Tamils and become a prominent militant group. Prabhakaran eventually changed the name of the TNT to the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) in May 1976 following a reorganization.

The ineffectiveness of the moderate Tamil leaders to advocate on behalf of their community also created space for radical groups to blossom. Most of these groups were Marxist in nature and envisioned idealistic outcomes from their struggle. Over time, their struggle leaned more towards radical nationalism. The LTTE was able to convince many Tamils that the only way to gain their freedom was to establish an independent Tamil state. The LTTE launched an all-out insurgency in 1983.

Beyond seeking independence, the LTTE also offered itself as an insurgent group pursuing extensive social and economic reforms within the Tamil community. Prabhakaran labelled his political views as “revolutionary socialism” with an aim of producing a more “egalitarian society.” When asked about the LTTE’s policy for their economy, Prabhakaran asserted that it would become an “open market economy.” But he noted that: “What form and what structure this economic system is to be instituted in can only be worked when we have a permanent settlement or independent state.” Over time, these insurgents formed their own police, judiciary and administrative systems. Prabhakaran himself, along with his LTTE cronies, established uncontested totalitarian control over some of the Tamil regions.

Beyond seeking independence, the LTTE also offered itself as an insurgent group pursuing extensive social and economic reforms within the Tamil community. Prabhakaran labelled his political views as “revolutionary socialism” with an aim of producing a more “egalitarian society.” When asked about the LTTE’s policy for their economy, Prabhakaran asserted that it would become an “open market economy.” But he noted that: “What form and what structure this economic system is to be instituted in can only be worked when we have a permanent settlement or independent state.” Over time, these insurgents formed their own police, judiciary and administrative systems. Prabhakaran himself, along with his LTTE cronies, established uncontested totalitarian control over some of the Tamil regions.

The Indian government also played a pivotal role in helping the LTTE insurgents. During the initial phase of the insurgency, India’s intelligence agency backed the Tamils with weaponry, training, and monetary support. Even as LTTE leaders were arrested in Tamil Nadu, the Indian government refused to extradite them to Sri Lanka.

The Government’s Success

While the situation initially seemed to have greatly favored the LTTE in launching and sustaining the insurgency for several decades, there are several factors that led to the government’s eventual success. First, President Mahinda Rajapaksa’s 2005 election created a sense of unity and political will within the Sri Lankan government. This did not exist previously, as there were factions within the political realm that wanted to prolong the war.

One example of unifying action by President Rajapaksa was appointing his brother as defense secretary, which allowed the two brothers to further cement the government’s militaristic approach to the insurgents. The pair greatly increased the size and budget of the military. From the start of the military campaign against LTTE in 2006 to when the war ended in 2009, military spending increased from 69.5 billion Sri Lankan rupees (approximately $380 million) to 177.1 billion rupees (approximately $970 million). Military personnel increased form 40,000 in 1987 to 220,000 by 2008. The government also improved its intelligence capabilities, which helped to blunt one of LTTE’s most effective tactics: suicide bombing. The LTTE was now facing a politically determined government with a much stronger military.

Concurrently, the Rajapaksa administration realized the need to win popular support. His government also focused on development initiatives, poverty reduction measures, and agricultural subsidies for poor farmers. These measures made financing the war difficult and the need for foreign financial support more important, but they were essential to convince the people that peace was worth fighting for. The measures worked. Prior to Rajapaksa’s administration, the Sri Lankan army struggled to recruit a mere 3,000 soldiers in a year; however, in the next three years, the army had been recruiting approximately 3,000 soldier per month.

Finally, India’s changing role in the conflict was pivotal. After 2005, the Indian government started providing vital intelligence to the Sri Lankan military regarding LTTE movements and warehouses, which helped to limit the LTTE’s arms shipments through seaports. As noted by Kumar Rupesinghe, India’s commitment towards the Sri Lankan government furthered after a large-scale terrorist attack across multiple locations in Mumbai in November 2008. Moreover, the Congress government in India also wanted the war to be over by 2009, as they planned on holding elections and did not want to annoy their Tamil allies in the country.

As the conflict wore on, the LTTE made a series of mistakes while also failing to capitalize on the government’s weaknesses. According to Rupesinghe, the LTTE’s greatest mistake came in 2009 with its “decision to take three hundred thousand civilians hostage, limit itself to less than two square miles of jungle…and engage in conventional warfare rather than use the guerrilla tactics that it had mastered over the years.” Towards the end of the war, the LTTE mainly aimed to resist the army’s advance. However, their strategic retreat, while seen as a way to save lives and resources, led to more defeats in light of Sri Lankan army’s renewed determination, greater resources and a scorched-earth campaign criticized by independent observers as resulting in massive human rights violations. The combination of these conditions led to the killing of Prabhakaran and brutal defeat of the group in May 2009.

***

Photo of female LTTE fighters by Wikipedia contributor Salix Oculus.

Ayush Manandhar is from Kathmandu, Nepal. His experiences include working with both government and international institutions, including the Embassy of Nepal in the United States, the United Nations Human Settlements Program, and Winrock International, among others. Recently, he served as the Fellow for Intercultural Engagement at his alma mater, Westminster College, where he led events and improved policies for the college’s minority students. As a student, he was the editor-in-chief of Westminster Journal for Global Progress, the flagship journal of the college. Having traveled widely and having seen people face widespread poverty and disparity, Ayush is motivated to uplift the lives of the many underprivileged people around the world. He hopes to write more on policy and politics as a part of this journey.

British historical document tell that Tamil were there

When British arrived, please learn the facts,

The article is factually incorrect or purposefully misleading the readers about the origin of eelam (srilankan) tamils . While its true that few tamils from India were brought to tea plantations of Srilanka by Britishers, large majority of tamils already lived there ever since Sinhaleese. The Chola empire ruled in eelam long before there were any britishers. the plantation(indian) tamils were not involved in the insurgencies , it was driven largely by eelam tamils who lived in their ancestoral regions of north east srilanka. (eelam)