If an online equivalent of the pre-digital age White Pages existed, would it be available to anyone who wanted to access it? A controversial policy of the D.C. Board of Elections may give us an answer — or, at least, a similar debate.

Two months ago, a minor controversy arose in the comment section of the popular D.C. blog PopVille. The subject was an unusual one for a blog that usually focuses on local restaurant openings and real estate listings: the availability of public records.

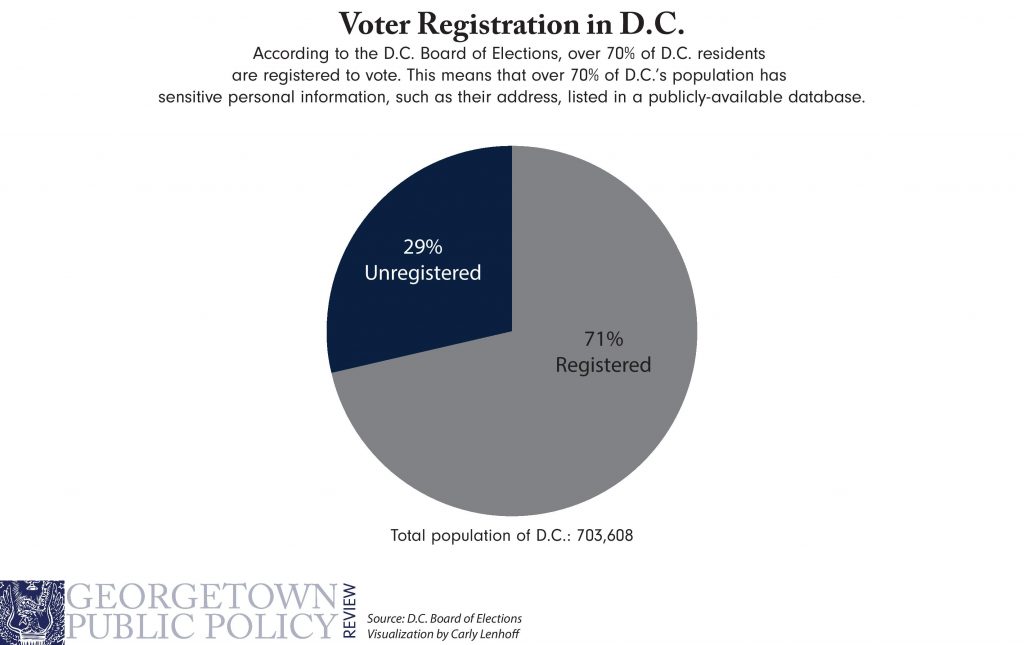

In advance of the 2018 midterm elections, the D.C. Board of Elections posted on its website a downloadable PDF listing of all registered voters, including information on their party registration, turnout over the last several elections, polling location, and place of residence. The file was removed in the weeks following the 2018 elections.

The D.C. Board of Elections is required by law to publish voting records. That a person’s voting status and jurisdiction is public knowledge is generally seen as a net positive for campaigns, political scientists, and the public. This kind of data is the primary mechanism by which erroneous registration files might be discovered — like in 2016, when Trump campaign advisor Steve Bannon was shown to be registered in both New York and Florida.

The point of contention in this situation was the publication of addresses. The dissemination of such personal information carries risks. For survivors of domestic violence and stalking, the publication of a home address — particularly in as much detail as the Board of Elections does, down to the apartment number — can introduce real danger or fear.

While homeowner information is generally publicly available, it isn’t usually published in an easily searchable online database. Information on occupants of rental properties, meanwhile, is published in no other public database. Virtually every state keeps a public voter file similar to this one, but D.C.’s practice of publishing the file online is unique. According to the Washington Post’s Brian Fung, even states like Florida, Colorado, and California — which all consider voter information to be a public record — still do not make such information generally available. The latter two go as far as to require formal requests for access or excluding home addresses from the list, respectively.

Of course, it was not always the case that the publication of addresses would turn heads. Many of us are old enough to remember when everyone’s names, addresses, and phone numbers were published in the White Pages and delivered to every household. What’s the difference, then, between a PDF published every election year and a book delivered periodically to people’s houses? Surely the former has even more advantages, like ease of searchability or even smaller environmental impact? Not necessarily.

In an era when the phone book was a common household item, people with good reasons to hide their addresses knew they needed to request to go unlisted. Compare that to the Board of Elections’ file release, which the vast majority of D.C. residents undoubtedly missed. While it’s possible to be removed from the list, it requires filing a court order under the newly established Address Confidentiality Program and proving that you’re a survivor of abuse or stalking.

These restrictions are sensible. If we keeping a public list of voters is in society’s best interest, it makes sense that there would be strict limitations on who can demand removal from the list. The public’s right to know who is voting in elections supersedes an individual’s right to privacy on that matter, unless the individual demonstrates a reasonable expectation that the erosion of privacy could cause them harm.

There’s a difference, though, between keeping a record public and placing it in an easily searchable online database. Publishing information online without restrictions gives the publisher less control over who reads it, for better and for worse. Recognizing when it serves the public good to cede this control is an essential skill that governments must develop in the 21st century.

A valuable precedent comes from the European Union, which has long recognized that internet access changes the nature of publicly available information. In 2014, the EU released the framework of its “right to be forgotten” policy. This allows citizens to limit the information about themselves that appears on Google and other search engines.

It’s an acknowledgment that the ease with which information is accessed online makes a real difference in the nature of a “public” record, and that regulations should reflect that reality.

This isn’t to say that governments should avoid making records available online. Generally speaking, easier, more centralized access to public records would be a force for good. The fewer barriers researchers, journalists, and law enforcement officers encounter in gathering data, the more time they have to analyze and investigate trends that might lead to important findings. But home addresses and other personal information should be treated with special care, and their publication in this manner is not justified by any immediately obvious public crisis in the voting and elections sphere.

State governments should make certain public records available to journalists or concerned citizens willing to fill out formal requests — leaving a paper trail of who has accessed the files — rather than allowing anyone with an Internet connection to access personal information. This wouldn’t guarantee bad actors are shut out from databases with personal information, but it provides a real paper trail and may deter some.

As currently practiced, D.C.’s policy of publishing home addresses in the voter file online is an affront to citizens’ privacy that may enable stalkers and other bad actors. The benefit to the public — having all voter histories public with no intermediate steps — does not justify this cost. The Board of Elections should either remove home addresses from the online file or institute barriers to access of the file that would create a paper trail for anyone who sought the information.

Photo by CC BY-SA HonestReporting.com, Flickr/ Freepress, with alterations

Pat is a writer, editor and general communications professional from Montpelier, Vermont. He works for the university and is on his way to becoming a double Hoya ('14, '19). Pat hopes to use his degree to help improve policy literacy in political communications.