As we enter the second year of the refugee crisis in southeast Bangladesh, solutions are slow to come and needs remain unmet. The rapid growth of at-risk refugee populations around the world has put international humanitarian institutions to the test, and a critical evaluation of how governments, humanitarian organizations and international institutions have handled the plight of the Rohingya people can serve as a valuable case study for how they manage other long-term refugee crises globally. Former GPPR editor Shane McCarthy traveled to Cox’s Bazar in Bangladesh to file this exclusive three-part series on the Rohingya. This is the first part.

By the time I arrived in the city of Cox’s Bazar in southeastern Bangladesh, the monsoon season had begun in full. Torrential rains pelted the city throughout the day as massive storm systems rolled onto the beach from the Bay of Bengal. The few remaining Bangladeshi tourists were undeterred and braved the weather, knowing they were close to their hotels. An hour’s drive south, close to a million Rohingya refugees were enduring the same conditions in whatever donated or makeshift shelters they had available.

The onset of the monsoon season presents another complication, albeit an anticipated one, to what is already a massive humanitarian undertaking. It also marks one year since violent reprisals by the military in Myanmar’s Rakhine state spurred the mass exodus of Rohingya refugees into Bangladesh. The intractability of the crisis and the growing frustration over limited solutions has instilled a mindset of entrenchment among the refugees in the camps, aid workers, and state actors alike. As time drags on, the desperate need for long-term policy and governance solutions becomes more pressing.

Because of a recent government crackdown on visits to the camps by outside observers, I was unable to travel to Kutupalong, home to the largest refugee camp outside Cox’s Bazar, or any of the other scattered camps to the south. However, by conducting interviews with local humanitarian actors based out of Cox’s Bazar, I gained insight into the current state of affairs and the challenges of managing such an environment, especially given the myriad of organizations working on the ground with often competing interests. Because of my sources’ association with groups currently working to manage the crisis, they will not be identified and the information that they provided will not be attributed.

Part One: The Plight of the Rohingya

“We are concerned to hear that numbers of Muslims are fleeing across the border to Bangladesh. We want to understand why this exodus is happening.” – Aung Sang Suu Kyi, September 2017

The Rohingya people have been described in humanitarian circles as the most persecuted people in the world. They are a Muslim minority within Buddhist Myanmar and lack formal citizenship under the 1982 Myanmar Citizenship Law, which effectively renders them stateless. For decades, Myanmar’s leaders have echoed the talking point that the Rohingya are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh rather than native inhabitants of the country. Unable to acquire a nationality, most Rohingya in Myanmar lack access to state education or civil service jobs and face restrictions in their freedom of movement. Persecution by the Myanmar authorities and their ethnically Burmese neighbors is not a new phenomenon, and hundreds of thousands of Rohingya had already fled to Bangladesh before the most recent crackdown in August of 2017.

Clashes between neighboring Muslims and Buddhists in Rakhine date back to the World War II, but the last several years saw an escalation in violence as entrenched Rohingya insurgents and Myanmar security forces engaged in tit-for-tat attacks. After an August 2017 raid by a Rohingya insurgent group on a police compound killed dozens of officers, the Myanmar military launched a brutal campaign in Rakhine state, the Rohingyas’ home state. Accounts from numerous survivors describe entire villages burned to the ground, the men mostly killed outright, and the women subjected to mass rape and imprisonment. Many witnessed the murder of their own family members, with victims as young as newborns. Some victims were burnt alive.

Confronted with the destruction of their people, most Rohingya saw no choice but exodus. According to the most recent estimates, around 700,000 Rohingya have crossed the border from Myanmar to Bangladesh since August 2017. Before the crackdown, the entire Rohingya population in both countries was fewer than one million people. Over half of the refugees are children. The vast majority are housed in the sprawling refugee camps that cover the landscape south of Cox’s Bazar, where they are recovering, rebuilding their lives, and waiting for justice.

“It’s like being thrown into the ocean with your hands and feet tied.” – A foreign aid worker in Cox’s Bazar describing the challenges of their work, July 2017

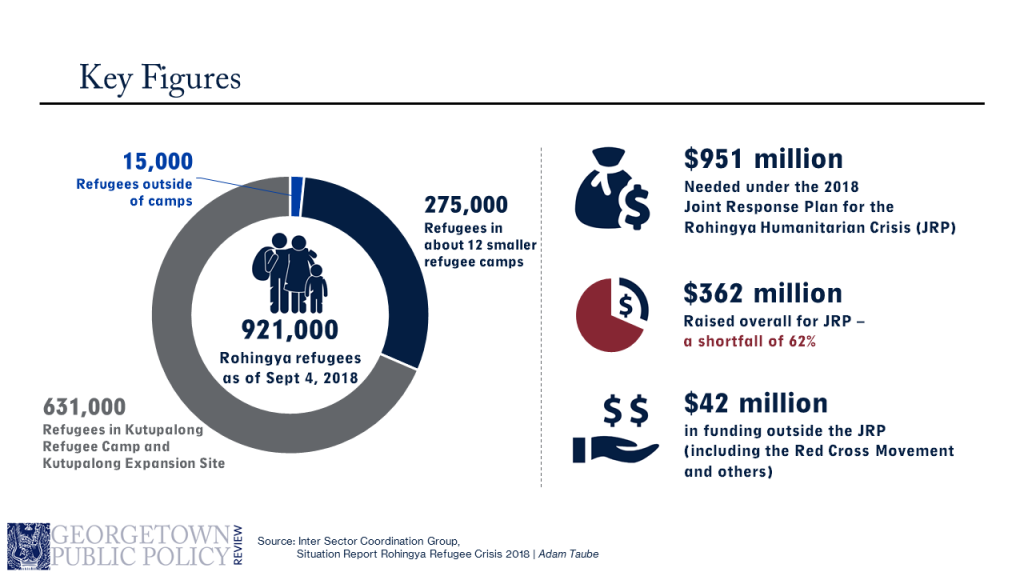

The world’s attention was drawn to the Rohingya after the atrocities committed against them came to light last year. However, as we enter the second year of crisis management, attention to the continuing needs of the refugees has waned, as has aid funding. For example, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) requested $182 million to provide aid through the end of 2018, but only secured $31 million. Pledges for the overall humanitarian effort are even worse: UN Secretary-General António Guterres has reported that out of the estimated $951 million needed for the full humanitarian aid plan, only 38 percent of funding had been met as of September.

Trafficking

Sex trafficking has historically been a concern among vulnerable populations, and the issue is becoming more rampant as time drags on. Underlying the spread of trafficking and sex work is the Rohingya people’s desperate search for a livelihood. For the most part, refugees are not allowed to leave the camp (although the borders remain porous) or work legally in Bangladesh, and the black market presents one of the few opportunities to earn small sums of money. Some young women unwittingly enter sex trafficking through the false prospect of work as housekeepers or servants, but others enter knowingly, feeling that they have no other choice. The feeling of desperation is especially rampant among the multitude of rape victims who suffer from stigma and shame within this tight-knit Muslim community.

Human trafficking has grown as the severity of the refugee crisis has increased. For decades, limited options for the Rohingya in Myanmar have made them a major target of exploitation and sex trafficking, but the influx of refugees into Bangladesh has greatly expanded the opportunities for criminal enterprises. Hundreds of women and girls have been subjected to forced prostitution not just in Cox’s Bazar and throughout Bangladesh, but across the border in India, Nepal, and Thailand. The women who manage to escape are unable to travel back because they lack citizenship and travel documents.

As increased media coverage and international investigations bring more attention to this issue, fear of abduction among refugees has increased, which has led to negative secondary effects. According to sources working inside the camps, fears of fake police officers looking to snatch young men and women has made many reluctant to engage with the real authorities, even when crime occurs. These fears have also caused some girls and young women to stay within the relative safety of their family homes, missing school for months on end.

The limited capacity of the Bangladeshi civil authorities working in the camps means that some episodes reported by nervous Rohingya women to aid workers and authorities have been mistakenly labelled as trafficking. In one recent case, police officers arresting several youth who had caused a fight in a refugee camp were mistaken by Rohingya witnesses as abductors. In another, a young woman’s family reported her as abducted when she had simply snuck away with her boyfriend for the afternoon.

Refugees desperate for an income have also become targets for the expanding drug running industry. Narcotics smuggling between Myanmar and Bangladesh has long been rampant, but the availability of new potential recruits has greatly expanded the scope and reach of the market. The most widespread drug is Yaba, a methamphetamine-based substance in pill form that is relatively easy to smuggle from northern Myanmar. Drug smugglers entice refugees with relatively high payouts of around $100 per month to traffic drugs between the camps and Cox’s Bazar, where drugs are then shipped throughout the country. As a result, Yaba use has skyrocketed in Bangladesh over the past decade, with a current estimate of five million consumers. According to the Bangladeshi Department of Narcotics Control, this represents a 77-fold increase in usage in just six years. The UN has estimated the number of drug users in Cox’s Bazar to be around 60,000 – about half of the entire metro population. Since August 2017, authorities have seized over 10 million Yaba pills in the camps.

Health concerns

As a result of the mass rapes that the Myanmar military committed in August 2017, the Rohingya camps experienced a baby boom in the summer of 2018. The United Nations estimates that over 25,000 babies were born since May, and experts believe a significant proportion of these births is a result of the mass rapes. It is expected that thousands more will be born before the end of the year.

Because rape victims still face a stigma in this traditional Muslim society, women have experienced social and health care challenges. Many women hide their pregnancies, and the desire for secrecy makes precise birth data difficult to obtain. Around 80 percent of Rohingya women in the camps give birth at home. Abortion is illegal in Bangladesh, but “menstrual regulation” to terminate a pregnancy is allowed and possible for the first 12 weeks. Underground, unsafe abortion is rampant.

Communicable diseases due to poor sanitation and limited resources continue to plague the camps. Because hundreds of thousands of refugees arrived almost overnight, the initial construction of latrines, water pumps, and other facilities was hurried and done in very close quarters. Space is limited for both humans and buildings, with the density of the camps far exceeding UN guidelines. These conditions have enabled the spread of skin and respiratory infections as well as acute diarrhea, with the threat of a malaria outbreak being closely monitored by public health workers.

The strain on the system soon overtook its capacity, with refugees forced to settle outside of the original official boundaries of the established camps, relying on whatever makeshift facilities they could put together quickly. More sustainable and safer infrastructure such as brick and mortar community centers and latrines have only been constructed over the last few months. Monsoon rains, which occur throughout the late summer and early fall months, have hindered much of this hard-fought progress. According to UN High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), about 203,000 people in the largest camps are in need of relocation because of the risk of floods and landslides. Even many long-standing structures such as health centers and schools, which had stood fast for most of the year, have been abandoned as damage from the storms made them untenable. Deforestation because of the need for firewood and building materials has worsened the impact of the weather.

Given the myriad of critical factors threatening the survival of the Rohingya refugees, much relies on the proper use of available resources and effective management. The next installment of this series will examine this topic in depth.

***

Photo by the World Bank Photo Collection via Flickr. All rights reserved by the World Bank.

Shane McCarthy (MPP '17) is a freelance writer and former senior online editor at the Georgetown Public Policy Review.