By this point we’ve all heard about the rising cost of prescription drugs; last month we ran an introduction to this series explaining just that. But what’s the real story behind the trend? Is it simply greedy CEOs hoping to rake in more profits and garner more investor speculation, or is the reality more complicated? A good place to start is by understanding patents and market exclusivity.

Comparing apples and oranges

To many readers out there, patents and market exclusivity in the drug industry might be interpreted as essentially the same thing. Patents provide a twenty-year window free of copy cats, giving drug manufacturers market exclusivity necessary to set prices however they want. This conventional wisdom, as it turns out, isn’t quite in line with the reality.

To demonstrate the difference between patents and market exclusivity, think about Apple and Microsoft operating systems. At a basic level, the two products do many of the same things. Both can be used to draft documents, watch movies, connect to the internet, etc. And while consumers may have particular preferences over which brand they like to use, they still have a choice between which product to buy. Although specific features of these operating systems are protected by patents, neither has market exclusivity to sell operating systems, so Apple can’t sue Microsoft for selling operating systems and vice versa.

Although this is by no means a perfect analog to the pharmaceutical industry, the illustration does demonstrate how property rights from patents and market exclusivity are different. The FDA only acknowledges patents on drugs claiming active ingredients, their composition or formulation, and for how the drug is used. Just because a pharmaceutical company has a patent on a drug doesn’t mean a generic competitor can’t figure out another way to make and then sell what is essentially the same thing.

So what?

If a generic company can find a way to work around a branded drug’s patents and produce an equivalent medicine, they can bring essentially the same medicine to market without expensive clinical trials. This happens routinely in other industries; a good example of this is Lyft entering the market during Uber’s meteoric rise.

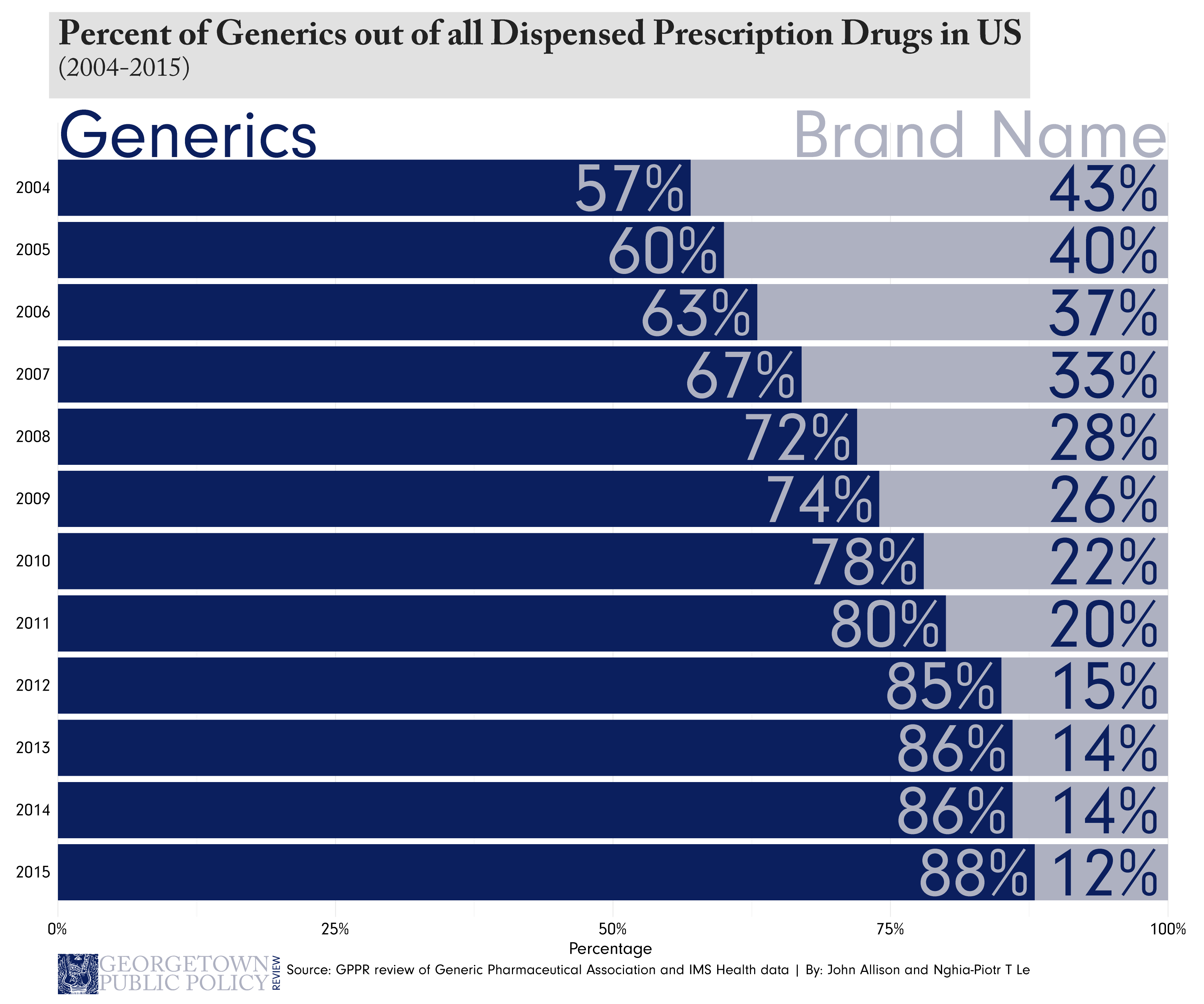

The real consequence to the innovating company is the effect the second mover has on prices. Just as Lyft lowered the prices riders of both Lyft and Uber pay, generic entry into the market affects prices much in the same way. According to the FDA, generic drugs generally cost roughly 80 to 85 percent less than their branded counterparts, meaning the initial inventor often must drop their prices to stay competitive.

A perfect storm

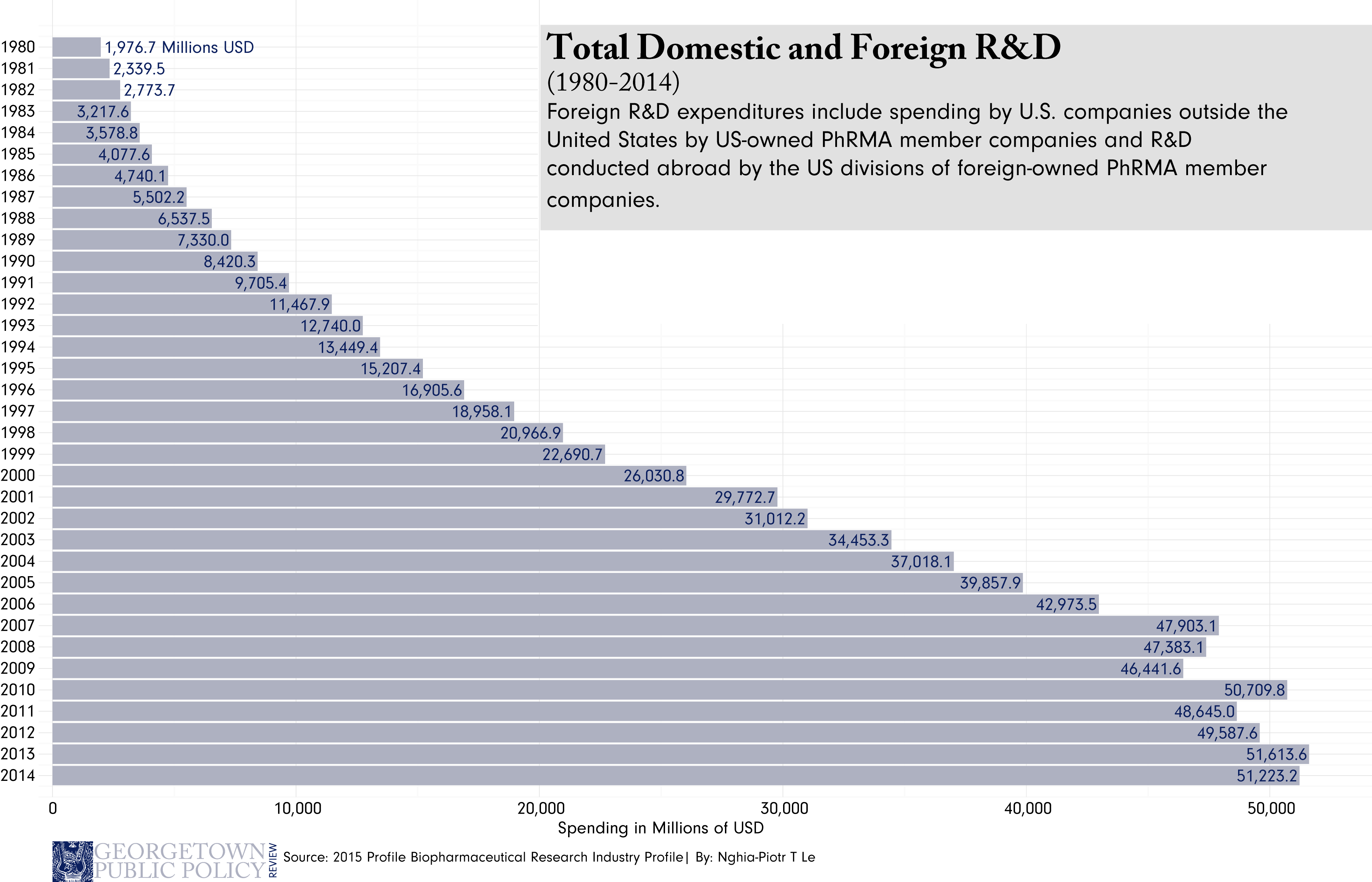

Where the Lift/Uber analogy begins to breakdown, however, is also what makes the pharmaceutical industry unique. For starters, investment in the pharmaceutical industry is an incredibly high-risk, high-reward venture. The costs of bringing drugs to market, though hotly disputed, are recognizably expensive. Clinical trials on drugs that may or may not work costs millions, and without investor confidence may never happen at all.

Another important distinction of the pharmaceutical industry is the products it sells. Unlike Uber or Apple, which admittedly sell products that improve human efficiency and general well-being, pharmaceutical companies sell something more directly valuable – the comprehensive experience of health itself. Whether curing an irritable rash, fighting infection, or curing a previously incurable disease, pharmaceuticals sell something that is necessary to sustain life. So not only is the industry high-risk, high-reward, but the stakes couldn’t be higher. However, for the pharmaceutical industry to keep running expensive trials that create new drugs, there needs to be a sustainable source of investment. As a result, getting investors to bite becomes important, and the failure to do so can become an issue of life and death.

The weapon of choice (or lack thereof)

The heart of this problem is that patents don’t perfectly protect innovator companies from non-innovator competition, theoretically dissuading investment in research and development of new products. Investors want something that will generate return, and generic competition heavily threatens that return. Operating under this reality, the concept of market exclusivity in the pharmaceutical industry begins to sound both distinct and maybe even appealing. By offering not just patent protection, but additional protection on the particular market itself, market exclusivity affords the innovator company a legal monopoly, allowing the innovator to reap massive profits through high prices. By improving the prospects for high-return, investors have more freedom to speculate on the development of drugs.

The Hatch Waxman Act, signed into law in 1984, was in part designed to do just that (we’ll revisit this in more detail later in the series). Under Hatch Waxman, the FDA has the authority to grant exclusive marketing rights after approving the drug. Importantly, the period of exclusivity is in no way related to the patent period, so the two can run concurrently. The length of market exclusivity given to innovators can last from as little as 180-days, to up to seven years depending on the type of drug.

Looking at the bigger picture

In the mainstream discussions of about drug pricing, patents are frequently, and understandably, confused with market exclusivity. The issue, as we’ve noted, is more than a simple misnomer. Understanding the difference between the two provides pivotal background needed to understand policy decisions affecting drug prices. It’s only after understanding why both exist in the first place that we can start to think about the tradeoffs of patent or market protections on prescription drugs.

John Allison is the Senior Policy Focus Editor at the Georgetown Public Policy Review and is a second year MPP student at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. He is a proud native of Kansas where he recently completed his undergraduate degree at Kansas State University. His areas of policy interest include health policy and poverty.