Join Jennifer Lawless, Danny Hayes, and moderator Hannah Bloch from NPR for a continued discussion on Wednesday, 11/18 at the McCourt School for Public Policy. Space limited, so please RSVP here: http://bit.ly/1RpjF5H and send us your questions at #cracktheglass on the event page or Twitter.

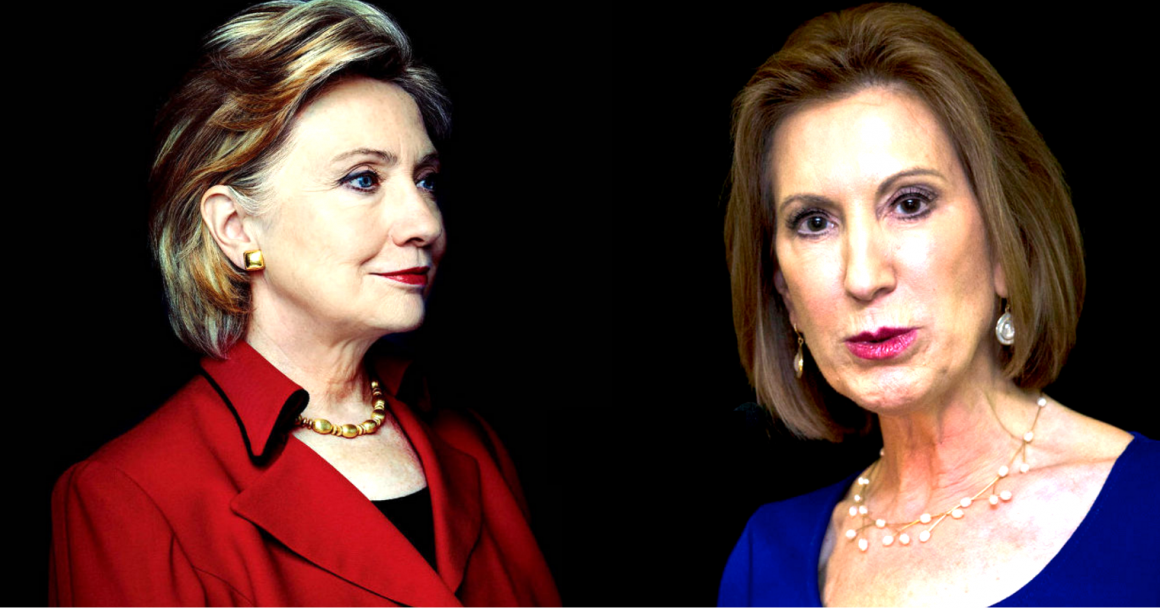

The dawn of another presidential election cycle spurs the, now expected, high-profile match-up between male and female candidates. As Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina both attempt to break the highest glass ceiling to become the first female U.S. president, media outlets confront the ever-present challenge of if and how to neutralize their coverage of female candidates. This begs the question: is the struggle of female candidates and politicians to run for office, win elections, or earn the same legitimacy as their male counterparts compounded by gender-biased media treatment?

New research on this relationship challenges the traditional belief, promoted by politicians, journalists, and pundits themselves, that the campaign environment and the political landscape present more challenges for women. In a new book, Women on the Run: Gender, Media, and Political Campaigns in a Polarized Era, Jennifer Lawless, Director of the Women & Politics Institute at American University, and Danny Hayes, political science professor at George Washington University, offer evidence of the declining difference in media treatment between male and female candidates. They analyzed this relationship based on the suspicion that an increasingly polarized political landscape changed what conventional wisdom and academic research historically suggested about a gendered political media: that media depicts female candidates in a more superficial manner, based on appearance or demonstration of feminine qualities, and voters evaluate them in light of gender stereotypes. They question the assumption, while historically suggested in research, that media portrays female candidates as weaker leaders, less knowledgeable about economic or national security issues, and generally less competent than men. By analyzing patterns of media treatment in the 2010 and 2014 congressional midterm elections, in addition to a survey of approximately 3,000 voters, Lawless and Hayes arrived at a novel conclusion: political partisanship outweighs gender in its discussion in media coverage and impact on voters. Put simply, people care more about political party than gender when evaluating and deciding on candidates.

Political scientist Kathleen Dolan, author of When Does Gender Matter? Women Candidates & Gender Stereotypes in American Elections, recently made the same argument, that gender matters far less to voters than political media and academic research might suggest.[1] Her analysis of two surveys conducted during the 2010 midterm elections, asking voters to evaluate female candidates in House, Senate, and gubernatorial races, suggested that, while voters found men better-suited for politics than women, the same voters were minimally influenced by gender when it came to their assessment of the candidates. Weaving the same thread as Lawless, Dolan argued that voters placed more importance on incumbency, campaign spending, and partisanship. She also found that, although women run for office at lower rates than men, they win the same proportion of races. Other recent studies focusing on non-presidential races corroborate the notion that contemporary political media is not biased in its quality or amount of coverage of female candidates. A 2007 study of six mayoral elections across the U.S. found that the presence of a woman on the ballot actually expanded the range of issues covered in local campaigns in a way that was favorable to female candidate and the strengths voters associated with her.[2]

These new findings confront the traditionally-accepted beliefs about the way gender, and the media’s participation in perpetuating traditional gender roles, might impact voters. Erika Falk’s seminal 2008 book, Women For President, illustrates the history of women in electoral politics over the last 130 years and argues that women receive less coverage from reporters, and suffer from stereotypes that deem them less politically viable, better suited for the vice presidency, and more likely to advocate specifically for special interests rather than nationally salient issues.[3] Her most interesting commentary comes from her critique of the way media tends to frame a woman’s candidacy, particularly by referring to female candidates by their first names, questioning a woman’s readiness for high-profile office, and challenging how her gender would negatively influence her actions, decisions, and interests. With contradictory research now arguing against gender as a primary topic in political media, the question then becomes: does media discriminate in its coverage of female candidates? And if so, how does that impact voters? How does it influence women considering running for office?

__________

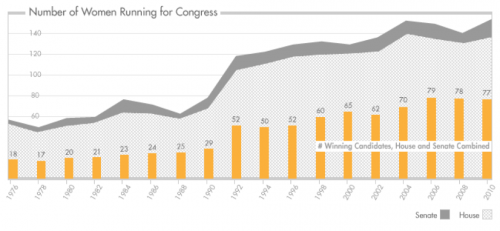

After steady increases in the percentage of female politicians and candidates in the 1980s and 1990s, and stagnated progress in more recent election cycles, the number of women in Congress finally reached triple digits in 2014. The 104 women (out of the 535 total members) in the 114th Congress include Sen. Joni Ernst (R-IA), the first woman elected from Iowa and the first female veteran to serve in the U.S. Senate, Sen. Shelley Moore Capito (R-WV), the first female senator from West Virginia, and Rep. Mia Love (R-UT), the first African-American Republican woman elected from Utah.[4] This illusion of progress, however, suffers from a myriad of other statistics. Women comprise only 20 percent of the U.S. Senate, 24.3 percent of seats in state legislatures and 12 percent of state governors.[5] Worse, women of color, a group that receives noticeably less attention in the women’s movement, make up only 6.2 percent of Congress, 4 percent of governors and 5.2 percent of state legislatures.[6] In the media-friendly, ‘Where America Ranks’ game, the U.S. places 83rd of 137 included countries for representation of women in parliament, in the similar ranks of countries such as Kenya, Indonesia, and the United Arab Emirates.[7] If women represent approximately half of the U.S. population, what drives their vast underrepresentation in politics?

Part of this gap grounds itself in the arguable presence and power of a gendered media lens, which, when covering female politicians or candidates, highlights their incompetencies, appearance, marital status, superficial or feminized traits, and ability to fulfill traditional gender roles more frequently or harshly than their male counterparts.[8] Seminal research by Kim Fridkin Kahn in 1994 found that, from an analysis of 47 statewide campaigns between 1982 and 1988, both female Senate and gubernatorial candidates received less coverage than men, and the coverage they did receive was more likely to be focused on “female” issues.[9] Academics also highlight the danger of media coverage that focuses on ‘feminine’ political issues, such as health care and education, arguing that this perpetuates an existing gender bias that women cannot address more ‘masculine’ issues, such as terrorism, national security, or the economy.[10] In 2004, Lawless published an article, Women, War, and Winning Elections: Gender Stereotyping in the Post-September 11th Era, that built on the body of literature about the types of issues voters associate with male and female candidates. Survey results showed that “war on terror” vernacular and relevance in current events afforded a positive bias toward male candidates. Lawless also noted when the issue of terrorism was salient, women candidates suffered, an outcome grounded in the finding that individuals who favored more aggressive counterterrorism policies were more likely to support male candidates.[11]

Research of this candidate bias also highlights the salient influence media has over the nature of information that reaches voters. A 2001 study on national newspaper coverage during Elizabeth Dole’s 2000 presidential campaign found that, despite her rich political career, she received substantively different press than her male counterparts: coverage focused more on her personal traits than on issues, and directly quoted her at a lower rate compared to her male running mates. The authors interestingly concluded that this difference was due to stories written by male reporters.[12] Academics suggest this might stem from the ‘novelty effect’, which theorizes that when traditional or societal norms are violated, such as a female running for high-powered office, media outlets respond by covering said candidates less or in a more negative light than their male counterparts.[13] While less empirically studied, the impact of this bias risks negatively influencing voters, particularly those that carry their own gender biases, and further lowering females’ political ambition compared to men, a trend already evidenced in social science research.[14] One study found that positive media cues, given to both those with and without sexist attitudes, led to consistently positive views of a female senator, while negative media cues led to hostile views of the same senator, specifically amongst those with some existing sexist attitude toward women.[15] Research on gender-biased political media, while evidencing its existence, questions the extent to which it might distort voters’ evaluations of female candidates. More, academics wonder how media bias might discourage women from running for political office or hinder the success of women in elections.

In an interview with GPPR, Lawless and Hayes argue that the view that women have a harder time winning elections due to media bias is outdated: “the [twenty-first] century political landscape is far more equitable than it’s often portrayed to be.” They justify the theory of a more even electoral playing field in two features of modern American politics: the declining novelty of female politicians and increasingly polarized political parties. Following the logic of the ‘novelty effect’, the less radical the idea of a woman in power, the more the media will cover women in these positions. Increased polarization suggests that politically-aligned male and female candidates diverge less in their issue campaigns, such that media begins to cover them similarly and voters have less impetus upon which to evaluate them differently. By analyzing hundreds of U.S. House races from the 2010 and 2014 midterm elections, involving more than 1,500 candidates, 400,000 campaign ads, and 50,000 social media messages, Lawless and Hayes’ new research confirmed that men and women run almost identical campaigns, “from the issues they talk about to the language they use to the personal traits they tell voters they possess.” The campaigns also align in the scope of their media coverage – their analysis of over 10,000 local newspaper articles showed that male and female candidates received relatively the same amount and substance of coverage. Female candidates suffered no more than men when it came to the media’s focus on their appearance, ability to conform to their gender role, or stance on gender-specific issues.

How might this depiction of media continue to impact the presence, or lack thereof, of women in politics? Lawless argues that the concern about media and voter bias should be less about its impact on keeping women out of office, and more about suppressing women’s desire to run in the first place. Past research by Lawless has focused on the enduring gender gap in political ambition. A 2011 study by Lawless and Richard Fox found that 45 percent of surveyed women had considered running for office, compared to 62 percent of men – the same 16 percentage point gap, albeit at lower percentages, that existed in 2001.[16] When considering family constraints, 70 percent of men with children under 7 considered running for office compared to only 49 percent of women, a number that changed minimally when considering women without children. The drivers of low levels of female political ambition are multi-dimensional. Lawless and Fox highlighted seven factors that make this “decision calculus” far more complex for women than men, including the difficulty of past female candidates in the electoral arena, larger shares of household and childcare responsibilities falling to women, less encouragement for women to run, lower levels of competitiveness and confidence in females considering running compared to men, and women’s preconceptions that the electoral environment is competitive and biased against women.[17]

Given the evidence, one could make a strong case that this preconception is correct, that the seemingly biased amount or nature of media coverage of female politicians plays a role in alienating women from the process. A 2006 study found that more female candidates visible in media, such as those in national news or running for high-profile office, resulted in more women running for office. Supporting Lawless’ own research that women struggle to consider running for office in the first place, this finding suggests that, at a minimum, the amount of coverage female candidates receive can impact the number of women who can envision a likely path for themselves.[18] However Lawless and Hayes don’t believe that media and voters hold women back in this domain. “These views are driven in part by the belief that the political arena is rife with sexism and discrimination,” they stated in their interview, an outdated argument that compounds the notion that women also need to feel more qualified and more prepared than their male competitors to reach similar levels of success.

Lawless and Hayes make a point to differentiate between the majority of female candidates and more high-profile ones, most recently Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina. They highlighted that the trajectory of these women fail to represent what the typical female candidate will experience if she runs for office: “Congressional races and the hundreds of thousands of down-ballot contests just like them are generally low-information affairs. There’s little reason to think that candidates’ experiences in those contests will be like what they encounter when they seek national or statewide office.” Related research also supports that the extent to which media coverage suffers from a gender bias increases up the political ladder: the higher the office sought by a female candidate, the more gendered the media coverage.[19]

When asked about the current presidential election cycle, and how it relates to their most recent body of evidence, Lawless and Hayes reiterated that the biased media content people reference when considering high-profile female candidates represents an anomaly compared to the coverage the average female candidate receives. “There is likely a widespread belief that much of Clinton’s coverage is about her clothes – the pantsuit problem, we might call it. But it’s important to keep in mind that the vast majority of her coverage has been about other things: her status as the Democratic front-runner, whether Bernie Sanders is pushing her to the left, Benghazi, the email server, and so forth. In other words, the denominator is critical.”

Their primary message? Society might be unnecessarily holding on to the belief that the media holds female candidates and politicians to higher and tougher standards, and thus derails their likelihoods of success. More, continued expectations of gender roles and contemporary criticism of feminism and high-powered females may not constrain women in the political arena as much as past research suggests.

Neither Lawless nor Hayes deny the unmistakable role of gender as a consistent theme in media coverage, particularly during presidential elections. In their interview, they cite the novelty of the first potential female president to be “newsworthy”, as both Hillary Clinton and Carly Fiorina “have a chance to crack that highest glass ceiling.” They also differentiate  the presidential election cycle from less high-profile races, pointing out that both candidates strategically draw attention to their gender when it’s politically advantageous and on a national scale. Clinton regularly reminds voters that she is a grandmother, made a reference to women’s longer trips to the bathroom in the most recent Democratic debate, and called herself more of an “outsider” than any candidate given her attempt to be the first female president. In response to Donald Trump’s commentary about her appearance, Fiorina produced a response ad that highlighted her gender as a crucial part of her campaign and why voters should support her. These examples validate yet another argument present in Lawless and Hayes’ findings: that media coverage focuses on gender when gender is a novel part of the story, such as a woman running for president, or when candidates purposefully insert it into the conversation.

the presidential election cycle from less high-profile races, pointing out that both candidates strategically draw attention to their gender when it’s politically advantageous and on a national scale. Clinton regularly reminds voters that she is a grandmother, made a reference to women’s longer trips to the bathroom in the most recent Democratic debate, and called herself more of an “outsider” than any candidate given her attempt to be the first female president. In response to Donald Trump’s commentary about her appearance, Fiorina produced a response ad that highlighted her gender as a crucial part of her campaign and why voters should support her. These examples validate yet another argument present in Lawless and Hayes’ findings: that media coverage focuses on gender when gender is a novel part of the story, such as a woman running for president, or when candidates purposefully insert it into the conversation.

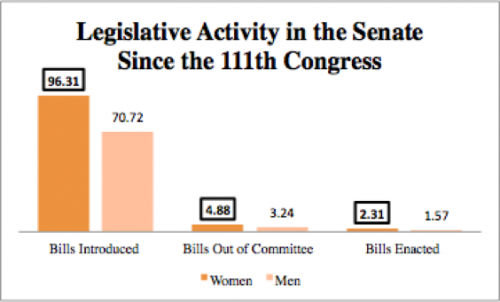

Both authors ground the importance of their research in its ability to inform those that play an active role in the candidate recruiting process, such as party leaders, politicians, donors, activists, and nonprofits, calling on them to recognize and promote that female candidates will likely face no more difficulty on the campaign trail than men. In their interview, they also connect their findings to future success for female candidates and women’s policy issues: “Electing more women is one way to ensure that politicians address a diverse array of policy concerns. Women who replace men in the same district are more likely to focus on “women’s issues,” such as child care, reproductive rights, pay equity, and poverty.” They cite a body of evidence that suggests that female politicians from both sides of the aisle are more likely than men to use bill sponsorship and co-sponsorship to promote women’s policy issues, introduce bills related to civil rights and liberties, health, and labor, and work across the aisle to introduce and effectively pass legislation.[20]

While their new research highlights partisanship over gender as the more influential factor in shaping voter opinions and outcomes, Lawless and Hayes don’t shy away from recognizing the dire need for gender diversity in political office: “If women do not run for office, at least in part because of a widespread belief that the campaign environment would be biased against them, then that threatens the legitimacy of both public policy and the larger democratic process.”

______

Jennifer L. Lawless is the Director of the Women and Politics Institute at American Univeristy and a professor at the School of Public Affairs. She received her M.A. and Ph.D. in political science from Stanford University, and is a nationally recognized expert on women and politics. She is the author of Running from Office: Why Young Americans Are Turned Off to Politics (with Richard L. Fox), Becoming a Candidate: Political Ambition and the Decision to Run for Office, and It Still Takes a Candidate: Why Women Don’t Run for Office (with Richard L. Fox).

Danny Hayes is an associate professor of political science at George Washington University. He received his Ph.D. from the University of Texas at Austin, and his research focuses on how information from the media and other political actors influences the public. He is the co-author of Influence from Abroad: Foreign Voices, the Media, and U.S. Public Opinion and his work has appeared in the American Journal of Political Science, Journal of Politics,Political Behavior, Political Communication, and Politics & Gender, among other outlets.

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

[1] Dolan, Kathleen. 2014. “When Does Gender Matter? Women Candidates & Gender Stereotypes in American Elections.” Oxford University Press.

[2] Atkeson, L. R., & Krebs, T. B. 2007. Press coverage of mayoral candidates: The role of gender in news reporting and campaign issue speech. Political Research Quarterly

[3] Falk, Erika. 2008. “Women for President: Media Bias in Eight Campaigns.” Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

[4] Center for American Women and Politics. 2014. “2014: Not a Landmark Year for Women, Despite Some Notable Firsts.” Available at http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/resources/pressrelease_11-05-14-electionresults.pdf; Abramson, Alana. 2014. “Election 2014” How Female Candidates Fared in the Midterms.” ABC News. Available at: http://abcnews.go.com/Politics/election-2014-record-breaking-number-women-serve-congress/story?id=26716664

[5] Center for American Women and Politics. 2014.

[6] Center for American Women and Politics. 2015. “Women in Elective Office in 2015.” Available at http://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/women-elective-office-2015

[7] World Economic Forum. 2014. “The Global Gender Gap Report.” World Economic Forum.

[8] Fowler, Linda and Jennifer Lawless. 2009. “Looking for Sex in All the Wrong Places: Press Coverage and the Electoral Fortunes of Gubernatorial Candidates.” Perspectives on Politics 7: 519-536.

[9] Kahn, K. F. 1994. “The distorted mirror: Press coverage of women candidates for statewide office.” The Journal of Politics, 56(01), 154-173; Kahn, K. F. 1994. “Does gender make a difference? An experimental examination of sex stereotypes and press patterns in statewide campaigns.” American Journal of Political Science, 162-195.

[10] Khan, Kim Fridkin. 1994. “The Distorted Mirror: Press Coverage of Women Candidates for Statewide Office.” In Gendering American Politics: Perspectives from the Literature. New York: Pearson Longman, 203-218. ; Falk, Erica and Kate Kelski. 2006. “Issue Saliency and Gender Stereotypes: Support for Women as Presidents in Times of War and Terrorism.” Social Science Quarterly 87 (1): 1-18.

[11] Lawless, Jennifer. 2004. “Women, War, and Winning Elections: Gender Stereotyping in the Post-September 11th Era.” Political Research Quarterly 57 (3):479-90.

[12] Aday, S., & Devitt, J. (2001). Style over substance: Newspaper coverage of Elizabeth Dole’s presidential bid. The Harvard International Journal of Press/Politics, 6(2), 52-73.

[13] Fowler and Lawless. 2009.; Mills, Sara and Louise Mullaney. (2001). Language, Gender and Feminism: Theory, Methodology and Practice. New York: Routledge, 144-60.

[14] Lawless, Jennifer and Richard Fox. 2008. “Why Are Women Still Not Running for Public Office?” Issues in Governance Studies. Brookings Institution.

[15] Schlehofer, Michele, Bettina J. Casad, Michelle C. Bligh, and Angela R. Grotto. 2011. “Navigating Public Prejudices: The Impact of Media and Attitudes on High-Profile Female Political Leaders.” Journal of Sex Roles 65: 69-82.

[16] Lawless, Jennifer, and Richard Fox. 2012. “Men Rule: The Continued Under-representation of Women in U.S. Politics.” Women and Politics Institute, American University.

[17] Lawless, Jennifer, and Richard Fox. 2012.

[18] Campbell, David and Christina Wolbrecht. 2006. “See Jane Run: Women Politicians as Role Models for Adolescents.” The Journal for Politics 2: 233-247.

[19] Meeks, Lindsey. 2012. “Is She ‘Man Enough’? Women Candidates, Executive Political Offices, and News Coverage.” Journal of Communication (62): 175-93; Kittilson, Miki Caul, and Kim Fridkin. 2008. “Gender, candidate portrayals and election campaigns: A comparative perspective.” Politics & Gender 4(3): 371-392.

[20] Thomas, Sue. (2009). “The Impact of Women on State Legislative Policies.” The Journal of Politics 53(4): 958-976; Volden, Craig, and Alan Wiseman. (2014). The Legislative Effectiveness of Women in Congress. Cambridge University Press; Klein, Mariel. (2015). “Working Together and Across the Aisle, Female Senators Pass More Legislation Than Male Colleagues.” Quorum. Available at https://www.quorum.us/blog/women-work-together-pass-more-legislation/.

2 thoughts on “Media’s War on Women in Politics? How New Research Is Challenging Traditional Beliefs”

Comments are closed.