Introduction

As the world continues to advance technologically, more and more jobs become susceptible to automation, with machines completing tasks formerly undertaken by people on an increasing scale. Automation is widely hailed as a cost-effective, efficiency-oriented solution for businesses, which can use technology to greatly reduce instances of human error in their work, speed up production, and cut long-term costs. As automation has grown, a debate about its implications for the future of work has emerged too.

The debate on automation

The automation debate generally centers around the extent to which automation will affect workers in the future. Among economists, there is a general consensus that automation is a key contributing factor to societal inequality, with associated job loss outweighing any negative externalities to workers from trade or immigration. These economists argue automation will lead to mass job losses in the coming decades and, while new jobs will certainly be created, the rate at which they are created will not be sufficient to offset the losses caused by automation.

The more repetitive the tasks associated with a particular job, the easier those tasks are to map and replicate with technology.

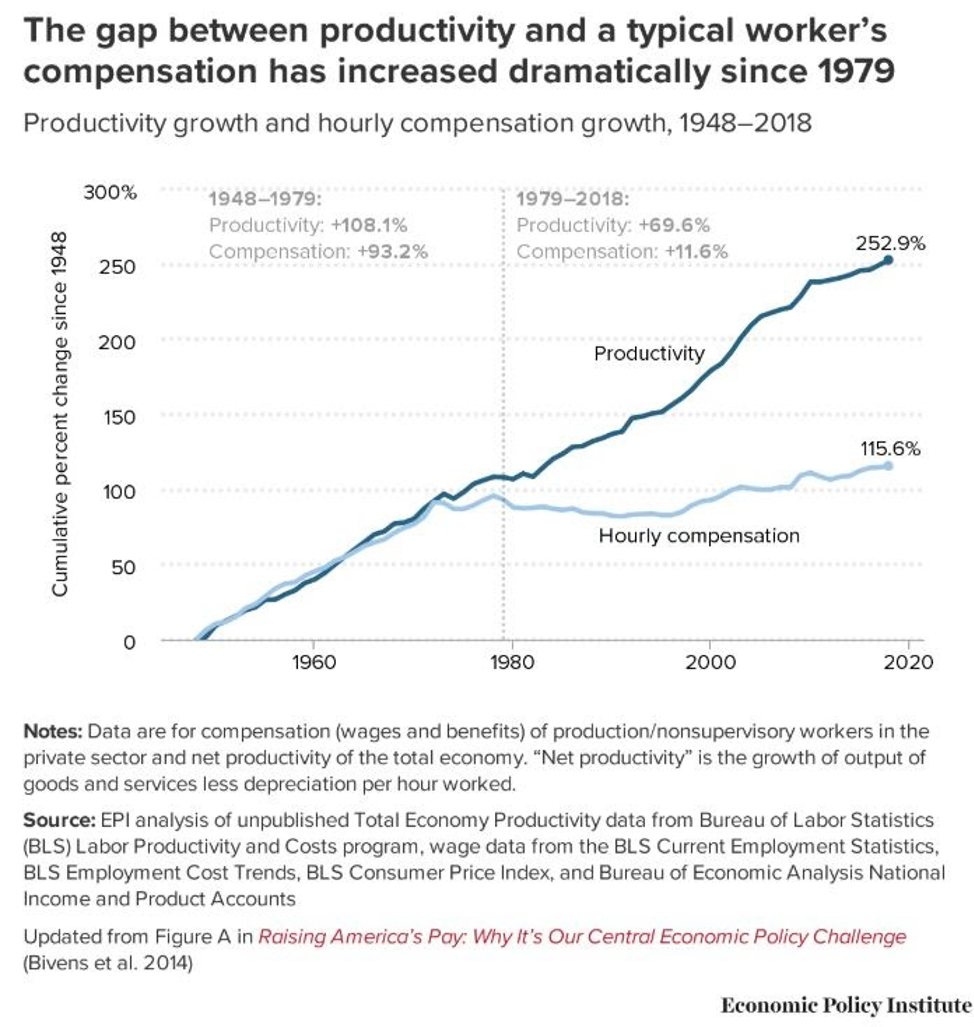

This statement rings true for a wide range of jobs, whether traditionally blue collar or white collar, including factory, assistant or secretarial, and even legal and financial work. The jobs safest from automation are managerial or executive positions. Hence, economists claim, the jobs most susceptible to automation are those predominantly held by members of the lower and middle classes, whereas the wealthiest members of society hold the safest jobs. Research from the Economic Policy Institute supports these claims; though worker productivity is on the rise due to automation, wages have stagnated.

Echoing economists’ assertions, those working in the technology or tech-adjacent industries are well aware of the power automation wields. A recent report by the research firm Forrester estimates that over 1 million knowledge-work jobs — jobs that require working with information rather than performing manual labor — will be lost in 2020. However, the report also estimates that 331,500 net human-touch jobs requiring intuition, empathy and physical and mental agility will be added to the US workforce this year. Thus, industry experts claim jobs requiring creative thinking, adaptability and human emotion will be more highly valued. While there will always be a sufficient volume of jobs available to the public, the jobs of the future will look different from those available today. As such, a significant portion of workers will require training in new skills.

Within academia, scholars appear split on the implications of automation for workers. Existing scholarly literature on the topic generally falls into one of three camps: optimistic, pessimistic, and somewhere in between. Optimists envision a future in which existing work will either be abolished at no cost to workers due to (universal) basic income programs or supported by new technologies which will allow humans to work even more productively.

Pessimists, on the other hand argue that, while society is headed toward a post-work future, with large swaths of existing human jobs becoming obsolete, there is no indication that workers will be protected. They point to a rise in offshoring and the existence of large, exploitative organizations that provide poor wages, working conditions, and benefits to many of their workers.

Scholars between the optimists and pessimists argue that their peers’ analyses are gross oversimplifications of the issue at hand. They acknowledge automation is an important issue for society, researchers should continue to study its projected impact, and policy leaders should take action to ensure future job security for workers. However, they reject that automation will have a completely transformative effect on the economy.

Finally, politicians appear divided on the issue of automation and its impacts, and not just along party lines. Due to Andrew Yang’s 2020 presidential campaign, the issue has garnered some additional attention this election cycle. Yang has made the issue a cornerstone of his campaign, arguing that the United States must stop denying the effects of automation and implement 21st-century solutions such as universal basic income to address these effects.

In contrast, Senator Elizabeth Warren, argues the idea of automation causing job insecurity is “a good story, except it’s not really true.” Warren, instead, points to harmful trade policy as the main culprit behind American job insecurity. Other 2020 Democratic candidates fall on a spectrum between Yang and Warren with regard to their stances on automation and the future of work, with Pete Buttigieg emphasizing the importance of education programs in the face of increased automation and Senator Bernie Sanders proposing guaranteeing federal jobs for workers displaced at the hands of automation.

Takeaways from the debate on automation

The sheer variety of voices in the loud and lively debate regarding the impact of automation on the future of work makes identifying the problem, developing a robust understanding of the problem and formulating an appropriate response difficult. Furthermore, there is a lack of forward-looking data, meaning predictive models are built using past trends. Since researchers cannot predict the future, they must rely on existing political theories, models, and anecdotal evidence to formulate their arguments. Many studies thus end up either overly broad or narrow in focus, often lacking evidence-based approaches. For instance, much of the existing literary works on automation and the future of work display inherent political bias on the part of their authors, as evidenced by their overt optimistic, pessimistic or neutral undertones.

On the other hand, economists’ assertions, while evidence-based, rely on general productivity and growth models, failing to zero in on the effects of technology in the workplace specifically. Proving causation between technological advancement and job security using these models is difficult due to the number of potential confounding variables, such as trade, that could exist. Industry specialists have the opposite problem: while it is easier to demonstrate the impact of technology through industry practices by working directly with organizations to conduct studies, the conclusions drawn from these studies often lack external validity due to their relatively narrow approach, which is heavily reliant on the particular clients with which they work, and therefore cannot be easily generalized.

Finally, most politicians’ lack of academic or industry experience relating to automation precludes them from convincingly articulating what it means for the future of work. Nevertheless, politicians have campaigns to run and in the absence of a general consensus on the impact of automation on job security can point to various studies and assertions to spin existing information in their favor. Until a new, evidence-based method for evaluating the relationship between automation and the future of work is introduced to the automation-job security debate, existing stakeholders will continue to talk in circles. The problem is in the event that automation does progress enough to the point where tangible, associated job loss occurs, it may be too late to take key preventative policy actions in the future, due to the exponential nature of technological development.

Where do we go from here?

The effect of automation on the future of work is notoriously difficult to study, due to the various angles taken by those examining this relationship and the lack of data regarding the ever-evolving prevalence of technology in the workplace. The best way to remedy the extant information gap, which, if filled, would allow for more robust analysis of the relationship between automation and workforce development, is to examine the relationship by designing real-time experiments. One researcher, Benjamin Shestakofsky, designed such an experiment: a 19-month long study at a software firm to test how relations between workers and technology evolved over three phases of the company’s development. The results of the study showed that despite increasingly automating its own processes, the firm opted not to perfect its software algorithms to continuously push people out of the production process and instead continually reorganized to allow humans to work with the software. The study suggests that automation is not necessarily detrimental to workers. In order to better understand the aggregate effects of automation on the workforce, studies like Shestakofsky’s need to be replicated on a larger scale and a longer-term basis, controlling for factors such as regional differences, company culture, and so forth. Doing so will allow researchers to reach causal inferences/conclusions and translate them into meaningful conclusions about what automation means for the future of work.

Cover picture source: Mixabest | Wikimedia Commons

Originally from Germany, Hannah moved to Boston when she was young. After growing up in New England, she attended American University in Washington, DC, where she majored in International Relations and minored in Economics, French and Spanish. She also earned two translation certificates in French and Spanish. Upon graduating from American University, Hannah moved to London, where she worked for a financial technology start-up. After two years, she transferred to New York, where she took over operations for her employer's North American clients. At McCourt, Hannah is focusing primarily on technology policy. She is interested in studying economic shifts due to technological advancement and sees herself going into think thank work after McCourt. In her spare time, Hannah likes to read, spend time outdoors and explore different corners of DC.

2 thoughts on “Reevaluating the Conversation on Automation and the Future of Work”

Comments are closed.