By Kristine Johnston

In a previous article I discussed the monetary and non-monetary costs and benefits of Capital Bikeshare, and how more research is needed to fully understand the economic, health, and environmental impacts of the bikeshare system. However, even without detailed evidence, Capital Bikeshare has been largely hailed as a success, and continues to grow and attract more riders each year.

Despite all of Capital Bikeshare’s success, there seems to be one area in which it is not meeting expectations: reaching low-income neighborhoods and residents. Take a minute to think about the average Capital Bikeshare user. Most likely you think of someone in a suit or dress on his or her way to work, a young professional stopping at Whole Foods to buy groceries, or a family of tourists sightseeing on the Mall. You probably do not think ofa blue-collar worker replacing her bus trip to work with a bike ride, or a kid in Anacostia going to meet up with his friends.

Yet, the Federal Highway Administration’s guide to bikeshare implementation lists “the program’s ability to provide connections for underserved communities” as one key metric for evaluating a bikeshare program’s success. In line with the FHA’s guidance, most bikeshare programs cite increased access and mobility for underprivileged residents as a key objective and have primarily focused on achieving it through the expansion of the network to low-income areas and the removal of financial barriers.

A recent Washington Post article highlighted the outreach initiatives Capital Bikeshare has in place and the challenges it faces in reaching all sectors of DC’s population. These challenges include language barriers, lack of money or credit among low-income residents, and limited interest in some neighborhoods. The article focuses on new efforts being made to increase ridership among non-white demographics, including publishing brochures in both English and Spanish, advertising on buses, and having staff educate residents on how Capital Bikeshare works.

However, what this and other similar articles fail to discuss is why other previous efforts have had limited success in increasing access among low-income and minority demographics.

The Problem Visualized

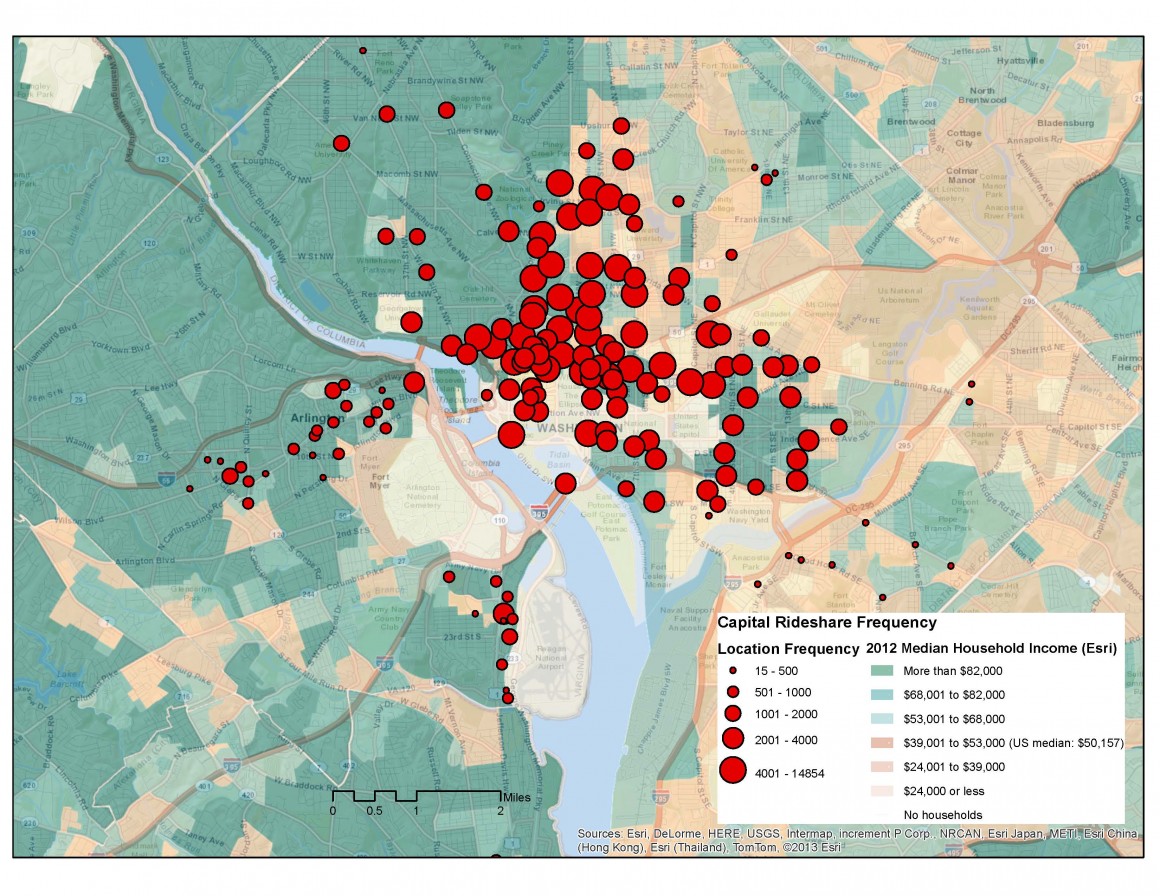

The map below shows the placement of Capital Bikeshare stations (taken from ArcGIS data from March 2013) overlaid on a map of neighborhood average household income, with the size of the bubbles indicating the number of trips in the last quarter of 2013.

There are a couple of interesting observations to be made from this visual. First, the map clearly shows that stations are clustered in the wealthy areas of DC’s downtown and along the Metro’s Orange line in Arlington, while they are few and far between in Wards 7 and 8 south of the Anacostia River and in the northeast neighborhoods of the District – areas that are historically low-income. While some areas of the city are exceptions – the Glover Park area north of Georgetown, for example, is wealthy but has very few stations – and while there are certainly many contributing factors to station placement within a city, the general trend from the map is a high density of stations in wealthier areas and a low density in lower income areas.

There are a couple of interesting observations to be made from this visual. First, the map clearly shows that stations are clustered in the wealthy areas of DC’s downtown and along the Metro’s Orange line in Arlington, while they are few and far between in Wards 7 and 8 south of the Anacostia River and in the northeast neighborhoods of the District – areas that are historically low-income. While some areas of the city are exceptions – the Glover Park area north of Georgetown, for example, is wealthy but has very few stations – and while there are certainly many contributing factors to station placement within a city, the general trend from the map is a high density of stations in wealthier areas and a low density in lower income areas.

The data from Capital Bikeshare’s survey results show that ridership reflects this trend: Only 8 percent of Capital Bikeshare members have a household income below $35,000, while 45 percent live in households that earn more than $100,000. This compares to about 30 percent of the population in the District whose household annual income is less than $35,000, according to the 2012 American Community Survey. 95 percent of Capital Bikeshare members who responded to the survey were employed, compared to about 70 percent in the Washington metro area, as estimated by the US Census Bureau. Only 3.5 percent of Capital Bikeshare members are African American, a group that comprises 25.8 percent of the population in the greater Washington, DC area.

One step that Capital Bikeshare has taken to address the inequalities in program participation is to install more stations in low-income areas. For example, Arlington County recently added stations to the South Arlington/Columbia Pike area, which is less affluent than the communities along the Metro’s Orange and Blue Lines, where Arlington’s stations had previously been concentrated. . As Bike Arlington’s Chris Eatough explained in an email exchange, “It might take a bit longer and require more outreach for the ridership [away from the Metro corridors] to really shine, but we are committed to this and feel it’s important to bring bikeshare to more people in Arlington.”

However, making sure stations are spread out across the city is not enough. The second important piece of information that the map reveals is that stations in low-income neighborhoods report very low usage levels compared to those in wealthier areas of the city. This may be because these areas are farther from the denser, more commercial areas in the center of the city –or because the scarcity of stations in these neighborhoods makes bikeshare less appealing, since there are fewer route options. These hypotheses are consistent with analyses of ridership and station location that have shown that ridership increases at stations closer to the network center and at stations with more surrounding stations within three miles.

The Institute for Transportation and Development Policy’s Bike-Share Planning Guide recommends 10-16 stations per kilometer squared, far more than what is currently in place in these low-income areas. In Washington, DC, however, station density and proximity to the city center do not fully explain the situation. The map also shows that stations in Northwest DC are distant from downtown DC and are few and far between and yet display much greater ridership than those similarly sparse and remote stations in DC’s low-income areas.

Another frequently cited explanation for low usage is that residents in these areas may not able to afford a membership or may not have a credit card, which is necessary to enroll. In an effort to make the system more affordable, Capital Bikeshare partnered with Bank On DC to provide a discounted annual rate ($50) to low-income customers, and to provide access to those who do not have a credit card. Capital Bikeshare has also partnered with Back on My Feet to provide free memberships to homeless people. While these are important programs, they are not enough to make the stations in Anacostia come anywhere near the same ridership levels as the stations in areas like Dupont Circle. The gap between Dupont Circle’s almost 15,000 rides in the 4th quarter of 2013 and Southeast DC Congress Heights Metro’s 50 rides in that same period is evidence of the magnitude of the difference.

The Components of a Bicycling Culture

With the limited success of infrastructure planning and financial incentives, planners are increasingly recognizing the culturalaspect that drives demand for and use of bikeshare programs. Though, Bikeshare can help foster a culture of biking, there has to be some minimum level of interest already in place in order for it to really take hold because people are more likely to consider cycling when they regularly see those around them doing the same. For various reasons, cycling just may not be popular among certain demographic groups, regardless of whether or not they face economic barriers. And this would make traditional methods for increasing use of bikeshare programs ineffective.

If we think of culture as a way of life, then the presence of a cycling culture is largely a product of a community’s environment.

Safety concerns, a lack of cycling infrastructure, low levels of health and fitness in the population, and a popular perception that bikes are for the working class, while car ownership is a sign of wealth, are all major obstacles that feed into a mentality that bicycling is not practical or desirable as a daily mode of transportation.

The small body of literature on bicycling among different demographic and economic groups sheds some light on which obstacles to a cycling culture are present in low-income and minority areas. A study from the Sierra Club and the League of American Bicyclists cites that African Americans, Hispanics, and Asian Americans combined make only 23 percent of the total bike trips in the US. In comparison, these groups make up about 35.6 percent of the US population. Furthermore, fatality rates for Hispanics and African Americans are 26 percent and 30 percent higher, respectively, than for white bicyclists, largely due to a lack of bicycling infrastructure in predominantly Hispanic or African American neighborhoods.

A survey conducted by the Atlantic’s Citylab found that commuters in poor urban Washington, DC ranked cycling and bikesharing among the bottom three preferred modes of commuting, out of a list of nine. Chief among their concerns were poor road safety and infrastructure. If people are afraid to ride a bike in their neighborhood, then no amount of publicity or financial assistance will induce them to participate in bike sharing. So, a first step before installing a bikeshare station may be to improve bike lanes and, where possible, install protected bike lanes. A Portland University study found that on streets with new protected bike lanes, ridership increased from 21-171 percent, and 10 percent of riders had switched to cycling from other forms of transportation. Unfortunately, protected bike lanes are more likely to be installed on routes that already have large numbers of cyclists, and it may be hard to gain the political will necessary to invest in areas with currently low ridership.

Interestingly, in the CityLab study, two of the other stated reasons for ranking cycling so low were physical exertion and poor health or disability. Research has shown that low-income areas tend to have higher obesity rates, due to multiple factors such as lack of financial resources, limited access to healthy foods, and few recreational facilities. In the same way that bikeshare can grow the bicycling culture if there is already some interest, so too can bikeshare improve community health, but only if riders have a base level of fitness to be able to (and to want to) ride the bikes.

The data reflects this: A George Washington University study on the health benefits and characteristics of Capital Bikeshare members found that 49.7 percent of members reporting being in very good health, and 16.1 percent in excellent health, while 90 percent reported getting at least one hour of moderate to strenuous exercise per week outside of their Capital Bikeshare use. Only about 7 percent reported being in fair or poor health. Obviously these indicators are self-reported, and, as I mention in my previous article, those who responded to the survey are more likely to be frequent (more active) users of Capital Bikeshare. Still, it gives some indication that people who use Capital Bikeshare are generally active and in good health. The report’s authors suggest instituting health-related grants or funding from health insurance companies in order to promote bikeshare as a healthy lifestyle choice for low-income residents.

Another innovative solution is being implemented in Boston, where doctors can “Prescribe-a-Bike,” allowing patients to purchase a year-long membership to Hubway for only $5. So far, 900 people have taken advantage of the discount, indicating that the right incentives can induce people to join bikeshare who may not have considered it otherwise.

This brief look at the research suggests among some low-income and minority groups there is a demand for bicycling as a mode of increased access and mobility, but that there are major systemic barriers beyond affordability and access to stations that are preventing bicycling from becoming a main form of transportation in those areas.

Assuming that people want and will use Capital Bikeshare if only they have a credit card and station nearby misses the many nuanced barriers to use and restricts creative thinking about other ways to make the system work well for low-income residents. If the issue is safety, the city should make a concerted effort to install bike lanes between the dispersed stations in these low-income areas. If the issue is health, marketing should be integrated with a larger health campaign that promotes Capital Bikeshare as an accessible and manageable tool for increasing fitness levels. And if bikes are seen as inferior to cars, bikeshare should not be advertised as a replacement to driving, but as a fun, healthy recreational activity. Where just the sight of shiny red bikes is not enough to induce people to ride, other actions will have to occur first to create an environment and culture receptive to bike sharing.

So how do we really know which alternative actions will be most effective? The first step, also suggested by the GW study, is to figure out the exact barriers to use, which will likely vary by city and even neighborhood. If Capital Bikeshare can conduct large-scale surveys of actual users, why not do the same for low-income “target” communities? Let’s just ask these populations if they would like to use Capital Bikeshare, and if not, why not? Until then, we may just be spinning our wheels.

Kristine Johnston is a Research Analyst at Mathematica Policy Research and a recent graduate of the Master of International Development Policy program at MSPP. Prior to attending MSPP, Kristine worked with Project Muso Ladamunen in Mali and with Social Impact in Washington, DC. Her research interests include international development, impact evaluation, education, infrastructure development, urban planning, and bike sharing.

Why does your title say that no one is asking this question, when that’s demonstrably not true?

Geoffrey – “The question no one is asking” is not whether or not bikeshare is reaching low-income communities, but rather if culture is a reason why it isn’t. My impression is that few people have really looked closely at this, and we certainly don’t have a conclusive answer yet. This article suggests some ways in which culture may matter, but we can’t really know without asking the people who choose not to use bikeshare. For that reason, the title could probably also have been “the people no one is asking.”