Sports franchises hold a sizeable power dynamic over the municipalities that host them. This disparity allows franchises and leagues to continually extract large tax breaks and public financing for sports stadiums despite the lack of promised economic benefits. Asymmetric negotiation literature provides explanations to the current negotiation dynamics and strategies for cities to rebalance the power to reach more equitable outcomes.

In the national media, there is a discussion about the economic impact of sports teams, stadiums, and events and whether the claimed economic benefits justify the costs incurred by taxpayers to build the stadiums. Some cite the upfront and continual costs cities take on to bring in and keep franchises, the net losses for cities in tax revenue, and the ethics of using taxpayer funds to subsidize billion-dollar franchises as evidence against taxpayer funding for stadiums. A near-consensus of academic sources shows economic impacts are not worth the price tag, even when including spillover, externality, and non-economic benefits or political economy considerations.

Nevertheless, metropolitan areas suffer from an asymmetric negotiating relationship with sports franchises and leagues that disadvantages cities’ abilities to reach agreements with franchises that are equitably beneficial to both parties. Two cases from Ohio demonstrate how franchises exploit municipalities in negotiations and ways cities can rebalance power through tactics rooted in asymmetric negotiation literature, allowing residents to enjoy sports without being gouged by franchises and leagues.

Power Asymmetry

Asymmetric negotiating describes a negotiation process in which parties do not hold equal power. In symmetric relationships, actions by Party A benefit both Party A and Party B (mutually beneficial), whereas in asymmetric relationships Party A benefits at the expense of Party B (zero-sum). Stronger parties wield take-it-or-leave-it or take-it-or-suffer strategies while weaker parties struggle to re-balance power during negotiations. This leads researchers into two schools of thought concerning the transition between the symmetry of relationships and of outcomes: (1) stronger parties attempt to dominate negotiations to gain more favorable outcomes at the expense of weaker parties, or (2) weaker parties are not beholden to stronger parties in negotiations because the goals of the two parties are linked, suggesting weaker parties can rebalance power and reach a mutually beneficial deal.

Parties create asymmetric relationships mainly through displays of power. These displays typically come from three types of power: resources, networks, and relativity. Power from resources (possessional power) comes from the current and potential assets of a party and often manifests in coercive and structural exercises of power. Power from networks (power as relations) stems from sociopolitical connections. Stronger parties exert network power through personal, organizational, informational, or moral channels while weaker parties rely on actor, procedural, joint, and issue-specific tactics to rebalance power. Relative power (power as relativity) emphasizes that power is not absolute, is context-specific, and is fluid across the negotiation process, and negotiating powers rely on perceptions of an opposing power strength in decision-making; both in relation to themselves and in relation to the opposition’s past and future strength. Parties can also employ bad-faith tactics, namely deceit and exploiting trust, to create asymmetric relationships and induce asymmetric outcomes.

Asymmetric power does not doom a negotiation to asymmetric outcomes. However, when a stronger party exploits a weaker party into asymmetric outcomes, the outcomes tend to be less effective, efficient, stable, and satisfactory.

Asymmetric Negotiation in Sports

Currently, American sports stadium funding negotiations suffer from an asymmetric relationship between franchises and municipalities. The low supply of sports franchises relative to the high demand grants franchises and leagues asymmetric structural negotiating strength over municipalities. Further, anti-trust exceptions allow teams to further maximize their resource and network power through monopoly control. The relative asymmetry generated from this consolidation of power allows franchises to execute a negotiation playbook.

This playbook maintains and expands the power of stadiums vis-a-vis municipalities while preventing cities from balancing the power difference. The initial step: complain about the current facilities and threaten relocation (take-it-or-suffer) in the name of fairness and competitiveness (moral). Next, obscure the evidence (deceit & asymmetric information) through consultants who laud the economic benefits of building new stadiums, which can prevent changes in public sentiment and maintain positive perception and fame (celebrity) advantages. Then, set a restrictive deadline that prevents apt time for preparation and reduces the effectiveness of balancing tactics (namely procedural and joint exercises) to induce cities into making the initial offer and concessions on the way to an agreement. As the project is underway, exploit the city’s trust by increasing the demands, which the city is unlikely to refuse and risk an unfinished stadium project. Finally, maximize future bargaining power by including state-of-the-art clauses (procedural and issue-specific), to preempt the need to threaten relocation and avoid the resulting reputation costs.

Case 1: The Move

In the Cleveland Browns’ 50th season, owner Art Modell moved the franchise to Baltimore, violating the 25-year lease and his prior promises to never relocate. Modell made public his beliefs that Cleveland did not have the resources or the will to maintain a state-of-the-art facility, claiming $21 million in losses in the two years prior. Already having requested a ballot initiative of $175 million publicly funded renovations of the stadium, his announcement prompted voters to support the initiative with 72% of the vote.

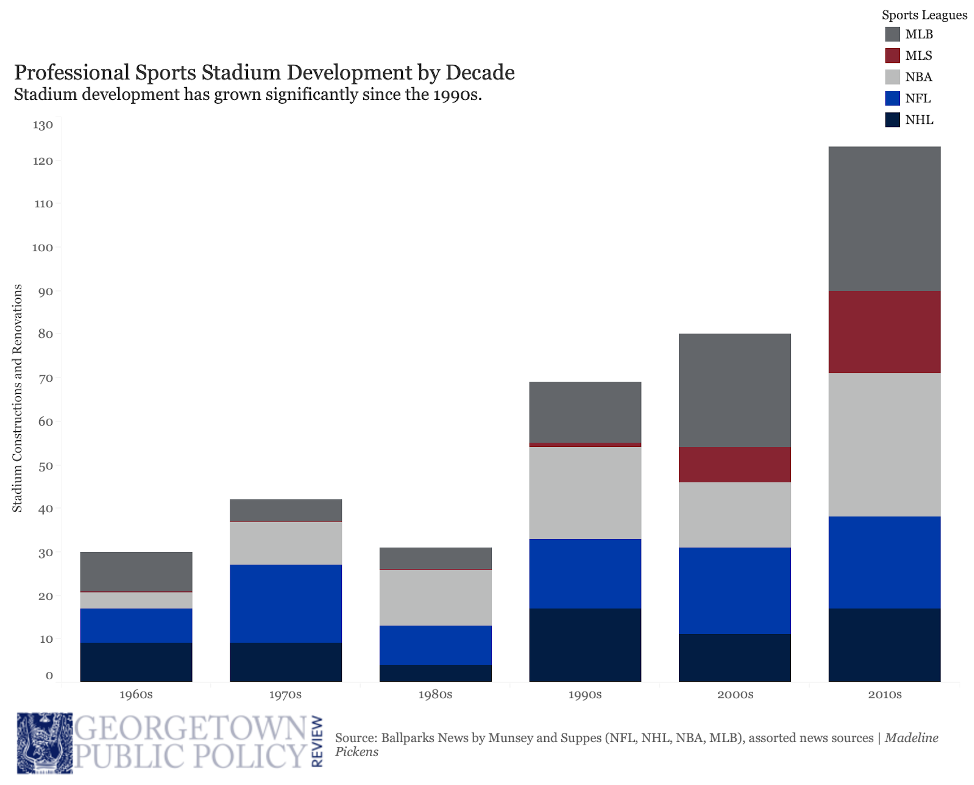

By this point, Modell has the best of every outcome; his immediate deadline prevented protracted legal battles and other equalizing tactics and the Browns could either return with the money and reputation or leave, strengthening the bargaining power of other franchises. This extreme version of the playbook prevented the City of Cleveland from reaching a settlement that might have kept the franchise in town or obtaining financial compensation for the loss; however, “The Move” (as it became known in Cleveland) also prompted post hoc examinations and an NFL-induced settlement that allowed Cleveland to retain the rights to the Browns and gain an expansion team in 1999. Modell’s move came in a climate of franchises threatening – and in some cases following through – on relocations, resulting in hundreds of new stadiums in the decades since.

Case 2: #SaveTheCrew

Largely in response to “The Move”, Ohio passed a provision preventing publicly supported teams from relocating without first providing six-months notice and an opportunity for the municipality to purchase the franchise. Columbus Crew owner Anthony Precourt, like Modell, claimed economic losses and unwillingness to fund a new facility as justification for his relocation efforts to Austin. However, media reports debunked many of the claims Precourt made, preventing him from controlling the narrative and provoking the growing public movement, #SaveTheCrew.

The city cited the provision in injunctions to stall the Crew’s accelerated deadline efforts. The ensuing public mobilization, including the 12,000 multi-game ticket pledges, public demonstrations, and encouragement of private sector involvement all worked to rebalance the asymmetry such that the MLS and Precourt agreed to sell the team to the Columbus Partnership. Further, a new stadium proposal with a 50-50 public-private investment passed. While the advantages that Columbus had (many of which came from the losses neighboring Cleveland had during “The Move”) cannot be fully replicated, similar protections and provisions at local and federal levels could help reach a more socially optimal outcome: symmetric negotiations leading to less public financing of stadiums without diminishing the quality or parity of the league play.

These case studies from Ohio expose a policy failure and how a state was able to implement and execute a change to rectify the failure. While not all of the elements are exportable from the Ohioan context, actions that assist municipalities in equalizing like time delays, objective program evaluation, encouraging public engagement, and capacities to call in third parties, empower cities in their negotiation to maximize their power sources and displays to reach symmetric outcomes.

| Symmetric outcome | Asymmetric outcome | |

| Symmetric relationship | Equal parties reaching mutually beneficial agreement | Party outmaneuvers and exploits opponent in agreement |

| Asymmetric relationship | Mutual interests align or weaker party rebalances to reach mutually beneficial outcome | Stronger party maximizes advantages and exploits weaker party |

Table 1: Diagram of conceptual link between symmetry of relationship and of outcome (The two case studies are examples of different outcomes from asymmetric relationships: The Move had an asymmetric outcome while #SavetheCrew reached a symmetric outcome).

Kalamazoo-born and Kansas City-raised, Daniel hopes to bring some of the Midwestern ethos eastward. Daniel graduated with degrees in French and Global & International Studies from the University of Kansas in 2019. As a Kenyan-American and an aspiring polyglot, loves and values diverse disciplinary and cultural/linguistic perspectives and how those interweave with policy needs and outcomes. In the rare moment away from Old North, Daniel is likely drawing, taking a long walk across town, or wonking out about politics, sports, or board games.