The English monolingual hegemony in American educational and economic institutions raises barriers for non-fluent English speakers, known as Limited English Proficiency (LEP) speakers. This article outlines the history of LEP advancement, the current condition for LEPs in the United States, and the pitfalls of the English monolingual hegemony for Americans regardless of English proficiency.

The institutional preference for English in the United States is at odds with our changing sociocultural dynamics. This disconnect disadvantages both Limited English Proficiency (LEP) and English-proficient (EP) monolingual Americans alike. In theory and in practice, American educational institutions embody those material disadvantages by failing to address the marginalization of LEP students and failing to adequately prepare EP students for our globalized communities and workplaces. While some reforms have been made, our faulty framework and disregard for the benefits of culturally supportive and multilingual education will continue to perpetuate these failings if left unaddressed.

In the 20th century, public policy practitioners and reformers made efforts to provide visibility and decrease barriers for LEP students in the United States. Meyer v. Nebraska was the first judicial opinion involving American education in foreign languages; striking down a Nebraska law preventing public and private schools from instructing in any non-English language as a violation of the Fourteenth Amendment Due Process Clause. Title VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Amendments of 1967 is one of the first recognitions of a state’s responsibility to accommodate the needs of LEP students. Over the next twenty years, amendments to the act, court cases including Keyes v. School District No. 1, Denver, Lau v. Nichols (the case which coined the term “limited English proficiency”), and Castañeda v. Pickard, and subnational action helped create guidelines for the implementation of those accommodations. These guidelines intended to help LEP students obtain instruction in their native language across all levels of education. These efforts also provided substantial funding, disbursing more than $162 million in 2000 and helped fund programs in more than 560 school districts.

Critique

Even with these improvements, a stigma and a set of negative perceptions remains for English Language Learners (ELL) in English as a Second Language (ESL) education. These biases – which stem from the effects of normalized English-only learning – lead to flaws in ESL testing, identification, and assessment, and decrease the quality of ESL-specific education. American institutions frame LEP status as a problem that needs to be resolved, rather than an opportunity to capitalize on the benefits of bilingualism and biculturalism (known as the deficit approach in the literature). Since the 1990s, academics have heavily critiqued the assumption that non-dominant language structures (including both languages and dialects) are deficient by exploring the internally-valid linguistic mechanics and the capacity for critical analysis within such structures. Later works also demonstrated that incorporating elements from non-dominant languages and dialects did not compromise or sacrifice the competency in the dominant language and instead had significant benefits. In fact, by (1) increasing the understanding of and (2) incorporating elements from non-dominant languages and dialects into education, institutions can deconstruct their biases, expectations, and preparedness – which in turn improves student outcomes. Transitioning from viewing proficiency in a non-dominant language or dialect as an inadequacy to an asset enriches the classroom experience for both students with high and low proficiencies in the dominant structure.

Issues Facing Limited English Proficient Residents in the United States

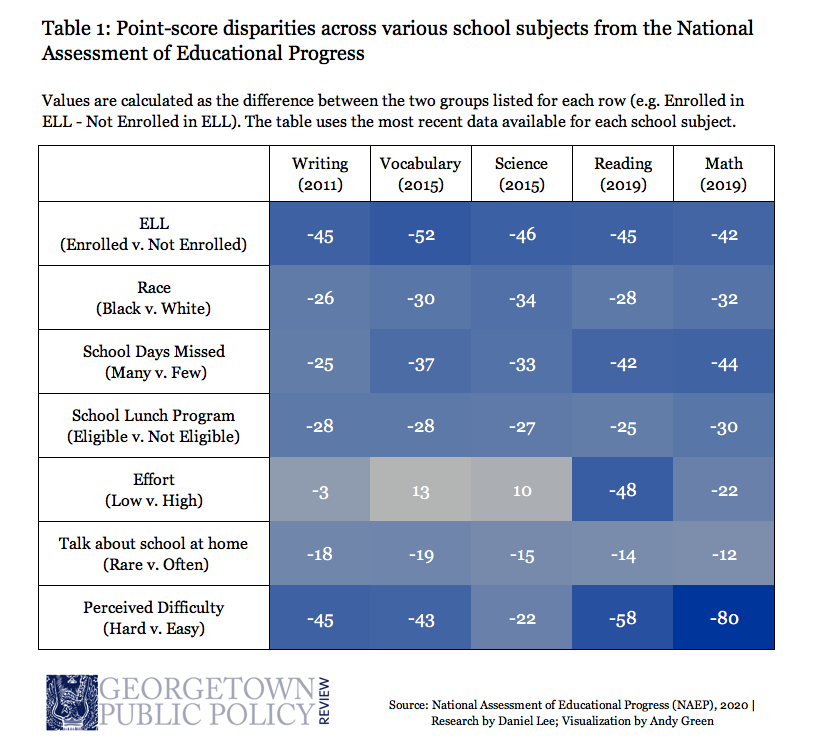

Educational institutions provide language acquisition accommodations for LEPs in the form of ESL programs. Despite the academic critiques, the current educational framework of most ESL programs still uses elements of the deficit approach by insufficiently incorporating culturally-supportive or multilingual educational practices and almost exclusively focusing on English acquisition. In spite of the fact that 90% of ELL students are enrolled in these language acquisition programs, these students continue to experience lower test scores and attainment as compared to their EP peers. The disparities between ELL students and non-ELL students are wider in terms of writing, vocabulary, and science scores than when comparing students by race, class (denoted by eligibility for the National School Lunch Program), attendance, effort, or perceived difficulty (see Table 2). The lack of adequate funding for ESL programs disincentivizes teachers from entering ESL and bilingual education tracks. Only 2.5% of teachers with ELL students in the classroom have ESL/bilingual education degrees and more than 30 states report ESL teacher shortages.

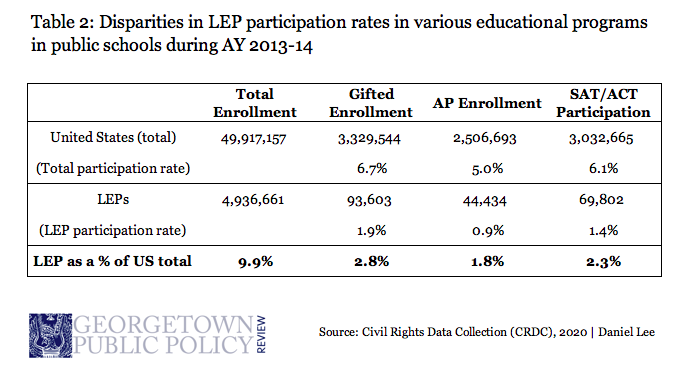

Test score disparities and a lack of funding further the systemic biases LEP students face in the classroom. Research shows teachers perceive ELL students as less intelligent. ELL students are three times less likely to be placed in gifted programs than their English Proficient (EP) peers, five times less likely to take advanced placement (AP) courses, and four times less likely to take college preparatory exams. This lack of support and constant bias help contribute to ELL students’ lower propensity to graduate high school – their graduation rates are 20 percentage points lower than the national average, with state data showing disparities as vast as 50 percentage points lower. In several states, the graduation rate for ELL students is less than 50%, the most egregious offender being Arizona’s 18% ELL graduation rate.

These disparities perpetuate and exacerbate cycles of poverty for LEPs in the United States. Almost half of LEP adults do not have a high school diploma, which is more than five times the rate of their EP counterparts. This constricts their workforce prospects: LEPs are more likely to work in service, construction, resource extraction, and personal care occupations. These jobs tend to pay lower wages – resulting in LEPs being twice as likely to live below the federal poverty line. Even when controlling other factors, LEP status adversely affects homeownership rates, healthcare access and outcomes, and access to justice – key elements to building wealth and avoiding financial hardship in the United States. This cycle hampers their children’s abilities to overcome the challenges their parents faced — particularly given the longstanding failures of federal policy to address the challenges facing students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Problems for English Proficient Residents in the United States

Beyond the burdens this hegemony places on LEPs, the limited focus on multi-language acquisition harms the prospects of EP Americans. At present, the US educational system fails to provide sufficient language acquisition and retention skills to prepare Americans for an increasingly multilingual country and workspace. Less than 1% of Americans retain proficiency in the language they studied in their domestic classrooms, despite more than 90% of high schools offering foreign language education. In the United States, there is a disconnect between the modern educational and economic opportunities related to multilingualism: foreign language instruction in elementary schools and foreign language enrollment in higher education are declining while one in five American jobs is tied to international trade, the demand for bilingual workers has doubled (for both high and low-skilled workers), and a majority of employers expect this demand to continue to grow. Further, links have been shown between foreign language study and improvements in cognitive development, memory, creativity, and problem-solving skills, which benefit students while in school and carry into the workforce. Also, studies indicate that students learning a foreign language experience a reduction in negative biases against speakers of that language. The shallow nature of America’s language educational approach demonstrates the policy disconnect between the English monolingual hegemony and the rapidly changing domestic and global circumstances.

Language acquisition could play a larger role in connecting our domestic communities through an increase in access for LEPs and a decrease in bias. However, our current preference for Eurocentric language acquisition fails to facilitate this end. The fastest-growing languages in the United States are South Asian languages (e.g. Telugu, Bengali, Hindi, Urdu, Punjabi, Gujarati) and a majority of non-Spanish-speaking LEPs speak a non-European language. While American schools have rightly placed emphasis on Spanish-language education – as Spanish is the second most spoken language in the United States – the preference for French, German, Italian, and Latin represent 21.5% of K-12 enrollment and 23.9% of university enrollment, despite speakers of these languages making up less than 2% of the Americans and 3% of speakers worldwide. Further, with more than 25 million LEPs in the United States, the disproportionate emphasis on French, German, and Italian – of which less than 5% of LEPs speak at home – does little in the way of supporting these communities. This critique is not to discredit the value in learning these languages – French remains a global lingua franca and Latin can provide solid foundations for medical, legal, and religious terminology – but the bias toward them misses out on the other opportunities multilingual language acquisition provides.

The National Center for Education Statistics found that American students not formally educated in American English by the age of twelve face significant disadvantages both as students and as adults. However, the same study also found that if LEP students went through formal education, not only would they have a significantly higher likelihood of English fluency but also of higher educational attainment and more financial stability. That study described students with formal education in American English through high school as being able to “master enough English to have earnings and employment patterns comparable to native English speakers.” This information, coupled with the scholarship critiquing the deficit approach and the advantages multilingualism provides, presents a need for policy practitioners to facilitate English acquisition without losing the advantages of bilingualism and biculturalism. While ESL programs have been found to substantially improve academic achievement, the vestiges of the deficit approach and the lack of adequate resources handicap these programs and isolate non-fluent English speakers from the rest of their cohort. Moving forward, more funding and programming for multilingual and ESL teacher instruction that emphasizes dual-proficiency education will help destigmatize ESL programs and ELL students, while also improving educational outcomes and language retention. A paradigm shift away from the English monolingual hegemony would increase access and attainment for LEP students while also allowing EP students to be more prepared for a 21st century America.

Photo by CGP Grey via Flickr.

Kalamazoo-born and Kansas City-raised, Daniel hopes to bring some of the Midwestern ethos eastward. Daniel graduated with degrees in French and Global & International Studies from the University of Kansas in 2019. As a Kenyan-American and an aspiring polyglot, loves and values diverse disciplinary and cultural/linguistic perspectives and how those interweave with policy needs and outcomes. In the rare moment away from Old North, Daniel is likely drawing, taking a long walk across town, or wonking out about politics, sports, or board games.