On January 3, 2020, the U.S. military ordered a drone strike at Baghdad International Airport that killed a high-profile Iranian commander, Maj.Gen. Qassem Soleimani, who led the Quds Force of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps. Gen. Soleimani was the mastermind of Iran’s military operations across the Middle East. The overnight drone strike also killed Abu Mahdi al-Muhandis, the leader of Kata’ib Hezbollah and deputy chief of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) an umbrella of militias in Iraq dominated by groups aligned with or sympathetic to Iran. The reason given by the Pentagon was that “General Soleimani was actively developing plans to attack American diplomats and service members in Iraq and throughout the region.” According to the Pentagon press secretary, the strike was also intended to deter Iran. Early on January 8, Iran attacked two bases that house American troops in Iraq by firing over a dozen missiles as a retaliation. Iranian Foreign Minister Javad Zarif later issued a statement on Twitter, stating that Iran does not “seek escalation or war” and that the missile attack was an act of self-defense.

News of the killing has led to a plethora of analyses and news coverage, mainly focused on the consequences and dangers of targeted killing, a possible war with Iran, and concerns from some senators and members of Congress who have called for consultation with Congress before taking deadly strikes. Some news coverage pointed out the president did not notify Congress before he authorized the taking of action. Specific calls included those from Indiana, with former Mayor Pete Buttigieg calling for “consultation with Congress” in regards to “matters of war and peace,” to Connecticut’s Chris Murphy asking whether Trump could “assassinate, without any congressional authorization,” to Democrat Rep. Jan Schakowsky calling on the president to “coordinate with Congress.” In speaking to NPR, Murphy further noted that Trump “does not have any other standing authorization to take out a strike against a country that we have not declared war against.” Some members of the UN Security Council – notably Russia – have condemned the attack. Iran has vowed to retaliate and it remains to be seen if the ballistic missile launches at bases in Iraq that host U.S. troops will be the only act.

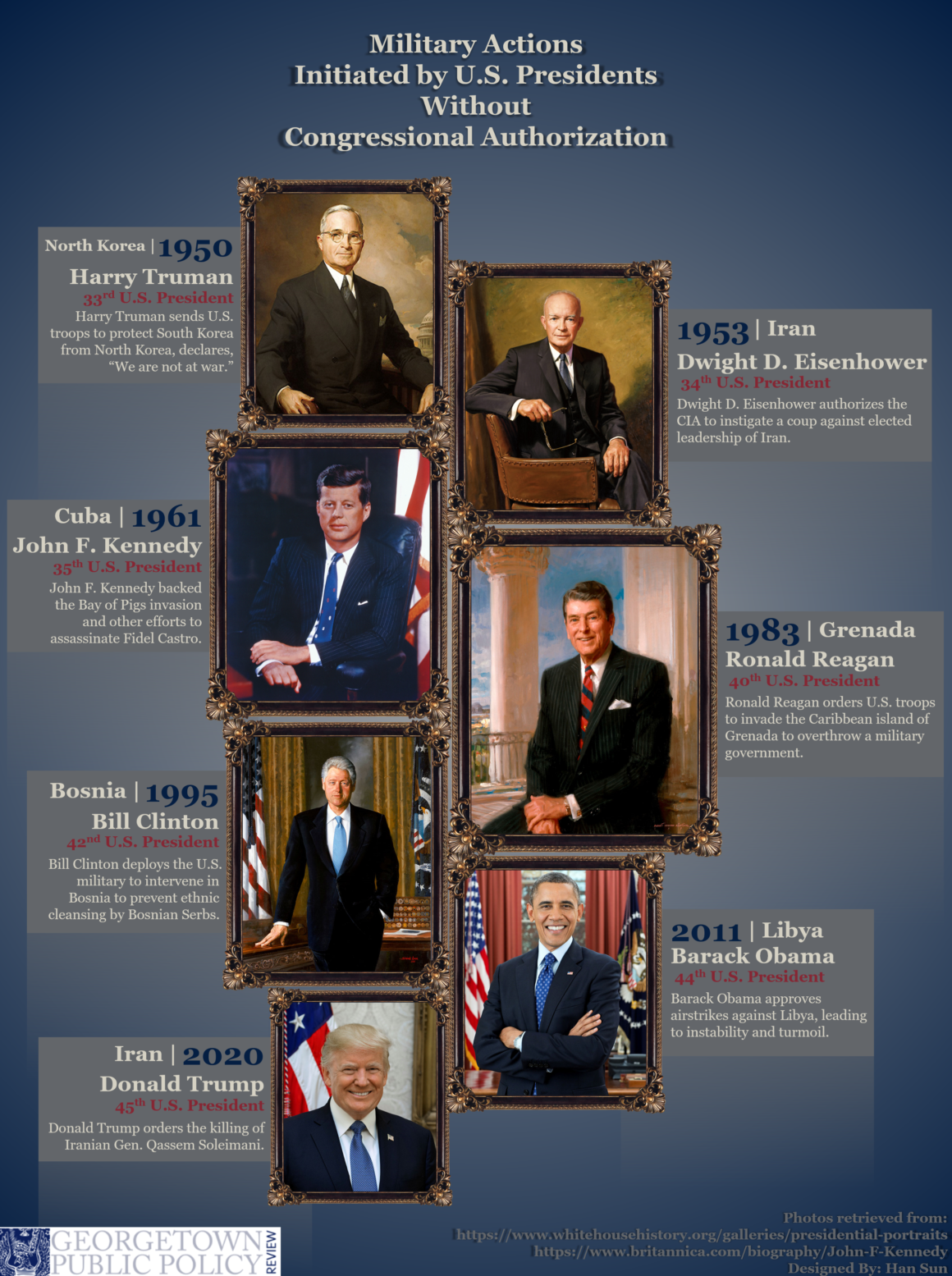

However, Trump’s decision to carry out a military strike overseas without Congressional approval or consultation is far from unprecedented. Since Truman, executive power has been vastly expanded mainly because of Congress’s acquiescence to presidential moves to take an expansive view of executive power. Moreover, a combination of U.S. federal court decisions have all undermined legislative attempts to rein in the executive. Presidents of both the Republican and Democratic parties – through a combination of executive initiative and congressional abdication – have engaged in large scale offensive wars, absent congressional war declarations. Much of the criticism in popular news media has little to do with historical precedence and more to do with political opposition to the presidency of Trump.

Did Trump violate U.S. law by authorizing the Soleimani drone strike?

Does the U.S. Constitution grant American presidents the right to carry out targeted killings? I argue the U.S. Constitution empowers the executive to carry out activities deemed necessary to protect vital interests of the United States. The potential sources of authority include AUMFs, the War Powers Resolution, and the Covert Action Statute. The potential limitations to this authority include congressional action and prior executive actions banning assassinations.

Currently, the United States relies on two Authorizations for the Use of Military Force (AUMFs) to conduct military operations in Iraq: 2001 AUMF and 2002 AUMF. The first provides the legal authorization to conduct military operations against al-Qaeda and related groups around the world. The second provides the legal authorization to conduct military operations to address “the continuing threat posed by Iraq” and authorized action in Iraq from 2003 to 2011 and against the Islamic State afterward. National Security Adviser Robert O’Brien asserted the 2002 AUMF likely provided the president with the statutory legal basis for the strike that killed Soleimani: the same AUMFs were used by President Obama to launch military action in Syria in 2014. Jack Goldsmith notes that since the attacks on September 11, the AUMF “remains the principal legal foundation under U.S. domestic law for the president to use force against and detain members of terrorist organizations.” However, one of the most remarkable legal development in American public law is the transformation of the AUMF from an authorization to use force against the perpetrators of the September 11 attacks and the conduct of the Global War on Terror and what Bradley and Goldsmith refer to as “indefinite war against an assortment of terrorist organizations in numerous countries.”

In addition to the legal requirements of the two AUMFs, there is the War Powers Resolution. The War Powers Act of 1973 requires that the U.S. administration submits a formal notification to Congress within 48 hours of military-style action. The White House provided Congress with formal notification of the Soleimani strike on Saturday of the same week after the strike was conducted. The War Powers Resolution does not place significant limitation on the executive power for actions that are short of 60-90 days. For any intervention beyond 90 days, the president must secure congressional authorization or withdraw U.S. forces from hostile theaters of operations.

Limitations on the authority to conduct these military action include direct congressional acts and prior executive orders. Assassination is prohibited by a number of U.S. executive orders, notably President Ford’s Executive Order 11905 and President Reagan’s Executive Order 12,333. While assassinations are illegal political acts, “targeted killings” are differentiated as military strikes, conducted strictly for security concerns. What Trump needs to provide to Congress and the American people is overwhelming evidence of an imminent threat that Soleimani posed to United States and its national interests.

Furthermore, Bradley and Goldsmith report that even when Congress does not authorize targeted killing under AUMF, the president could still carry out targeted killing against targets that present an imminent threat against U.S. interests under the Covert Action Statute (CAS), 50 U.S.C. §413b.

A history of military action without Congressional action

Since President Harry Truman in 1945, modern U.S. presidents have exercised powers far beyond those delegated to them in the Constitution. As noted by Louis Fisher, Eisenhower’s administration authorized covert operations in Iran and Guantanamo, President Kennedy’s ill-advised operation in the Bay of Pigs included plans for assassination of a foreign leader, Reagan exercised broad powers and got involved in Grenada and in the Iran-Contra affair, Bill Clinton was involved in Bosnia without congressional authorization, and Barack Obama conducted military action in Libya based on United Nations (UN) and not congressional authority. While President Bush initiated a targeted drone strike campaign in the global War on Terror, Obama sharply increased the global campaign with bipartisan support.

The trend among U.S. presidents has been to rely on executive power to commit U.S. forces overseas and at times rely on UN Security Council resolutions and approval from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) to legitimize intervention than seeking congressional approval. For most of his military interventions in Iraq, Somalia, Haiti, Bosnia, Afghanistan, Sudan and Kosovo, President Bill Clinton circumvented Congress and instead sought support from the UN Security Council and NATO allies. Following in the footsteps of Truman, President Bush claimed unilateral power in the Global War on Terror, authoring warrantless wiretaps inside and outside U.S. borders, and devising coercive interrogation techniques that later turned out to violate U.S. laws and erode civil liberties. Obama followed in the same footsteps when he sought permission from the UN and NATO and not Congress when the United States intervened in Libya to topple Muammar Gaddafi in 2011, as well as substantially expanding use of covert drone strikes in Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Libya, as well as covert operations in Pakistan, Yemen and Somalia, including against at least one U.S. citizen (Anwar al-Awlaki). Obama’s action involved no congressional authorization of the use of force.

There is nothing particularly unusual in how Trump has proceeded to interpret existing statutes to carry out a military strike overseas. If anything can be learned from history, it is many post-World War II U.S. presidents have liberally read congressional statutes to authorize interventions in foreign theaters of operations. We also know that there is nothing idiosyncratic about the action when compared with past U.S. presidents.

On matters of executive power to launch military operations outside the United States, legislators have often abrogated their constitutional responsibilities. The result has been a steady erosion and usurpation of legislative power, which has granted presidents vast constitutional authority as commanders in chief and chief executives and substantial discretion to use lethal force in the national interest. The executive usurpation of legislative power did not start with Trump, and, indeed, it has traditionally enjoyed a longstanding bipartisan consensus in Washington. The main times it (sometimes) is criticized from one half of Congress is when the president in question is from the opposing political party.

Banner photo courtesy of U.S. Air Force photo/Ilka Cole