The spread of misinformation in the news is increasingly problematic, as the rise of partisan news media undermines existing incentives for journalists to issue corrections. Instead of reacting with government regulation of speech, a court process could allow competing media platforms the right to correct each other. Under this proposed “hostile corrections” law, when a news media outlet publishes misinformation without appropriate and timely self-correction, an opposing outlet with sufficient proof could issue a correction on the misinforming media platform’s airtime, website, or pages.

What keeps journalists accountable?

Because the American ideal of free speech has overshadowed interests of journalistic accountability, U.S. law does not penalize the spread of political misinformation. Instead, the only process that seeks to counter misinformation in the news is self-correction.

Media scholars 20 years ago argued that voluntary self-corrections are crucial to the “reputation for accuracy” on which the news media builds its viewership. These policies for dealing with corrections were self-imposed by leading newspapers and then followed by others as written corrections policies, mission statements, and an aspirational code of ethics. Today, consultants to journalists note that maintaining credibility is the key reason for issuing corrections, and consultants to others note that corrections are something you must request, not demand, of journalists.

However, something is fishy with the idea that more corrections continue to inspire more trust. In recent incidents, an admission of regular correction amounts by a journalist and an innocuous slip-up by a newspaper each garnered responses that used the mistakes to argue that the mainstream media is “fake news.” In each case, the reporting journalist called for more corrections as the best response. However, researchers point out that there is no empirical evidence that the general public appreciates corrections as much as journalists do, and there is empirical evidence that misinformation persists after a standard correction.

Using mere reputations for accuracy as motivation for corrections becomes more problematic under the adoption of new business models in the news media.

A dwindling concern for correcting misinformation?

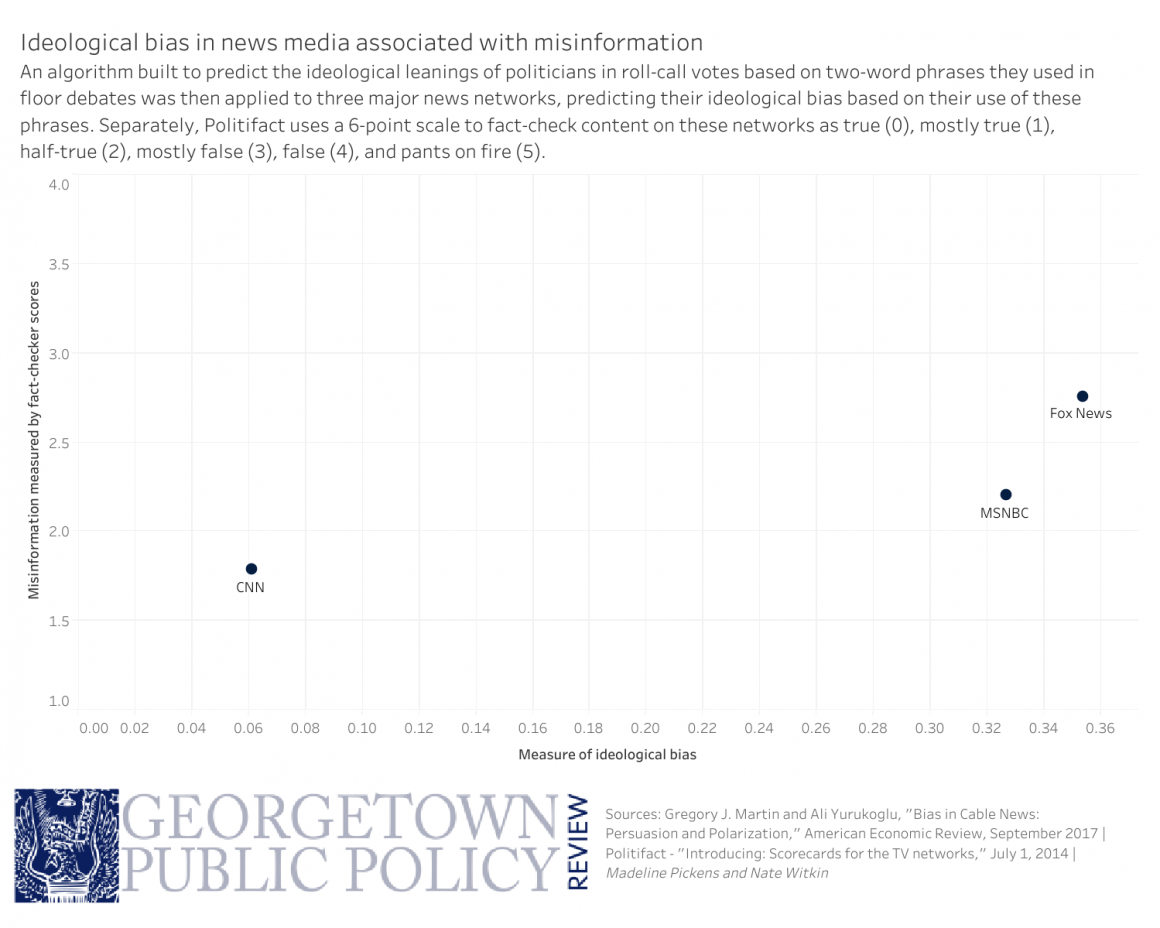

Repeated studies have supported the existence of a “hostile media effect,” in which both sides of the political divide perceive a hostile bias from the same news content. With the recent expansion of media sources, growing consumer choice leads viewers to gravitate toward media outlets that express a favorable partisan bias, and fierce competition for ratings pushes news outlets to adopt a partisan slant. This emergence of a Fox News/MSNBC business model and subsequent polarization of news media content indicate an accelerating tendency of news outlets to tell viewers what they want to hear.

These tendencies present implications for the distinction between media credibility and media trustworthiness. Credibility appears to be affected by perceived accuracy of the media, whereas trust appears to be affected by perceived bias in choice of topics and commentary. This distinction is important because studies have found that partisan viewers tend to infer the credibility of news based on whether they trust the source, and people who do not trust a source are not mollified by corrections. Therefore, reliable bias may become more important in conveying credibility than actual accuracy.

As partisan news sources pander to increasingly distinct audiences, the concern for credibility that has motivated the correction of misinformation in the news may be replaced by consistently partisan messaging by news outlets.

The solution: Hostile corrections

Our increasingly polarized news media environment calls for a new, potentially effective mechanism to fight political misinformation—the hostile correction. Under this process, when one media company reports information that turns out to be false and does not issue a sufficient and timely correction, an opposing voice would be able to file a lawsuit to present the correction on the misinforming company’s platform.

To illustrate the process, if Sean Hannity were to cite a source in making an argument, and that source turned out to be a hoax, but Hannity did not make a correction after a predetermined period of time, then other media could file a court action. If MSNBC made a formal request for a correction and convinced a judge that Hannity spread misinformation that was not corrected after the request, the judge could order Fox News to air MSNBC’s presentation of the “hostile” correction.

Alternatively, if the Washington Post used a story (e.g., Covington Catholic) to support an anti-Trump argument and did not post a retraction at the bottom of the online article after the story was refuted, the Wall Street Journal could take legal action to possibly edit or append to the original article.

This would motivate the effective correction of misinformation because partisan news networks would not want to give the opposing ideology the ability to frame the correction. Furthermore, social scientists studying misinformation and political misperceptions argue that corrections are more effective when they are delivered by a source with the same ideology as the source being corrected.

Parameters of a hostile corrections law

In order to create effective disincentives against misinformation without unfairly burdening media outlets, hostile corrections laws should follow a few basic parameters.

First, these policies should be limited to political reporting. Not only is politics the fulcrum around which news media are becoming polarized, but while private citizens have recourse to defamation laws to correct published misinformation, political reporting is not often regulated by these laws because of First Amendment concerns. Furthermore, because many errors published by news platforms are unintentional misspellings and typos, limiting hostile corrections to political reporting would avoid a situation in which an overwhelming flood of litigation from private citizens distracts media outlets from their journalistic functions.

Litigation burdens could be further minimized by limiting petitioners of hostile corrections to the media outlets themselves. As partisan media outlets have seen disproportionately more revenue in the last decade, while also running afoul of fact-checkers, allowing them to litigate misinformation could pose both a check on their profit motive and a valid use of their growing resources.

Second, hostile corrections law should require that corrections be made with “due prominence.” Due prominence is a guiding concept for journalists that recommends that corrections be made as prominent as the presentation of the error corrected. Therefore, when the original source issues a correction to head off a hostile correction process before it begins or when an alternative perspective wins the ability to issue a hostile correction at the end of the process, the correction must be given equal prominence in coverage as the misinformation.

Finally, as a guiding best practice, the form of corrections and hostile corrections should take the form of a cogent narrative and not a bland statement retracting the misinformation. Because studies indicate that simple retractions are not effective at countering misinformation, especially for a partisan audience, social scientists recommend that corrections be delivered in a compelling narrative structure, similarly to how typical news stories are delivered.

Implications of hostile corrections

In the face of an increasingly partisan media, hostile corrections may deter misinformation and political polarization among news outlets. And while hostile corrections should begin with cable news, news websites, talk radio, and newspapers, this policy may have implications for other platforms.

If applied to social media, users who disprove fake news posts could compel the platform to target their correction to affected users whose siloed social networks can create echo chambers of misinformation. And, if applied to politics, hostile corrections could take the form of a “Corrections Committee” that could compel politicians to testify about blatantly false claims.

In an environment that threatens to tip into a post-truth world, people who believe that the media spreads misinformation may support an individual right to correct it

Header photo by Mark Bossingham.

Nathan Witkin is a second-year MPP student who practiced law and served as a mediator for 10 years before enrolling at McCourt to study public policy innovation. His ideas published outside GPPR include the interspersed nation-state system, interest group mediation, dependent advocacy, a police-community partnership model for citizen review boards, a novel framework for sovereignty in a globalizing world, co-resolution, consensus arbitration, executive bargaining, a theory of impact bonds, and an alternative explanation of gravity.