Anti-immigrant rhetoric from the White House fails to recognize the country’s legal obligation to asylum seekers and instead seeks to criminalize migrants. The ad hoc arrangement of immigration policy in the United States is wrought with inconsistencies and ill-equipped to deal with the modern realities of human displacement, presenting a serious threat to the country’s longstanding humanitarian tradition.

U.S. immigration policy over the years

Global human migration is constantly changing in scope, kind and scale and yet, current U.S. immigration law continues to ground itself in a definition of “refugee” that is no longer adequate. In the wake of World War II, the 1951 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees set out to define the modern concept of a “refugee” and establish the international community’s responsibility to protect the world’s displaced and persecuted persons. Since the 1951 Convention, the U.S. immigration system has been pieced together through decades of policymaking, which tend to reflect the country’s geopolitical interests at any given point in time. Today, the United States is one of 142 states to ratify both the 1951 Convention and the subsequent 1967 Protocol, signaling the nation’s dedication to protecting the world’s persecuted and displaced populations. At the time, U.S. policymakers were greatly influenced by Cold War politics, as the hundreds of thousands of migrants fleeing communism and granted entrance into the United States could be used to demonstrate the allure and triumph of democracy.

The relatively lenient parole policy adopted during the Cold War began to shift in the 1980s when the United States faced a dramatic increase in asylum applications, mainly due to political turmoil across Central America. In response, Congress adopted the 1980 Refugee Act, which codified the UN’s definition of “refugee” into U.S. law, with the hope of securing a permanent track for refugee admission into the United States. Given this definition, those who cannot return to their country of origin due to a “well-founded fear” of past or future persecution “on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion” qualify for refugee status.

By the 1990s, America’s sympathy towards refugees dissipated further, as geopolitical concerns about the economy and national security have come to dominate immigration policy. Following the 1993 and 2001 World Trade Center attacks, politicians sought to mollify public fears by further tightening the necessary criteria for granting asylum in order to secure our borders. Politicians began using the term “economic migrant” to arouse public fears that the American job market could be flooded by migrants voluntarily leaving their homes in search of betterment. Over decades of policymaking, the immigration system has evolved to encompass numerous government agencies in an attempt to balance state sovereignty and human rights – that is, the securitization of borders and the protection of refugees.

Asylum adjudication: Inconsistent and unfit for modern migration

U.S. immigration law has failed to evolve alongside changing forms of migration, shifting to an increasingly hardline set of policies that are more intent on deporting and criminalizing migrants, than providing them with a safe place of refuge. The patchwork of immigration policies put into law since the mid-twentieth century have resulted in a complex asylum process that is not only inconsistent, but often inhumane. Immigrants arriving at our border must navigate this complex system as they apply for asylum – a protection granted to foreign nationals on a case-by-case basis, given that they can prove a “well-founded fear of persecution,” and thus qualify for refugee status. While this seems straightforward, vast inconsistencies in the asylum adjudication process exist due to the fact that there is no explicit U.S. statute to determine what qualifies as a “well-founded fear of persecution.” As a result, asylum officers and immigration judges are given vast discretionary power to determine the status of each case, leaving the standard of proof vulnerable to change on happenstance.

Inconsistencies that may arise as a result of discrepancies in individual asylum officers’ and immigration judges’ interpretation of the law defining “refugee,” are magnified by the fact that there is no free or mandatory access to legal counsel for asylum applicants. Moreover, the burden of proof in each asylum case is entirely upon the individual applicant, who must overcome language and cultural barriers to prove their case to the immigration judge or officer. Thus, not surprisingly, it was found that asylum applicants represented in court were granted asylum at a rate almost three times that of applicants without legal representation.

Moreover, the increasingly complex dynamics of modern migration pose a vital challenge to policymakers in Washington. For example, climate change and globalization are two forces creating movements of irregular migrants, who fall outside of the current refugee protection framework, but nevertheless need protection. The concept of “mixed-migration” has also been recently introduced into the policy arena to describe migratory movements in which migrants and refugees – or, voluntary and involuntary migrants – travel together. Likewise, individuals’ motives for migrating may be mixed as well; as in many cases, conflict and poverty co-exist or even feed one another. As a result, the distinction between refugees and migrants becomes increasingly blurred, leaving asylum officers and immigration judges in the position to make potentially life and death decisions.

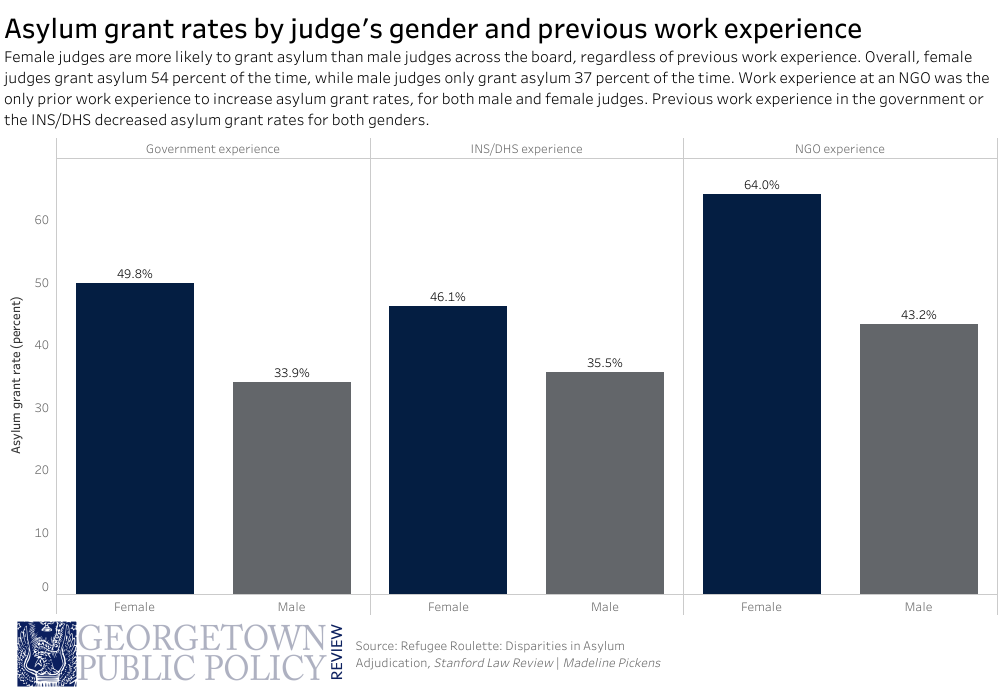

As policy fails to adapt to modern forms of migration, it is not surprising that the asylum adjudication process is wrought with inconsistencies, often at the expense of human rights. In fact, a groundbreaking study published by the Stanford Law Review analyzed 140,000 decisions by 225 immigration judges, concluding that asylum adjudication is nothing but a game of chance. Coining the term “refugee roulette” to describe the asylum process in the United States, the authors of the study revealed considerable disparities among asylum grant rates dependent upon various factors such as a court’s location, the judge’s sex and professional background, and the quality of the applicant’s legal counsel. For instance, the study found that Colombians had an 88 percent chance of being granted asylum from one judge, and only a five percent chance of winning asylum from another judge working in the same federal Miami immigration court.

Potential policy reform: Balancing national security and international obligations

U.S. immigration policy has proven ill-equipped to deal with the modern realities of human displacement. To make matters worse, instead of taking steps toward developing a comprehensive policy to manage new forms of migration, President Trump has made it his mission to criminalize migrants for his own political gain. Despite record low numbers of illegal border crossings that have sharply decreased in the decade from 2006 to 2016, Trump managed to use the issue to rally support along the campaign trail. In April, the administration adopted a “zero-tolerance policy,” seeking criminal prosecution of all who crossed the border illegally, which infamously led to the separation of more than 2,500 children from their families. Trump has not only targeted illegal border crossings, but he has also limited migration into the United States on a whole, reducing the refugee admission cap to 45,000 for FY 2018, the lowest since the enactment of the Refugee Act in 1980.

The authoritarian methods adopted by the Trump administration threaten the country’s international obligations and humanitarian tradition. To uphold the country’s international responsibilities and maintain the credibility of our asylum system, extensive reforms will be necessary to streamline admissions and transform asylum adjudication from a game of chance into a viable route for persecuted persons to receive protection. To minimize protection gaps and manage mixed-migratory populations in a way that respects individual’s human rights, policymakers should construct explicit statutes outlining criteria for refugee status determination that acknowledge that migrants do not always fit into the established categories of persecution.

Photo by Daniel Arauz via Flickr.

1 comment

A very well written article.

I’m not a public policy expert but I understand the importance it has to our daily lives and, more importantly, our future lives. Instead, as an engineer, I view issues such as migration and drug trafficking (both border sensitive issues) in terms of economics and, probably somewhat strangely for most, the laws of physics. In many ways they provide similar insights

Borders are a somewhat arbitrary construct. It reminds me of a joke I heard in high school. The border between Poland and Russia needed to be redrawn. A farmer’s house would have been dissected by the new border. When he was asked which side he wanted to live on, he relied “The Polish side. I can’t stand the Russian winters”. And yes I know Poland doesn’t border with Russia. But it just sounds better when told that way.

In the US there are two primary land borders: Mexico and Canada. No one is suggesting building a wall on the northern border even though the biggest offenders with respect to visa overstays are Canadians. And to be clear on this, it doesn’t matter if you are undocumented in the US because your crossed from Mexico to the US via the southern border or your overstay your visa. It’s the same. But for the most part, Canadians look like many people in the US. They sound much the same and they have comparable education and income levels. Basically they are almost one of us.

So this is where economics and physics comes in. I conceptualize economic pressure differences on the northern border as almost zero. But in economics, like in nature, pressure differences across a membrane (a border) will try to equalize that pressure (osmosis). So on the southern border there is a huge economic disparity between the US and Mexico/Central America. Sadly, this economic disparity has been exploited by corporations moving operations to lower income regions. This meets their principal goal of increasing profit but it does little to equalize this economic imbalance. In fact it perpetuates it.

Many people know of Henry Ford’s decision to raise the wages of his factory workers to $5 a day. Now the actual reason may not have been to enable them to buy the product he was selling i.e. increase his market. But that is what happened. And it benefited the local and national economy as others followed suit. And the economic pressures that existed between those competing for the workforce equalized as others started to pay their workers more. But that is precisely what has not happened south of the US. Instead, every increasing sums of money have been used to control US borders. And, much like the “war on drugs”, it is likely that ever increasing amount of money is required to combat every increasing economic pressures but with little tangible benefit and significant hindrance to economic and human development both sides of the southern border.

How many more customers in Mexico/Central America would be available to the US if, instead of creating fortress US, some of that money was used to help develop those markets to everyone’s benefit. Think of the Marshall Plan to help rebuild after the Second World War. What a stroke of genius that the only country with a largely intact means of production, the US, helped to create the economic activity that made this country what is it today, economically speaking. The US share of world GDP peaked about 1950 and 40% and has had been declining ever since for good reason: Other countries started to produce more. But the US GDP continued to rise in dollar terms (allowing for the various recessions along the way) from 1945 onward.

The goal should be a border that does not require a massive cost to maintain. Like the US/Canada border. But although we need to address the human damage that is all to plain to see, we need to invest in solutions to reduce the economic imbalances that exists for no other reason other than short term gain. Germany and Japan were in a worse economic condition that many of the countries to the south of the US. Today they are some of the most economically powerful countries on the planet and valuable trading partners to the US. That didn’t happen by accident.

Comments are closed.