South Asia has been marred by constant intrastate conflict. Over the past few decades, sustained insurgency movements have proven detrimental to the health of the region and its people. This article is the first in series on the rise, fall, and triumph of South Asian insurgencies in three states in the region: Nepal, Sri Lanka and India.

Part I : How insurgencies succeed – Nepal

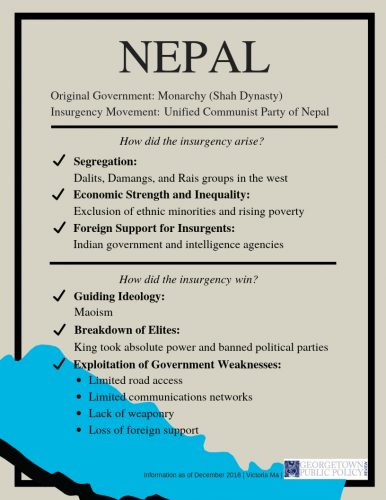

Unlike many insurgencies, Nepal’s proved triumphant in achieving its goals. In May 2008, Nepal’s newly formed interim government abolished the country’s 240-year monarchy. This event can be traced back to the Maoist insurgency that began in 1996, whose stated aim was to declare the country a republic. In just over a decade, these insurgents achieved their goal.

What is an insurgency?

The most comprehensive definition of insurgencies comes from the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), which defines an insurgency as “a protracted political-military struggle directed toward subverting or displacing the legitimacy of a constituted government or occupying power and completely or partially controlling the resources of a territory through the use of irregular military forces and illegal political organizations.”

Insurgencies can be viewed from two different perspectives: as a tactic and as a strategy. According to Rich and Duyvesteyn, when viewed as a tactic, insurgencies are often used interchangeably with guerilla warfare, where the main goal is to exploit the opponent’s conventional military weaknesses. However, when viewed as a strategy, an insurgency can be defined as “an organized movement aimed at the overthrow of a constituted government,”

Regardless of context, insurgencies have several qualities in common. According to the CIA, insurgencies are fundamentally a “political struggle” and are “unlikely” to be defeated by military means alone. Insurgencies also commence their struggle in a weaker military position than the government and therefore seek to avoid lengthy direct military confrontations with the government. They depend on the local population for support, though not all support comes from “true sympathizers,” for which insurgents often intimidate the population into supporting them. Insurgents try to coerce people to pick a side and aim to provoke government forces to commit abuses that might alienate the neutral population and drive them toward the insurgents or solidify their loyalty for the insurgency. Additionally, to succeed, insurgents may only obliterate the government’s political will and not necessarily defeat it militarily.

Nepal: The Maoist insurgency

Nepal was united by King Prithvi Narayan Shah in 1768 after he successfully annexed several feudal principalities spread across the South Indian region. Ever since its establishment, the monarchy became the primary institution of the country, with power shifting between two elite families: the Shahs and the Ranas. While democracy seemed imminent after the pro-democracy revolutions against the Rana regime during the 1950s, upon power shifting from the Rana to the Shah Dynasty, the 1960s then brought in a party-less political system that gave absolute power to the Shah Kings. It took approximately 30 years for another revolution to take place that reintroduced democracy and removed the party-less absolutist system in 1990.

Nepal was united by King Prithvi Narayan Shah in 1768 after he successfully annexed several feudal principalities spread across the South Indian region. Ever since its establishment, the monarchy became the primary institution of the country, with power shifting between two elite families: the Shahs and the Ranas. While democracy seemed imminent after the pro-democracy revolutions against the Rana regime during the 1950s, upon power shifting from the Rana to the Shah Dynasty, the 1960s then brought in a party-less political system that gave absolute power to the Shah Kings. It took approximately 30 years for another revolution to take place that reintroduced democracy and removed the party-less absolutist system in 1990.

It was against this backdrop that the Maoist insurgency emerged in 1996, after multiple disparate Maoist groups became dissatisfied with the results of the 1990s people’s movement that reintroduced multi-party democracy. Younger leaders challenged older leaders from multiple communist parties and eventually helped regroup themselves as the Unified Communist Party of Nepal (Maoist) (UCPN-M).

The origins of this Maoist insurgency can be traced back to the royal family’s use of the state for personal gain, backed by the upper-class elites. While the majority of the population lived in dire poverty, the royalty and its cronies lived luxuriously. The rich-poor divide is especially stark in Nepal’s western region, which was also a stronghold of Maoism and the launchpad of the insurgency. With limited cultivable land and road access, the dissatisfaction of the minorities in the west further increased as the feudal class within and beyond the region prospered. Nevertheless, the inequality did not just exist between the west and the rest of the country. Even outside the west, there were many who never experienced economic security, especially in the context of minority groups. As noted by Prabin Manandhar, the poor and the disadvantaged in other parts of the country were aware of the inequality, and the Maoists cited this exploitation to advocate for insurgency.

India too played a defining role in the launching of Nepal’s insurgency. While Maoists did criticize India’s intervention in Nepal at the beginning of the insurgency, the criticism was only verbal. There was suspicion that India’s ties with Maoists caused them to remain silent after Indian troop placement at the India-Nepal border in 1996 led to a 1998 border dispute. While this dispute was heightened by the political elites in Kathmandu, the Maoists were explicitly absent from the conversation. According to Puskar Gautam, a former Maoist who abandoned the insurgency, “India might have expected more from the Nepali democrats on the basis that Nepal’s democratic and communist movements were made possible only thanks to India’s support. However, its expectations may not have been met in the new political scenario that emerged after 1990, hence it may have decided to use the Maoists as a bargaining tool.” Additionally, while there were multiple reports of Nepalese Maoist leaders meeting Maoists in India, they were overlooked by Indian intelligence agencies, despite many of the Nepalis being on Nepal’s terrorism list.

The triumph of the weaker force

There are numerous reasons why Maoist insurgents were able to accomplish their goals. First, the Maoists utilized the weaknesses of the Royal Nepalese Government. For instance, the Maoists functioned in remote villages beyond the reach of the government, which helped them to elevate the conflict’s intensity for their benefit. As noted by Avidit Acharya, there was a direct link between road density, which is the distance of a road measured in kilometers as a percent of 100 square kilometers of surface area, and the number of conflicts. This showcased a decline of up to one death per 1,000 people associated with a 10 percent upsurge in road density. Additionally, government communications networks were weaker in rural areas. As the conflict continued, the anger arising from socio-economic difficulties fueled the Maoist insurgency. The underdeveloped midwestern region, for instance, was also associated with substantial uptick of approximately one death per 1,000 in a research sample that included underdeveloped regions such as Rolpa and Rukum.

While the Royal Nepalese Government was supported by foreign nations, specifically India, this support was only superficial. In contrast, the Maoists had developed a healthier relationship with Nepal’s southern neighbor. Journalist Rabindra Mishra provides an example when then-Prime Minister Sher Bahadur Deuba’s visit to India was intercepted by three senior Maoist members attempting to meet him, reportedly being escorted by Indian intelligence.

The issue was further exacerbated after the Royal Massacre of 2001 that killed the popular King Birendra and his family, bringing his younger brother, King Gyanendra, to power. A few years after King Gyanendra ascended the throne, he instituted an absolute rule in 2005, banning all political parties. This action turned a tripolar conflict between the king, the political elites, and the Maoists into a bipolar conflict between the king and the other two groups. Thus, the decision of the king to take absolute power led to the defection of the political elites while angering the rest of the population.

Lastly, the Royal Nepalese Government towards the end of the conflict also possessed limited resources to fight the insurgents. According to the Times of India, a diplomatic cable released by Wikileaks stated that the government’s “arsenal had started dwindling alarmingly” after not only India but also the United States and the United Kingdom stopped their supply of arms the previous year to signal their disapproval of the 2005 royal coup.

While Nepal provides an example of a triumphant insurgency, other South Asian movements were less successful. The Nepalese Maoists, while fortunate to have multiple conditions favorable to their triumph, were also successfully able to capitalize on the weaknesses of the Royal Government of Nepal. The government, in contrast, had a string of difficulties, including limited foreign support, along with the misfortunes that befell the Royal Government with the murder of King Birendra and his family. This was made worse upon the disastrous political miscalculation by his successor, King Gyanendra, to take absolute control of the country.

The next part of this series will focus on the defeat of Sri Lanka’s insurgents, followed by an analysis of India’s ongoing insurgency.

***

Photo of government police and Maoist rebel police at the Nepal border by Bo Jayatilaka via Flickr.

Ayush Manandhar is from Kathmandu, Nepal. His experiences include working with both government and international institutions, including the Embassy of Nepal in the United States, the United Nations Human Settlements Program, and Winrock International, among others. Recently, he served as the Fellow for Intercultural Engagement at his alma mater, Westminster College, where he led events and improved policies for the college’s minority students. As a student, he was the editor-in-chief of Westminster Journal for Global Progress, the flagship journal of the college. Having traveled widely and having seen people face widespread poverty and disparity, Ayush is motivated to uplift the lives of the many underprivileged people around the world. He hopes to write more on policy and politics as a part of this journey.

1 thought on “The rise, fall, and triumph of South Asian insurgencies: Part I – Nepal”

Comments are closed.