Public policy is complicated. To make it less complicated we’ve decided to break it down by creating an initiative dedicated to the rigorous study of more singular policy topics released in series. Over the coming months readers can expect a thematic stream of content from these series, that tell a story about a relevant but tricky policy. Our first series is the namesake of this article. This of course begs the question – why spend time discussing prescription drug pricing?

In September of 2015, the New York Times reported that Turing Pharmaceuticals had increased the price of Daraprim, a HIV/cancer treatment drug, by over 5000% after acquiring the rights the drug in August. In the weeks and months that followed, the story would dominate headlines, a phenomenon kindled by the unlikeable and raucous public personality of then CEO Martin Shkreli. Arguably the architect of his own destruction, this past February Shkreli had the unenviable position of being hauled before an angry House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform. Republicans and Democrats both lambasted Shkreli, the FDA, and anyone else who happened to be on the witness list that morning and for a brief moment, it seemed as though the issue of drug pricing was about to have its day.

Shkreli would eventually step down as CEO, and with his departure public attention was drawn away from the issue of drug pricing and towards the excitement of a particularly controversial presidential election. The issue would stagnate in the news cycle over the next several months, but by June a new character in this saga had emerged. Mylan Pharmaceutical’s EpiPen, an epinephrine auto-injector used to combat allergic anaphylaxis, was found to have increased in price by more than 500 percent over the last decade. For better or worse, the device, used by millions nationwide, now commanded headlines as the most recent poster child for corporate greed.

By now a pattern had begun to emerge, and Congress wasn’t about to let itself appear to be fooled twice. In a scene that had now become all too familiar, Mylan CEO Heather Bresch was brought before the House Oversight Committee and aggressively questioned for a grueling four-hours. With headlines again dominated by the EpiPen, the issue of the price of prescription drugs was beginning to turn into a household policy discussion. Both presidential candidates quickly adapted by issuing policy positions promising to solve the problem of high-cost prescription drugs. Recently, the issue was even broached in the presidential debate in St. Louis.

With both the executive and legislative branches primed, it’s anyone’s guess as to what will happen next. As dysfunctional as Congress has been in the wake of the passing of the Affordable Care Act, shared partisan outrage on drug pricing has policy wonks running to their filing cabinets to rip out new ideas. Regardless of the outcome the over the next several years, it couldn’t be more apparent that the cost of prescription drugs has for the time being captured the gaze of the nation, and with it the gaze of its most important policy makers.

As part of our new policy focus initiative here at GPPR, we want to spend the next several months providing you, the reader, with the information necessary to navigate the complex conversations about prescription drug pricing. Various solutions have been proposed by the Congress, the presidential candidates and a myriad of think-tanks addressing drug pricing including; giving the federal government the power to negotiate drug prices under Medicare Part D, allowing the importation of pharmaceuticals from much cheaper markets outside the US, fixing the FDA approval process, performance-based contracts, value-based frameworks and much more. We want to help you walk through these complicated issues with us. Our hope is that we can learn something together. We warmly invite you to join us in this endeavor.

John Allison is the Senior Policy Focus Editor at the Georgetown Public Policy Review and is a second year MPP student at Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy. He is a proud native of Kansas where he recently completed his undergraduate degree at Kansas State University. His areas of policy interest include health policy and poverty.

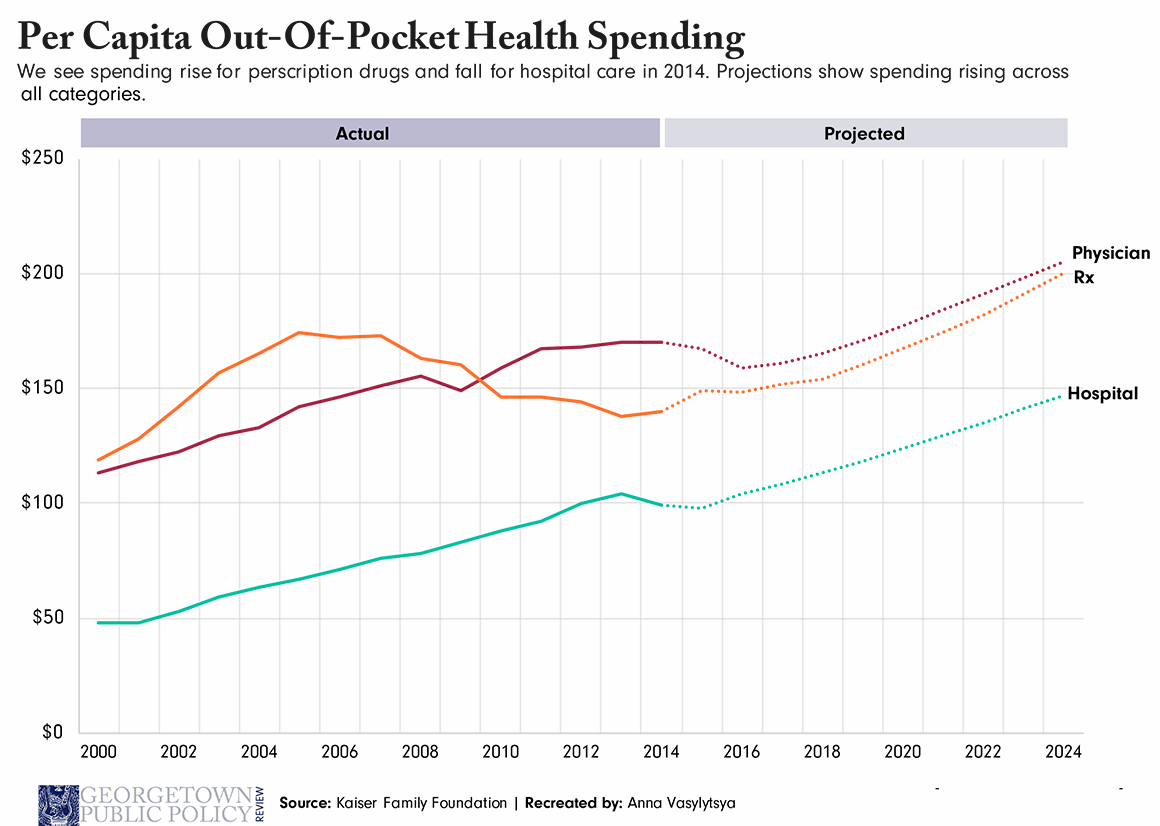

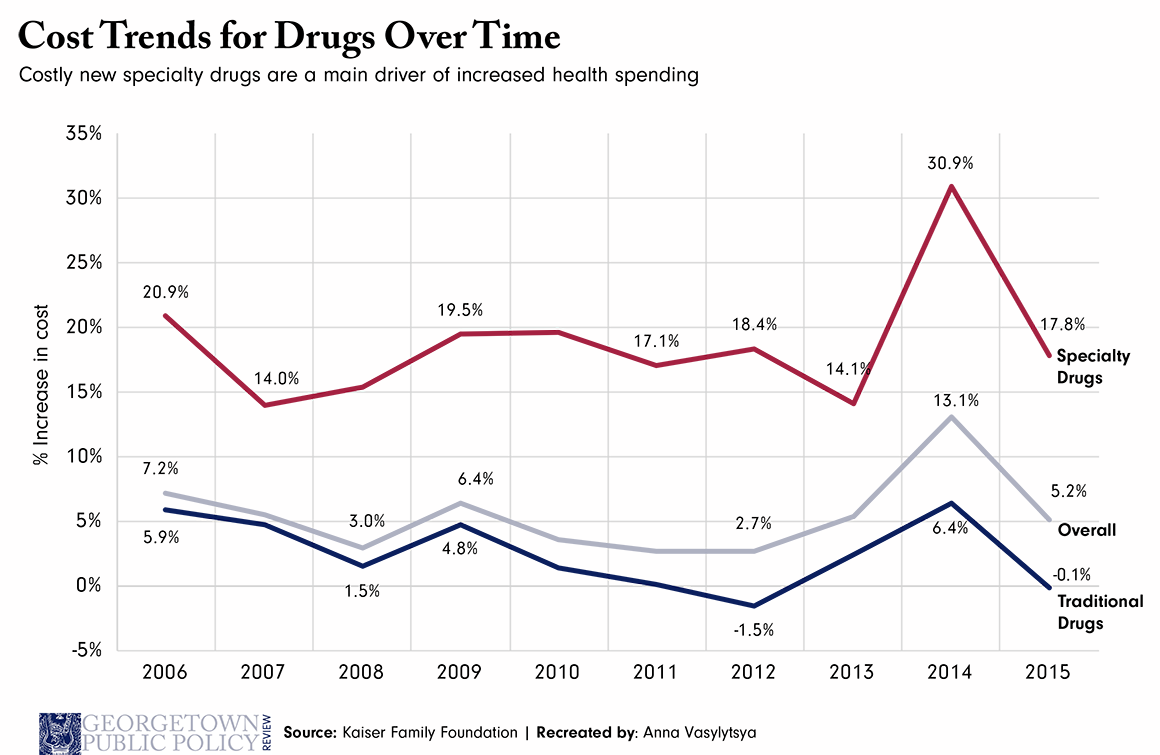

Inpatient and outpatient drugs account for less than 15% of the country’s healthcare spending. Prescription drug spending reduces spending on other healthcare services. Spending on hospitals and physicians is 5-6 times spending on drugs – but as your first chart shows, that difference is not reflected in out-of-pocket spending.

So, is it good public policy to overemphasize “solutions” to prescription drug pricing while ignoring the other 85% of spending? The “gaze of the nation” is easily distracted and may not be a reliable guide to what’s actually important.