Introduction: US Global Competitiveness, the Changing Workforce, and the Case for 21st Century Workforce Policies Growing

Global Competitiveness

Is the United States losing its competitive edge in the global economy? Is the American dream in decline? Are working families still able to make it in America, or are too many left behind? A growing body of research makes these questions poignant for the United States today. According to a recent Pew study, US families are still feeling squeezed since the recession, with over half or 56 percent reporting that their income was falling behind their cost of living in 2014, up from 44 percent in 2007. Middle income families were especially hard hit in the recession with their wealth plummeting from an average of $161,050 in 2007 to $98,000 in 2013. In 2015, the share of US adults in the middle class was surpassed by the upper and lower income tiers for the first time in 40 years, (with 120.8 million adults comprising the former and 121.3 the later). Worse, middle-income Americans’ share of total household income has shrunk nearly 20 percent, from 62 percent in 1970 to 43 percent in 2014. The upper income tier now makes nearly 50 percent of all household income in America. At the same time, real wages have remained stagnant since the 1970s, and despite decreasing unemployment, labor force participation reached the lowest rate since 1978 in 2015.

The Changing Workforce and the Growing Case for Work-Life Policies

Though not a major component of the national conversation on economic competitiveness and the workforce in the past, 21st century workforce strategies—including policies promoting workplace flexibility, work-life balance, and raising the wage—are gaining a foothold in the national conversation. In addition to evidence of strain on the US workforce partly fueling this shift in discourse, recent research suggests workplace expectations are changing along with societal norms and business models. Policies and business practices created when the male breadwinner model was prevalent no longer reflect the current needs nor reality of many American workers or businesses. Working parents, students, and retirees looking to top off their pensions require more flexible work schedules. At the same time, the boom in independent contractors, temporary workers, and the ubers of the world is changing the face of the post-recession economy. All the while, evidence is also beginning to build suggesting work-life policies do not harm economic growth but may actually strengthen it.

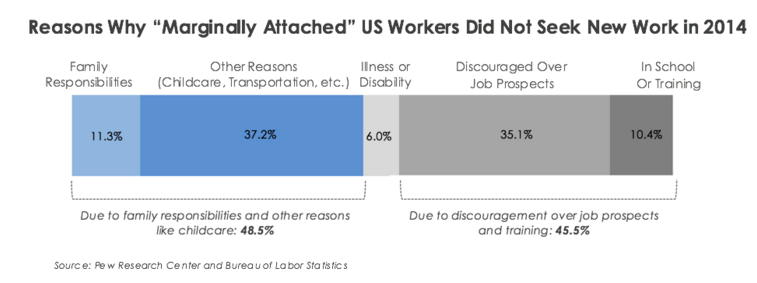

One recent study cited in the Harvard Business Review, demonstrated that the OECD countries with work-life policies—including paid family leave or subsidized childcare—also have lower unemployment. According to the Institute for Women’s Policy Research (IWPR), if women joined the US workforce at an equivalent rate to men, US GDP could increase by 5 percent. The lack of work-life policies is seen as a continuing barrier to employment or advancement for many American women. And it is not just women that could boost the US’s labor force participation rate. More and more young people, between the ages of 16 and 24, are opting out of the workforce according to the Pew Research Center. Why? According to Bureau of Labor Statistics data, of those who looked for a job sometime in 2014 but stopped searching—a group known as “marginally attached” workers—11.3 percent were no longer looking due to family responsibilities while a whopping 37.2 percent had ceased their search due to other reasons including childcare or transportation problems. Together these groups represent an even larger share of marginally attached workers than those who were discouraged about job prospects at 35.1 percent and those in school or receiving training at 10.4 percent.

How the US manages and engages a growing cadre of non-traditional workers, unable or unwilling to meet the old standards of employment, has already begun to impact US economic competitiveness and may very well impact future labor force productivity and economic growth. At a time when the recovery from the latest recession is still fragile, adapting policy to these increasing shifts in worker needs may have a substantial influence on that growth and productivity.

States and Municipalities Rising to the Challenge

With Congress effectively at a standstill and the US still struggling with a mediocre economic recovery, states and localities have stepped up to meet the growing workforce challenge. They are adopting a range of 21st century workplace policies including work-life policies to meet changing workforce needs, ensure inclusive and sustainable growth, and remain competitive in a global economy.

In 2013 alone, 36 states considered 210 bills on various forms of employee leave with 16 states passing legislation. These bills created commissions to study employee leave, expanded benefits, and increased eligibility to include additional family members to name a few. The most common forms of leave discussed and debated across the states include paid sick days and paid family leave (which includes parental leave as well as leave for primary caregivers that are not parents in certain instances). In 2014, the momentum only grew as 14 states passed 22 measures including the second and third statewide paid sick leave laws in California and Massachusetts. Cities and states also considered wage bills, including efforts to raise the minimum wage, in record numbers.

In 2015 states continued to lead the way, with Oregon passing paid sick days legislation and places from Connecticut to Washington, D.C. considering paid family leave proposals. As evidence of the mismatched needs of US workers, businesses and current labor force policies build, states and localities are fueling the pressure on Congress to act. New research demonstrating the detriments to the economy and public health of too few jobs promoting work-life balance combined with the success of state innovations in 21st century workplace policies has strengthened the momentum.

With Growing Evidence of a Problem and the Need for Policy Solutions, States Take Action

Since the recent major economic recession, the spotlight on the mounting struggles of the working class and working families in particular has intensified. With 2014 marking the 50th anniversary since President Lyndon Johnson waged his War on Poverty, many advocates and researchers worry we have not made much progress and, in fact, have fallen backwards. A main contributor to this, they argue, is the accumulation of challenges facing working class families from skyrocketing childcare, education and healthcare costs to diminished wealth and stagnant wages. Together, these factors contribute to protracted financial insecurity and hamper upward mobility even when families are working. So what are policy-makers doing about this precarious state of affairs impacting millions of American workers and US economic stability? States and municipalities across the US are adopting a new brand of employment policies to meet changing demographic needs, ease the burden on working families, and bolster the economy.

Rising Inequality, Poor Wages, and Raising the Wage

Raising the Wage

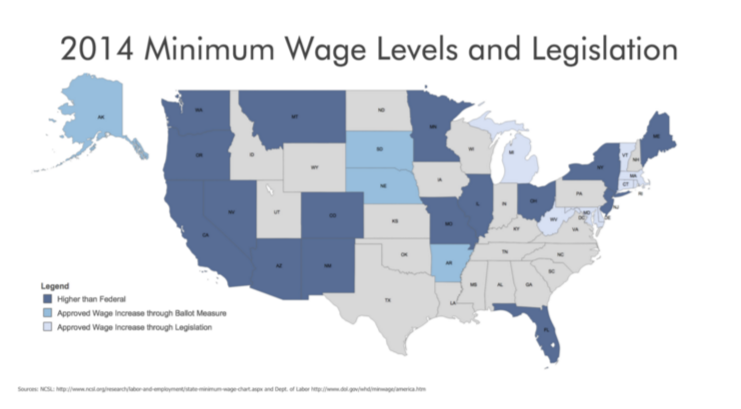

To begin with, states are raising the minimum wage. With the federal minimum wage stagnant since 2009, 29 states have laws imposing a higher minimum wage than the federal government as of January 2016. In 2014 alone, four states passed ballot measures to raise the wage, along with10 state legislatures (11 including DC). Indexed increases also went into effect in 2015 in nine states. This momentum was most evident in Seattle, as the city passed a landmark ordinance raising the minimum wage to $15 an hour, the highest in the US, phased in over several years by 2021.

Rising Inequality and Poor Wages

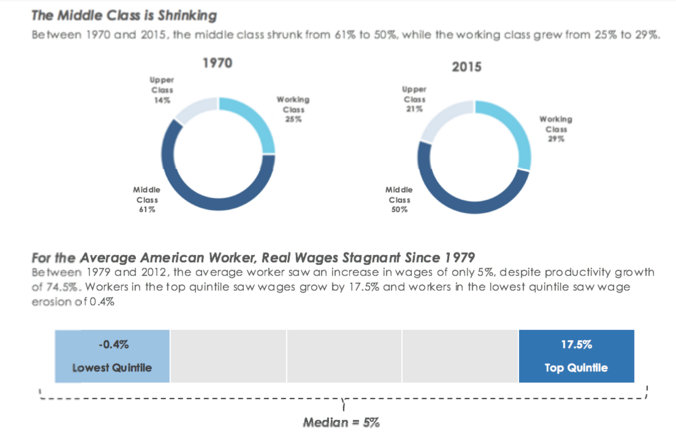

State wage bills have emerged as income inequality remains on the rise, and working families have been falling further and further behind. According to the Pew Research Center, the middle-income tier in America shrunk from 61 percent to 50 percent from 1970 to 2015 while the working class grew from 25 percent to 29 percent. As the middle class shrinks, it becomes more difficult to rise out of poverty and the working class. Only half of those in the bottom quintile ever rise out of poverty while the income of one’s parents predicts a full 40 percent of an offspring’s income upon adulthood. Poor wages are a significant contributor to these trends. Real wages have remained essentially stagnant since 1979 while wages actually fell for the bottom 70 percent of the wage distribution during the most recent recession. In fact, US workers endured a 3.7 percent decrease in real weekly wages since 2000. While the average worker saw an increase of only 5 percent between 1979 and 2012, workers in the top quintile saw an increase of 17.5 percent and workers in the lowest quintile actually experienced a decline of 0.4 percent.

The Expense of Childcare, Bolstering Childcare Subsidies, and the EITC

Rising Expense of Childcare Exacerbates Struggles of Working Families

Exacerbating the stagnant wages of working families, the percentage of single-headed households in the US has ballooned with a fourth of all US households led by a single mom making an average of $23,000 per year. Less than half of US kids now live in a “traditional” home with two parents still in their first marriage. Single-headed households, meanwhile have more than tripled since 1960 from 9 to 34 percent. According to some researchers, these working moms both work longer hours and have more children than their counterparts in other rich countries. The exorbitant cost of childcare too aggravates the problem. Childcare is the single largest household expense in a majority of states (all but the Western states), with average center-based childcare costs exceeding 20 percent of income. Securing childcare is often more expensive, for instance, than rent or housing expenses in the US. Again, this is not only a problem for working parents but their employers and the economy at large. Expensive and precarious childcare arrangements and childcare breakdowns or lapses cost US businesses over $3 billion annually due to employee absenteeism. While all other rich world countries mandate some form of childcare assistance, the US federal government does not and less than 5 percent of US employers voluntarily subsidize or provide childcare support.

Combining all of these stressors, it becomes not only harder to rise from the working class but harder to balance work and family responsibilities while stuck there. A number of current federal policies, including the oft-described “marriage penalty” in the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the benefits cliff effect for families moving from Temporary Aid to Needy Families (TANF) to work, have either contributed to or failed to mitigate these challenges for the working class and working families today. Thus, several states are trying out new policies or refining their regulations to assist parents balancing work and family.

States Bolstering Childcare Subsidies and the EITC

In 2014, bills to help working families afford childcare were passed in five states: California, Colorado, Minnesota, Nebraska, and Rhode Island. Legislation in California, for instance, raised childcare subsidy income eligibility caps and provider reimbursement rates. Similarly, Nebraska passed new rules discounting 10 percent of a household’s gross income towards their eligibility. By the end of 2015, three states including Utah, Colorado and Idaho had enacted Pay for Success legislation to fund early childcare based on quality.

Also in 2014, six states and DC enacted EITC-related legislation, mostly to increase their EITCs. That number rose slightly to eight bills in 2015. State EITCs first emerged in 1987 with Maryland, and now 26 states and D.C. have state-level EITCs. Without state EITCs, the number of states taxing single moms and married couple families below the poverty line would roughly double, from 11 to 21 and 13 to 26 respectively. Thus, like affordable childcare, these tax credits are significant tools to prop up working families, especially hourly wage earners, as the economy continues to squeeze the working class.

Family Leave in the States

States Introduce Paid Family Leave

In addition to raising the wage, childcare subsidies and EITC tweaks, more explicit work-life policies have moved to the fore in several states in recent years as paid family leave legislation, also called paternity leave, has gained traction. The United States is only one of eight countries—and the only high-income country—that does not mandate paid maternity leave. At the same time, 81 countries, not including the US, provide some paid family leave specifically for fathers. Without such public policy, only 13 percent of US workers have access to paid family leave sponsored by their employers. In the bottom quartile of workers, only 5 percent receive such a benefit. While other countries have drastically changed policies having witnessed their populations decline and dip below replacement rate, the constant flow of immigrants into the United States has partly shielded the US from the consequences of failing to promote family life in the rich world.

After the year 2000, the US began to catch on to the global paid family leave trend, passing legislation at the state level. Most recently, Rhode Island passed a bill in 2013 allowing up to four weeks of paid family leave time. The new law, implemented in 2014, provides for a wage replacement rate of 4.62 percent. The weekly benefit rate in 2015 ranged from a minimum of $84 up to a maximum of $795. Importantly, the bill also establishes job protections, requiring employers to guarantee the same or an equivalent job upon return from leave.

Two other state laws, in California and New Jersey, preceded the Rhode Island law. California passed paid family leave legislation in 2002 by expanding its Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) to include paid leave for up to 6 weeks. The law went into effect in 2004 and in 2014 it provided up to about 55 percent of earnings capped at $1075 per week. The coverage is financed entirely by employee payroll taxes with no direct cost on business. New Jersey passed its paid family leave law in 2008, also providing up to 6 weeks for newborn or adopted child leave. The insurance program covered two-thirds of weekly pay up to $595 per week in 2014 for employees on such leave. Like the California law, this law is funded entirely by the payroll tax. Unlike the Rhode Island bill, the New Jersey bill does not guarantee job retention.

The only other state to date to have passed paid family leave legislation was the state of Washington. Though passed in 2007, the bill’s implementation stalled indefinitely as its funding mechanism was left undetermined and, eventually, it was repealed altogether.

All of the states which have passed family leave legislation have done so through expanding existing temporary disability insurance programs. Only five states have created TDI programs, beginning with Rhode Island back in the 1940s. The remaining two states having passed TDI legislation but not an explicit paid family leave bill include Hawaii and New York. Both of these provide some coverage for disability leave due to pregnancy or, in other words, maternal leave. Several more states are considering paid family leave legislation with proposals put forth in Massachusetts, Connecticut and DC in 2015.

Unpaid Family Leave Expansion

Though only a few states have passed paid family leave measures, several others have taken steps to improve unpaid leave opportunities. California, Connecticut, D.C., Hawaii, Maine, Minnesota, New Jersey, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, Washington and Wisconsin have all passed legislation related to family leave. Most of these have expanded either the amount of leave available or the classes of persons for whom leave may be taken. For instance, Maine expanded upon federal maternity leave regulations, only encompassing businesses with 50 or more employees, to include employers with as few as 15 or more employees. Vermont similarly expanded responsibility to employers with 10 or more employees. Shortcomings of federal leave laws—also not passed until relatively recently in 1993—have spurred other states to make similar variations.

School Leave

While paid leave for family or health reasons has been the dominant form of legislation amongst 21st century work-life policies in the US in recent years, states and localities have also led on several other work-life initiatives and working class family policies. Several states, for instance, have set laws specifically allowing parents to take time off work for school-related reasons such as to see a child’s play or attend parent teacher conferences. While California provides the most time off for such school leave, at 40 hours, North Carolina provides the least at four hours. Of the nine states including the District of Columbia that provide school leave, the average allotment is a little over 17 hours. In an alternate approach to permit parents time for their kids, Nevada makes it unlawful to terminate an employee for using leave to attend a child’s school-related activities.

Paid Sick Days at the State and Municipal Level

The Case for Sick Days

While paid family leave laws have gained traction, so too has momentum grown in support of supplying workers paid time off when they are sick. Forty-five million workers in the United States work without paid sick days. On average, 40 percent of US workers have gone without paid sick time in recent years and that number is declining. While 37 percent of low-wage workers had access to paid sick time in 2009 only 34 percent did in 2014.

While such statistics in themselves may not be alarming to many, these workplace policies have an array of consequences on both the economy and in other realms like public health. Paid sick days are least likely to be found in the construction, hospitality, and food service industries. In some states, paid sick time is also most uncommon in the social services, healthcare, and education fields. Many of these are the same fields in which employees most commonly come in contact with the public, heightening exposure and potentially endangering some of the most vulnerable populations such as children and the infirm.

In one nine-state study, for instance, researchers found that in a single year 20 percent of food workers came to work vomiting or experiencing diarrhea. In another case, 100 people were found to be infected by just one sick food worker in Michigan. By contrast, those with paid sick time were 28 percent less likely to be injured on the job, according to the US Department of Labor. Workplaces encouraging a “flu day” experienced a 25 percent decline in the spread of flu through workplace transmission and a 40 percent decline for two flu days states a University of Pittsburgh study. Without paid sick leave, parents are also sending their children to school sick, exposing many other kids to illness. An IWPR report found that amongst all workers with access to paid sick leave only 30 percent may use their leave to care for sick children.

In addition to obvious public health concerns, a lack of paid sick days can impact productivity and employment, as employees come to work sick and cannot focus or put their jobs in jeopardy by failing to show up. Add these burdens associated with health and family life to stagnant wages and low economic mobility, and the picture of millions of American families living constantly on the brink becomes clear. As last year’s Shriver Report put it, “Forty-two million women, and the 28 million children who depend on them, are living one single incident—a doctor’s bill, a late paycheck, or a broken-down car—away from economic ruin.”

Momentum Builds for Paid Sick Days in States and Cities

Like with paid family leave, paid sick leave legislation has been on the rise to meet these challenges, especially since the most recent recession. The first city to pass a paid sick days ordinance was San Francisco in 2007. The law provides for one hour of earned sick time for every 30 hours worked up to 40 hours for businesses with less than 10 employees and 72 hours for bigger businesses. This basic framework established in San Francisco has become the model for sub-national sick leave legislation. Connecticut was subsequently the first state to pass paid sick leave legislation in 2011. These firsts set the precedent for other cities and states facing similar workforce challenges and debating the merits of paid sick time legislation. In particular, the fear of negative consequences for businesses was tested in these two arenas, enabling other states to proceed better informed.

2014 saw the number of state paid sick leave laws triple, with California passing legislation and Massachusetts residents winning a ballot initiative with the support of 60 percent of the voters. In 2014, cities across the US also advanced the paid sick leave agenda with the cities and towns of Paterson, Passaic, East Orange, Jersey City, Trenton, Irvington and Montclair passing ordinances in New Jersey, while Eugene, Oregon and Oakland, California, also enacted earned sick days ordinances. These cities were preceded by ordinances passed in 2013 by New York City, Jersey City, Newark, Seattle, and Portland, Oregon. In 2013, Washington, DC also expanded its 2008 law.

In 2015, Oregon was added to the list of states with paid sick days laws as were the cities of Tacoma, Washington, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, Bloomfield, New Jersey and Emeryville, California. Also in 2015, Montgomery County, Maryland became the first county in the country to establish a paid sick days standard. It is no longer just the coasts taking the lead on sick days either. The momentum continues to grow with at least 20 states from Arizona to Louisiana to West Virginia now considering paid sick leave legislation.

Other Supports for Working Families

Taking a Comprehensive Approach

Beyond regulating paid and unpaid employee leave as well as subsidizing childcare and wages, states have implemented several other strategies to prop up working families. Some states have targeted their 21st century workforce policies specifically to uplift women, recognizing the disproportionate number of single moms as well as the lower incomes of working mothers. Strategies have extended as far as equal pay promotion—historically a policy area debated primarily amongst elites—but increasingly relate to and focus on working families.

The Minnesota legislature, for example, passed the Women’s Economic Security Act in 2014. The comprehensive bill addresses a wide range of challenges related to being a woman—especially a parent or guardian—in the workforce. Though advocates did not succeed in including every desired item in the final bill, major components of the bill that did pass included extending eligible use of paid sick days to non-nuclear family members, lengthening unpaid maternity leave, ensuring compliance of state contractors with equal pay regulations, prohibiting discrimination and enforcing workplace protections for nursing and pregnant employees, raising the minimum wage to $9.50 by 2016, increasing the availability of early child care scholarships with an added $4.65 million, and providing funding for women owned businesses and centers. While many of these items strengthen existing laws, the coalition is gearing up for several wholly new advancements. Their agenda includes ensuring paid earned sick time for all Minnesotans, creating a family leave insurance program providing wage replacement to new parents, and eliminating childcare waitlists as well as expanding childcare tax credits to middle-income families.

Minnesota’s multi-pronged approach founded on extensive coalition-building has recently been effective in other cities and states across the US as well. For instance, the success of measures in Seattle, Oakland, and Massachusetts relied upon coalitions built around the minimum wage and paid sick time. City, state, and community leaders are also turning to their counterparts across the country for advice, technical assistance, and as promotional partners with positive models to be replicated. As momentum builds across the states, the national conversation is shifting and evidence has and will continue to build as to these new measures’ effectiveness.

Addressing Changing Labor Force Realities including the Growing Temporary Workers Industry

While established industries attempt to adjust to the changing workforce and cities and states try to bolster policies responsive to the shifting needs of working Americans, elected officials are also beginning to consider a new type of legislation for emerging industries. Thanks to a combination of new technology, recession business planning and shifting worker needs, temporary work has exploded in the US. By May 2015, temporary workers accounted for 2.4 percent of private sector jobs in the US. A whopping 40 percent of workers are contingent. As opposed to secure full-time positions, these workers are on-call, contracted or part-time. Little has yet been done to specifically regulate the growing field of independent contractors, temporary workers and other non-traditional workers such as Uber drivers as states are just beginning to recognize and grapple with the unique challenges of these rapidly emerging industries.

The private sector has taken differing approaches to protect and promote these new business models. At the same time Uber pushes for policies enabling its legal entrance to serve cities and states across the US, the staffing industry has opposed introducing new legislation or regulation particular to temporary workers. As these workers often fall into a loophole in which they do not qualify as employees or independent contractors, they are not protected by current labor laws nor entitled to related benefits. As such, concern grows amongst advocates as reports of abuse increase and the opportunity for abuse widens with the rapid expansion of this newly normal type of labor. To begin addressing this worry, Massachusetts passed legislation in 2012 to ensure temporary workers, at a minimum, are provided documentation informing them in advance of the wages they can expect, any protective gear required, and the name of the responsible firm if an injury should occur. The bill also limits fees imposed on temporary workers for drug screening, criminal background checks, and payment methods such as bank cards. New Jersey and Illinois passed similar legislation. In 2014, California followed suit with its own legislation designed to better hold companies legally responsible if the staffing agencies or other sub-contractors they hire abuse their workers. As this temporary type of work proves to be a new normal rather than a recessionary trend, more states are likely to join them.

Early Effects of State and Local Policies

Though still early and limited to a small number of case studies, evidence is beginning to build around the efficacy of state and local policies designed to meet the needs of working families and promote workplace practices befitting the modern economy and our changing society.

Paid Sick Leave

Some of the earliest evidence from San Francisco’s breakthrough paid sick time ordinance provided fodder for other activist cities and states. For instance, in San Francisco, the feared burden to businesses and deterrent to employment did not materialize for measured indicators. According to IWPR, employment growth remained stronger in San Francisco during the years after the recession, both overall and within the food and accommodation industries, which are most likely to be impacted by paid leave legislation. There was only one exception in which the food and accommodation industries in San Francisco experienced a greater dip in employment of 5.2 percent as compared to 4.5 percent in surrounding localities between 2008 and 2009.

At the same time, in a survey of 1,200 employers after passage of the ordinance, six of seven said they experienced no negative impact on profitability. Moreover, 50 percent of employees said they benefited from the ordinance. Finally, concerns that paid sick days would be abused or over-utilized did not materialize as the average worker used only 3 sick days and 25 percent did not use sick time at all.

Whether all of these findings are relevant to other localities is questionable. San Francisco has long been an employment hub with many industry headquarters. As such, the city may be more resilient to the negative consequences of such an ordinance than smaller communities without such magnetic economies including those compared to it in this study such as Alameda, Santa Clara and San Mateo.

Though initial concerns over transferability remain relevant, the evidence in support of paid sick leave is growing as additional localities and states enact legislation. In Connecticut, the first state to pass paid sick time legislation, two thirds of businesses surveyed said they experienced no or less than a 2 percent cost increase due to the ordinance. In fact, according to the Center for Economic & Policy Research, a year and a half after passage in Connecticut, more than 75 percent of employers surveyed expressed support for the new paid sick days legislation. For these, it imposed little to no cost as well as minimal administrative burden while boosting morale and reducing workplace illness in many cases. Coverage in the state expanded primarily for employees in the health, education and social services industries as well as the retail and hospitality industries. Part time workers also disproportionately benefited as many full time employees working for firms with 50 or more employees were already covered. As a result of the law, less than one percent of employers reported reducing wages while only 10.6 percent reduced employee hours, 3.4 percent reduced operating hours and 1.3 percent suggested they reduced the quality of their services. Moreover, nearly 85 percent of those surveyed said they did not increase prices to consumers due to the ordinance.

Despite these positive findings, the field of research on paid sick days is not yet robust, as the number of studies is limited. Moreover, most have been conducted by supportive think tanks and advocacy groups. One meta-study conducted by the conservative Freedom Foundation reviewing all the major research to date notes that most studies exaggerate the decline in workers showing up sick and the reduced turnover while not properly accounting for increased prices, reduced profitability, and the effect of such legislation on curbing expansion. Furthermore, the study suggests, most proponents neglect to highlight that a majority of businesses affected already offer paid sick time.

Despite the somewhat contested findings, the limited amount of research to date, and the minimal effects established of paid sick leave policies, momentum is building across the states as the benefits for workers are demonstrated while the feared consequences for firms are found to be minor or negligible.

Paid Family Leave

While also not definitive, the evidence supporting paid family leave is promising. Researchers have cited increased labor force participation and decreased spending on public assistance on the macro-level while increases in family incomes and improvements in employee retention reducing reduces business costs have also been found.

One of the major factors contributing to all of these positive effects is the suggested labor force attachment effect of providing paid family leave. This effect induces mothers to continue to work rather than leave the workforce altogether. From a meta-study conducted by IWPR, research shows that women are 40 percent more likely to return to work if offered paid leave and 69 percent more likely to return after 12 weeks of leave than their unpaid counterparts.

Though, once again, conclusive research is not available, some evidence also indicates that it is more costly to employers to hire new employees rather than retain parents after leave. One survey of 621 Connecticut businesses found that 25 percent of employers replacing managers and 16 percent replacing clerical workers took over six weeks to find new employees. As most paid leave is six weeks or less, the added cost and administrative effort to replace an employee on leave may not be worth the trouble for employers. Replacement costs, studies have shown, can range from $2,000 to $14,000 and usually fall between $4,000 and $9,000.

Retaining employees in the labor force that may otherwise drop out due to familial responsibilities, economists argue, is also beneficial to the overarching economy as productivity and earnings rise. Those employees retained in the labor force also avoid reliance on government assistance programs that are already strained. Nearly 10 percent of women receive public assistance when on unpaid federally mandated (FMLA) leave. The government spends $413 less in public assistance for moms with paid leave as compared to those with unpaid leave in the first year after birth.

Beyond labor force retention benefiting the entire economy as well as individual businesses, some research has indicated that there are also less substantial costs to businesses than opponents suggest. In one survey of California’s paid family leave law, 89 percent of employers said that there was no or a positive effect on productivity while 87 percent reported no effect on cost. Moreover, 98.8 percent said that they actually experienced a positive effect on costs as the new insurance provided by the state relieved some of the employer burden of benefit provision.

Finally, benefits to public health and, by extension, the economy through reduced medical costs, result from paid family leave. In the case of California, for instance, moms that took paid leave after the ordinance passed breastfed twice as long as moms that didn’t take leave. Paid family leave is also associated with a 9 percent to 10 percent reduction in infant mortality in one international study.

While not as much research has been conducted opposing paid family leave, some industry groups do suggest the consequences could be significant for the economy and specifically the low-wage workers intended to benefit most from legislation. A research study by the National Federation for Independent Businesses, one of the most extensive associations of businesses and small businesses in the US, suggests that between 12,000 and 16,000 jobs could be lost over several years if paid family leave is mandated, not to mention billions lost in economic output. Others argue that citing other nations’ seemingly successful programs can be misleading as unintended consequences of “mommy tracking” may not be accounted for: though women may remain in the labor force, they argue, they may be less likely to rise to leadership positions thanks to generous maternity leave policies.

Considering the available research then, definitive answers on the costs and benefits of paid family leave remain elusive. There are both potential economic costs in terms of jobs, hours, and advancement as well as benefits such as labor force retention, reduced attrition, lower healthcare costs and higher incomes over the lifetime. Adding further confusion, paid family leave may have both positive and negative effects on the same economic indicators and targeted populations. For instance, while income may rise due to labor force retention, it may also fall due to “mommy tracking.” Similarly, while new benefits of paid sick leave go primarily to those populations currently without voluntary employer coverage—disproportionately black, Latino and low-income—these populations are also most vulnerable to job and hours cuts due to the legislation.

Thus, only more time may tell the true benefits of paid leave policies in the United States as more data on fertility rates and infant mortality as well as female labor force participation, non-traditional workers as a share of the population, and the mobility of working class families may be collected. Longitudinal studies weighing all relevant factors against one another as new states and localities pass legislation will help clarify the case. Until then, weighing the suspected costs and benefits of paid leave and other work-life policies in context of current economic trends and projected needs may best determine their utility. For instance, arguments for paid leave may be bolstered by the current downward trend in labor force participation that such policies serve to counteract.

Other 21st Century Workplace Policies

Like paid leave, other 21st century workplace policies remain contested. Economists are divided as to whether and to what degree marginal minimum wage increases harm job creation as they lift some families out of poverty. Similarly, equal pay legislation and other such policies preventing discrimination against women, pregnant and nursing employees, and mothers have been called both costly to firms and minimally disruptive while having a yet unclear effect on women’s pay and advancement. Finally, weighing the costs and benefits of subsidized childcare remains unsettled. While some promising results have stemmed from research illustrating short and midterm economic benefits of Headstart and universal pre-kindergarten in Oklahoma, for example, the extensive costs of such programs have not been proven worthwhile over the long term with few demonstrable lasting effects.

With many factors contributing to outcomes in each of these policies areas, it may take more comprehensive approaches such as Minnesota’s to demonstrate sustained and significant benefits of policies propping up working families and promoting 21st century workplace practices. Luckily for data analysts, more and more states continue to take the lead in passing work-life policies. They are fine-tuning legislation based on past successes and failures and implementing pioneering strategies to bolster their economies while meeting the needs of their changing demographics. With these labs of innovation busy at work while national policy continues to stall, researchers will likely have more answers in due time. Until then, the substantial economic pressures on working families combined with the promising early results of state and local 21st century workforce policies will continue to spur more cities and states to act.

Continuing Issues and Challenges to Tackle

As the discussion on the early effects of state and local 21st century workplace policies suggests, there is much work left to be done to create policies that better fit our changing labor force and keep the US competitive in the global economy. Existing work-life policies and other state-led efforts to shore up working families are not exempt from this challenge. From ensuring the policies reach their intended purposes and populations to mitigating negative consequences on firms and employees, states have been identifying problems and proposing amendments to fine-tune their laws.

First, states have identified several ongoing challenges with their workforce policies, particularly paid leave initiatives. Access to paid leave for non-traditional families—including guardians who are grandparents, siblings, and adopted families—was initially limited in several states’ laws. California has since updated its law to incorporate such families. Another overlooked aspect of new employee leave laws has been guaranteeing job protection upon return from leave. While earlier states did not provide such protections, later iterations, such as Rhode Island’s family leave law, do explicitly include job protection. Finally, as most states primarily provide partial wage replacement, the pay rate may not be high enough to enable low-income families to forego work. This likely impacts the lowest income, immigrant, and minority workers most—the same populations considered by many to be the greatest in need of such policies.

A second major issue is awareness. Awareness of the new paid sick days and paid family leave laws has been shown to be highest at large firms. Many of these already provide some such benefits as compared to smaller firms where the new benefits may be most impactful. For instance, half of California’s benefits under the new family leave law were used by employees of firms with 1000 or more employees though they only comprise 14 percent of the workforce. Awareness and use was also lower amongst low-wage women and people of color. Immigrants too are a sub-population more likely to benefit but simultaneously less likely to be aware of such legislation. Similarly, new legislation to protect temporary workers is only useful if the workers are aware of their rights and the laws are enforced. States and localities are only beginning to grapple with how to best enforce these laws as well as promote and provide equal access to all potential beneficiaries.

Paid employee leave laws are not the only ones amongst 21st century workplace policies in need of adjustment and improvement. Advocates argue that state EITC laws must remove penalties and disincentives for married couples as well as carve out special allowances for new moms. Meanwhile, proponents of improved childcare policies are devising new means to increase access and quality. States from Massachusetts to Minnesota are considering legislation to increase funds for government-sponsored childcare, expand eligibility for childcare subsidies, and improve payment rates for childcare workers.

In addition to tweaking existing legislation and ensuring it reaches those intended, there remain additional challenges yet to be tackled in aligning policy to today’s economic reality. Opportunities largely untapped by policymakers include envisioning new strategies to work with or directly involve businesses to craft a better work-life balance in states across the US. Harnessing new and alternate methods such as telework may be one such opportunity ripe for collaboration. Confronting more nuanced problems such as the economic security of hourly workers most vulnerable to rapid schedule changes and lacking full benefits coverage similarly remains an area largely untouched. Fitting work-life models and policies to non-standard jobs and hourly workers may be a rising challenge for coming generations as the US economy continues to shift towards the service sector and technology enables more freelance employment.

Finally, as states and localities continue to make progress on 21st century workforce policies, several others are working to combat these changes. For instance, 11 state laws have passed pre-empting local paid sick time ordinances, eight of which passed since 2013. Proponents cite the need to protect small businesses from undue burden and maintain regulatory consistency across the state. As momentum builds around work-life policies, so does the backlash and continued need to mitigate unintended consequences.

Will the Federal Government Follow Suit?

With the near-feverish activity at the state and local level, the question remains, will the federal government follow suit to address changing economic realities and shore up working Americans and their families? In major news this year, the Pentagon announced that it will institute 12-week paid maternity leave across the armed forces in addition to several other new initiatives including expanded childcare to retain female service members. Elected officials at the federal level, meanwhile, have not passed as significant work-life legislation since the 1993 Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). The federal minimum wage has not been raised since 2009. Nonetheless, Congress and the White House have begun to take notice as the buzz builds in states and localities. President Barack Obama cited state leadership on the minimum wage in his State of the Union Address in 2013 and on paid sick time in 2015, calling on Congress to act. In his 2016 address, the President promoted paid family leave. With growing attention on the struggles of the modern American worker, President Obama hosted the White House Summit on Working Families in the summer of 2014. Beyond taking supportive stances, the President also signed an executive order requiring all new federal service contractors to provide wages of at least $10.10 an hour and another order granting federal workers six weeks of paid family leave.

In 2013, members of Congress including Representatives Kirsten Gillibrand (D-NY) and Rosa DeLaura (D-Connecticut) introduced the FAMILY Act to provide paid family leave and sick time to employees through an insurance program housed within the Social Security Administration (SSA). The House and Senate have also seen a number of minimum wage bills introduced in recent years. However, none have succeeded since 2009, with the Senate failing to pass legislation by six votes in mid-2014. Despite these recent calls to action and symbolic gestures, major or comprehensive action at the federal level is not likely any time soon. It will remain upon the states and municipalities to develop innovative ways to ensure economic growth and opportunity including for working families.

The Future of the American Workplace

States and cities across the United States are leading the way in adopting 21st century workforce policies that ease the financial burden on working families, protect vulnerable new classes of workers, and better address the needs of the changing demographic of American workers. However, as momentum builds around wage, benefits and work-life policies, so do detractors. Opponents rightly point out robust proof is not yet available showing that the benefits of such policies outweigh the costs. Even if somewhat limited, the evidence supporting 21st century workplace policy is positive and promising on the whole. Perhaps more importantly, state and local innovations to date have largely disproved fears that such legislation will have dire consequences on firms as well as working families.

Cities, municipalities, and states across the US still have much to do to reach the intended goals of such policies as access to and awareness of the benefits of these laws too often lag initial passage. Moreover, policymakers face both new and unaddressed challenges of mismatched employer standards and employee realities, as well as outdated laws irrelevant to today’s and tomorrow’s workplaces. They must go beyond available frameworks to meet these emerging needs.

It is now crucially important to evaluate workforce and employment policies as the US workforce, family structures, and labor practices continue to shift at the same time positive economic indicators such as labor force participation are dipping, economic mobility declines, and the US struggles to remain competitive in a global marketplace. With federal action unlikely anytime soon, states and localities will continue to lead the way in innovating to meet the challenges of the 21st century workplace. As evidence continues to accrue and momentum builds, these early state and local pioneers may just influence a sea change in US workforce and employment policies yet.

Stephanie Keller Hudiburg is a recent graduate of the McCourt School where she focused on community and economic development policy, public sector innovation, and performance management as the Co-Director of the McCourt School Policy Innovation Lab and a Research Fellow with the Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership. Before moving to DC, Stephanie served as the Chief of Staff to a State Senator representing Boston in the Massachusetts Legislature. She is now the Director of Programs and Partnerships at The Real Estate Council in Dallas. Stephanie is a state and local policy enthusiast, writing on several related innovations and reforms for this series.

So do links from LinkedIn and Tumblr now contribute for search engine optimisation? I was told they help because of the Penguin Google algorithm refresh

Posted this to Twitter, very interesting