Why are some countries rich and other countries poor? From Plato to Adam Smith to the Simpsons, the best and brightest have wrestled with this question. In a new working paper, “Malaria and Early African Development: Evidence from the Sickle Cell Trait,” presented at the Georgetown Initiative on Innovation, Development, and Evaluation (gui2de) seminar series, Brown University’s David Weil investigates how levels of malaria since the year 1500 may have affected economic growth in the past. Understanding how societies dealt with this deadly disease could have implications for growth today. Using the prevalence of sickle cell anemia (which provides some immunity against malaria) derived from historical records, Weil and co-author Emilio Depetris-Chauvin, a PhD candidate at Brown, estimate malarial severity to create an index for the malaria burden in the past. They then model its impact on development in sub-Saharan Africa, the region with the highest prevalence of malaria today. This historical-genetic-economic approach to a question that has perplexed economists since The Wealth of Nations is a novel attempt to add further perspective to increasingly divisive growth theory research within the discipline.

Research suggests that past development predicts present development, but there is disagreement on how this plays out in answering, “Why are some countries poor?” One side of the debate identifies geography and culture as key factors in past growth, which affects the world we have today. For example, if you live an area where disease hindered development in the past, the area is likely to still be underdeveloped. Jeffrey Sachs and Jared Diamond are two of the best-known proponents of this view. Others contend that the factors affecting past growth, like geography or disease, are not necessarily relevant today. Rather, they could have an impact on current underdevelopment through separate means. Why Nations Fail authors Daron Acemoglu and James Robinson are famous for their exploration of whether or not disease kept large numbers of colonists from moving into an area and developing it.

Weil and Depetris-Chauvin take a step back from this debate to figure out what the malaria burden would have been in 1500, which, regardless of a causal story based on geography or colonists, could affect the future outcomes that these theories rest on. For David Weil, this area of research is familiar ground, but combining sickle cell, historical, and economic growth data was new. “The understanding of how sickle cell can be used as an indicator for the severity of malaria is pretty widespread among economists who work in this area—and of course is well-known by doctors and biologists,” Weil explained. “So the only thing that I did was integrate that understanding into a more quantitative setting” to determine past malaria burden and test for any effects on growth. As gui2de co-founder and McCourt School Associate Professor James Habyarimana notes, “The very clever research design exploited in this paper is a nice way to shed light on the controversy around whether there are direct effects of geography on prosperity (as in Sachs) or if the effects operate through institutions (as in Acemoglu et al). Proponents of the direct effects channel have singled out malaria as an important case. And rightly so, as it undoubtedly accounts for a large share of the disease burden. So this paper is right in the middle of this debate.”

Understanding the Threat of Malaria

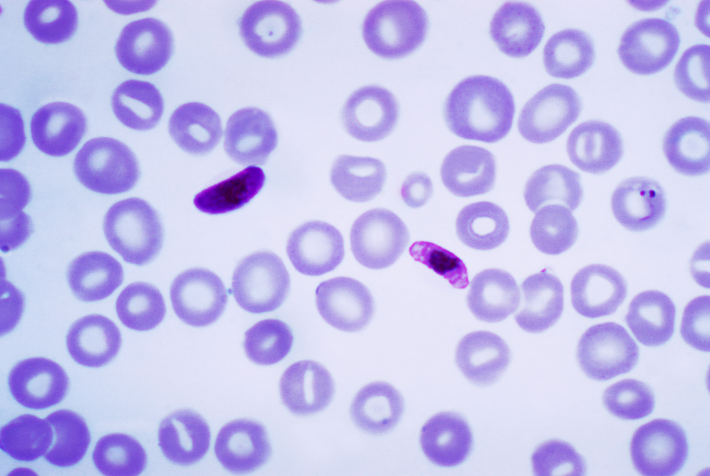

Malaria has long been associated with under development. The disease continues to decimate low- and middle-income countries, with 90 percent of malaria deaths occurring in Africa. The sickle blood cell mutation is widely seen as a genetic adaptation in areas with high rates of malaria. The sickle cell trait is the result of an abnormal S hemoglobin in blood cells that causes the normally disk-shaped cells to become crescent shaped. Carriers of the S trait, who have both a normal A hemoglobin and an S hemoglobin, are often able to withstand the effects of malaria as some of their infected malarial cells sickle and are destroyed by the immune system. However, people with two S genes (homozygous individuals for those who remember AP biology) often have health complications if they survive past childhood. Weil and Depetris-Chauvin use a historical geo-database of S gene frequency from another recent paper to estimate the prevalence of malaria, under the general assumption that sickle cell mutations are a response to high malaria prevalence. The authors use the database to estimate the probability of an S trait carrier surviving to adulthood relative to non-carriers. The larger the ratio of the two probabilities, the bigger the benefit to being a carrier. Through this, Weil and Depetris-Chauvin are able to create a measure of the past malaria burden, which assumes the actual impact of malaria on an area.

To check their results, the authors use current data on sickle cell anemia among African Americans using the same probability model, and achieve fairly accurate results: they estimate 7.9 percent of the population would be carriers, when in fact it is 8 percent. In their paper, the authors are able to use ethnic and geographical data to map their new malaria burden measure onto sub-Saharan Africa. Although the prevalence of the sickle cell trait is exogenous, or generally un-related to other factors affecting growth, Weil notes that historical data can be tricky to use. “[E]ven if it has a lot of measurement error in terms of explaining differences in malaria rates at different points on the map,” Weil explained, “I think that our burden measure is useful in getting an estimate of what the burden of the disease looked like in the pre-colonial period, which is something that I find interesting in and of itself.”

Does Disease Affect Development?

Rather than focus on income growth, as is common in related literature, this new research empirically tests the impact of malaria on development by looking at population density, specifically the ethnic make-up of sub-Saharan Africa. Interestingly, the regression analysis done by Weil and Depetris-Chauvin finds that across the region’s diverse ethnic make-up, areas with high malaria burdens are more likely to have high population density, prosperous local communities, and complex settlement patterns. One explanation for this, as the authors explain, is “malaria deaths are relatively low cost,” in that the amount of resources a community has invested in a newborn is low compared to an adult that has been educated, trained, and so on. In areas with a high malaria burden, the sickle cell trait will kill off some, but those who simply carry the gene, the A-S group, will likely live to adulthood to become trained, educated adults, which could explain why the malaria burden is not negatively associated with development.

One reason the quest for explaining growth has remained so elusive is the difficulty of actually accounting for everything that could matter in the development process. Life is complex, history is messy, and data are not always available, accurate, or consistent. “Relying on historical population data, as well as imputing ethnic-level sickle cell gene prevalence, is a cocktail for attenuation bias and/or large standard errors,” according to McCourt Professor Habyarimana. That is, any estimates the research makes will likely be off, and probably will under-estimate the effect of malaria, because the historical data record is so uncertain. Weil and Depetris-Chauvin recognize the murky waters into which they wade and temper their ambitions to simply note whether there are any correlations between the malaria burden they have estimated and measures of development. Weil explains that, “[a]ttenuation bias is one reason why the empirical parts of the paper (finding no significant effect of malaria burden on outcomes) cannot be taken as definitive.” Yet, there is still value in testing the malaria burden on historical data as it could provide more accurate or different results compared to other attempts to estimate the disease landscape. “I think that the best we can say is that we are bringing a new measure to the table, and that maybe the measurement error in this one is unrelated to measurement error in other indicators (like malaria ecology).”

We know the ravages of malaria in parts of sub-Saharan Africa today. What this research attempts to find is the impact of the disease in the past. The authors find that in areas with a high prevalence of malaria, about a fifth of the population have the sickle cell gene, with about 11 percent of children dying from the sickle cell trait or from malaria. However, by going as far back as 1500, the authors also find that the death rate was almost twice as high in the past. In their modeling, the authors discover that despite such a high death rate, there was little to no negative impact on economic development, mostly because many of the deaths were among young children who couldn’t contribute to an area’s development and in whom limited community resources had been invested relative to adults. This doesn’t necessarily explain why countries in West and Southern Africa are poor today, but it does shed light on the fact that even though life was clearly more difficult, with a higher disease burden, it did not result in economic stagnation. People are resilient. Investigating 500 years of sickle cell prevalence could suggest that development proceeds apace human adaptation. Why some countries are rich and others are poor remains an open question, but the burden of malaria in the past, before colonization, may not be the culprit.

Jacob Patterson-Stein is a second year Master of International Development Policy student. Prior to attending McCourt, Jacob worked for Thomson Reuters in Washington D.C., the More than Me Foundation in Liberia, and in a rural public school in South Korea. He spent summer 2013 working for the Support for Economic Analysis Development in Indonesia (SEADI) project in Jakarta.

Thanks for sharing this ftstanaic resource. I was pleased to see that Patient Voices covers a number of pediatric and adult diseases. These stories highlight families’ experiences and are a great illustration for both patients and health care workers.