On November 20, the President announced a new plan to protect nearly five million unauthorized immigrants, setting in motion the renewal of a fierce debate on immigration policy. While some have lauded the President on his efforts to move this issue to the forefront, the political right continues to attack President Obama’s Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) law for fueling the immigration crisis over the summer. Some on the Left cite his record as the president responsible for deporting the most undocumented immigrants in history. But Obama’s immigration record is far more complicated than either Republicans or Democrats suggest. As this debate heats up in Congress in the coming months, providing clarity and context is critical.

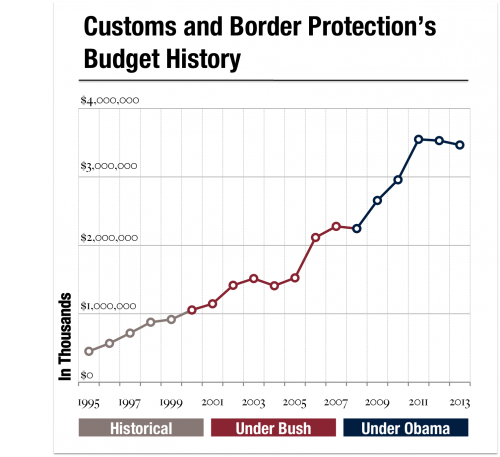

According to Homeland Security’s Budget-in-Brief, funding for immigration enforcement increased by about six percent under Obama. Customs and Border Protection’s “Fiscal Year Staffing Statistics” show a six percent increase in border staffing and a 30.5 percent increase in funding. While budget increases slowed with arrival of a Republican majority in the House in 2011, these numbers indicate anything but weakness in border control.

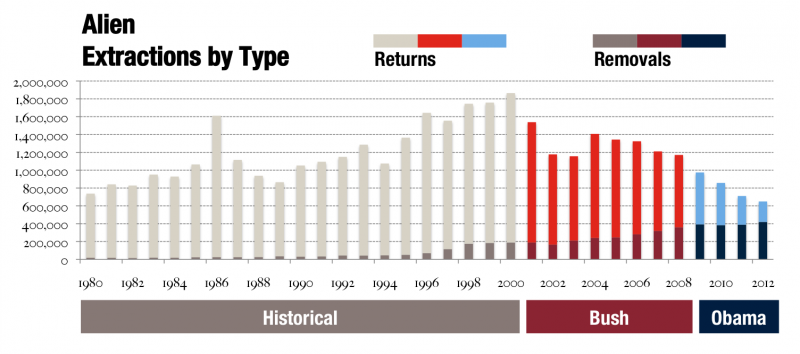

But funding increases have not been coupled with increases in extractions of undocumented immigrants. Extractions are differentiated into two categories: “removals” and “returns.” While “removals” (deportations) carry penalties for immigrants who reenter the country, “returns” refer to immigrants sent out of the United States without the long-term consequences of “removals.” Obama’s 45 percent increase over Bush’s yearly removals has been touted by Media Matters as evidence of Obama’s strong deportation record.

Yet, overall yearly extractions have declined under Obama. The statistic of total extractions has in itself caused a debate — the fact that removals carry strong penalties for repeat offenders might mean they are more valuable for border enforcement than returns. By providing legal penalties for those who repeatedly cross, removals help to deter future migrants from illegally immigrating.

The decline is best attributed to the falling rate of apprehensions. Obama cannot influence this without changing enforcement funding, and as shown previously, funding has increased during his presidency. The ratio between extractions and apprehensions under Obama is approximately the same as it was under Bush — 1.10:1. The United States is extracting more than it’s apprehending, in effect catching up on pre-2000 cases when the ratio was below one.

Thirty years of data on apprehensions and border staffing show a strong negative correlation between staffing and subsequent apprehensions. The small size of residuals from 2009-2012 when apprehensions are regressed with staffing and GDP growth implies that Obama deterred migrants in those years. However, correlation does not equal causation.

In spite of Senator Ted Cruz’s (R-TX) rants on amnesty, Deferred Action Against Childhood Arrivals merely called for “prosecutorial discretion” — reprioritizing deportation for criminals, instead of providing amnesty. And when immigrants talk of amnesty, they talk of “permisos,” not amnesty. ‘Permisos’ was introduced under Bush within the Trafficking Victims Reauthorization Act, allowing children to stay if a review showed that they had family in the U.S.

Neither of the aforementioned policies is responsible for the wave of recent immigration. Increased violence in El Salvador, Honduras, and Guatamala has caused children from these counties to flee to the United States, resulting in an influx of immigrants at the border. Though, the magnitude of this crisis is somewhat unclear, as Central American murder rates are notoriously hard to pin down— the UN reported over a 16 percent difference in its 2012 estimate for Guatemala than the estimate reported by the United States.

The first step forward in this debate is recognizing what we do not know. As the President said in his address, “We need more than politics as usual when it comes to immigration. We need reasoned, thoughtful, compassionate debate.” Only then can we begin to repair our broken system for immigration and accountability.