by Ryan Greenfield

Another month, another disappointing jobs report. The Bureau of Labor Statistics reported on Friday, October 8, 2010, that the U.S. lost another 95,000 jobs in September. What is most remarkable about this report is that private sector job growth was actually positive at 64,000 jobs (although this number is still not enough to keep up with the growth in the labor force). The private gains were more than offset by a huge decline of 159,000 public sector jobs including continuing layoffs from the end of the 2010 Census (77,000 jobs) but also cuts in state and local government (83,000 jobs).

States and localities operate almost entirely under balanced budget rules which prevent them, unlike the federal government, from running deficits. They face particular challenges in a recession because revenues from taxes on income, sales, property, and business profits fall, just as the need for services for the poor and unemployed (unemployment benefits, food stamps, Medicaid, etc.) grows. The $26 billion package signed by President Obama in August extended state aid for Medicaid and Education from the Recovery Act an additional six months past the December deadline. However, it is becoming clear that this money was completely insufficient to stem the loss of state and local public sector jobs.

According to the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, state governments face a projected deficit of $140 billion in Fiscal Year 2012 and $600 billion over the next 4 years. This will lead to an astounding number of job cuts and tax increases at the state level, act as a massive anti-stimulus and exacerbate the poor economy.

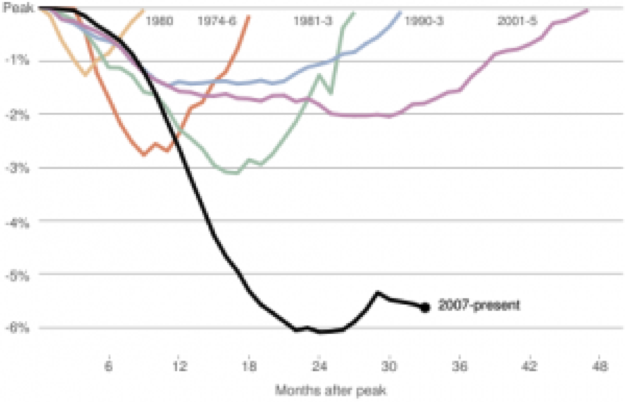

State and local austerity measures would not be as devastating if the economy were growing fast enough to bring substantial private sector job growth. But at the “America’s Fiscal Choices” conference on October 5, hosted by the several public policy think tanks in Washington DC, the panelists were close to unanimous that the prospects for substantially reducing unemployment were not good in the near future, and predicted that the U.S. probably will not return to anything resembling full employment (around 5.5% unemployment) for a decade or more. New York Times Columnist Paul Krugman referenced research about the aftermath of financial crises showing that unemployment and slow growth are particularly intractable compared to recessions not caused by financial crises. Krugman also predicted that without more fiscal stimulus, we may end up looking favorably on Japan’s “lost decade” in the 1990s of slow growth and deflation.

We also face large risks by cutting government spending prematurely. The Recovery Act spending is about to completely phase out at the end of December. In addition, the president’s debt commission is likely to issue its report to Congress after the elections in November recommending both tax increases and spending cuts. The end of the stimulus and implementation of additional fiscal austerity measures, while the economy remains weak, raises the possibility of a double-dip recession or deflation which, to say the least, would be actually detrimental to efforts to reduce the deficit.

The need for another round of stimulus spending is clear, although it is unlikely Congress will act. The current Democrat-dominated Congress was unable to reach consensus this summer to extend unemployment benefits to the long-term unemployed and restore Medicare payment cuts to physicians for weeks after both expired. The chance that the next Congress, with likely many more Republicans, will pass additional significant stimulus measures is remote. But getting more people working and paying taxes is the key to reducing the deficit. With monetary policy tapped out at near 0% interest rates, we simply cannot cut our way to economic growth nor a balanced budget.

Interest rates on 10-year government bonds (the interest rate at which the U.S. government can borrow money) are incredibly low, currently below 2.5%. With the economy likely to stay depressed for a long time, interest rates are unlikely to increase substantially. While there is often a worry that government borrowing will crowd out private investment, lack of demand in the economy is discouraging the private sector from utilizing loanable funds to expand. There is no better time for the federal government to borrow to upgrade our crumbling infrastructure, disburse aid to prevent states and localities from laying off workers and degrading vital public services, and investing in education and renewable energy, all of which will get people back to work while yielding long-term returns for American economic competitiveness.

http://washingtondcjcc.org/center-for-arts/literary/jewish-literary-festival/

Established in 1995, the Georgetown Public Policy Review is the McCourt School of Public Policy’s nonpartisan, graduate student-run publication. Our mission is to provide an outlet for innovative new thinkers and established policymakers to offer perspectives on the politics and policies that shape our nation and our world.