Introduction

Internal displacement refers to involuntary migration within a state’s borders. The UN’s Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement define an Internally Displaced Person (IDP) as an individual or group of individuals “who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes … to avoid the effects of armed conflict, generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized border” (UNHCR 1998). Approximately 71 million people worldwide qualify as internally displaced, including those affected by the Russia-Ukraine War, violence in the Democratic Republic of Congo and natural disasters in Pakistan (OHCHR 2023).

Internal displacement also occurs in non-crisis contexts. Despite its relative political stability, Colombia is the only country in the western hemisphere with over one million recorded displacement victims as of 2022 (IDMC 2023). Despite the magnitude of internal displacement in Colombia, there is a lack of empirical literature on this phenomenon. This paper seeks to synthesize the defining elements of internal displacement in Colombia, identify existing literature that analyzes this issue at the local level and outline potential areas for future research.

A Brief History

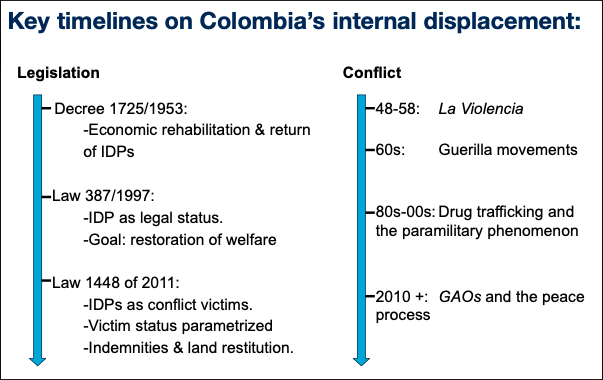

To understand internal displacement in Colombia, it is fundamental to review the country’s long history of conflict. While a detailed historiographical review is outside the scope of this paper, figure 1 attempts to synthesize the timeline of Colombia’s conflict alongside landmark legislative changes that constitute the foundation of the country’s institutional response to displacement.

Colombia’s history of armed conflict is intrinsically linked to forced displacement, and policy responses to forced displacement have evolved in tandem with the country’s history of violence. Law 1448 of 2011 (MinEducación 2023) is the most recent legislative development to address internal displacement. It formally recognizes IDPs as victims of the armed conflict and approaches the issue of displacement from a transitional justice perspective. Transitional justice refers to a country’s response to systematic or widespread human rights violations, with a focus on victim’s recognition and promotion of peace, reconciliation and democracy (ICTJ, 2023). In this sense, Law 1448 of 2011 legally recognizes forced displacement as an element of the Colombian armed conflict and sets the legal foundation for the recognition and reparation of displacement victims. The law also establishes a need-based criteria for IDP status eligibility, so that if an individual achieves stability, they are no longer considered an IDP.

This criteria builds on previous legislation and establishes that a person has achieved stabilization when their rights to identification, health, education, food security, housing, income generation, psychosocial attention and family reunification are fulfilled. The Unit for the Integral Reparation of Victims (UV) lays out the specific fulfillment thresholds for each item listed above and uses the Social and Economic Reestablishment Global Index (IRSE) to determine if a person has successfully overcome their vulnerable condition (UV 2021). Alternatively, displacement victims can choose to renounce their status (Ibáñez et al 2022, 604). The law also defines conditional financial indemnities of up to $10,000 USD per victim and restitution of abandoned land (Ibáñez et al 2022, 605) as reparations for victims.

Characterizing Internal Displacement in Colombia

|

Key characteristics: Internal displacement in Colombia. |

Colombia has one of the largest populations of conflict affected IDPs in the world and is the only nation in the western hemisphere with a large IDP population. |

|

Displacement in the country is unidirectional, with victims moving from rural to urban environments (Stirk 2013, 5) and rarely returning to their places of origin. |

|

|

Displacement is deeply intertwined with the country’s cycles of violence and rarely occurs as an isolated incident. Instead, it is linked to conflict dynamics between violent actors striving for territorial control (Ibañez & Moya 2007, 33). |

|

|

Territorial control is necessary as groups seek to profit from consolidated land ownership as well as illegal economies like coca and illegal mining. |

|

Key characteristics: displacement victims |

IDPs are often low-income small-scale landholders. Vulnerable populations such as women, children and ethnic minorities (indigenous or Afro-Colombian communities) are often overrepresented among IDPs. |

|

IDPs are not targeted by violent actors on the basis of a cohesive identity. Instead, they are targeted as a function of the territories they live in. |

|

|

Once displaced, IDPs face significant economic, physical, and psychological hardship, with the latter being the subject of a growing body of literature (Porter & Haslam 2005). |

|

|

Displacement victims only lose their IDP status if they pass away, renounce to it voluntarily, or if a designated government body establishes that the legally defined well-being threshold has been met. |

These characteristics have remained fairly constant despite Colombia’s history of forced displacement. Moreover, internal displacement in Colombia lacks international visibility, and there are few actors from the development ecosystem engaging in programs that specifically target IDPs (Shultz et al 2014, 23). Unlike most humanitarian interventions in developing countries, internal displacement in Colombia is largely addressed through the government’s existing institutional and policy framework, with international donors operating within the confines of established programs and having a comparatively minor role relative to the government (Ham et al 2022).

The Relationship Between Displacement and Poverty

Existing research on Colombia’s IDPs focuses on the relationships between the experience of displacement and poverty/well-being outcomes. Research has found that individuals’ income and consumption fall sharply after experiencing displacement, and they experience higher poverty rates compared to the non-displaced poor. Ibáñez et al (2022, 608) point out that while consumption shocks can be mitigated by government assistance, income and consumption levels among IDPs do not return to pre-displacement levels after a 12-month period. The effects of displacement are often studied using an asset loss model, meaning that displacement causes multidimensional loss of assets which hinders IDPs’ productive capacities and traps them in chronic poverty (Ibáñez et al 2022, 609). Some of the dimensions of asset loss explored through this model include physical assets (loss of land or other physical productive assets), human capital (skills not being transferable to job markets in host communities), and social capital (disruption of community networks that enable risk sharing).

Psychological capital is a recent addition to this body of literature, which describes how the psychological effects of displacement can trap victims in poverty. Empirical evidence indicates that experiencing displacement leads to an increased risk of anxiety and depression among IDPs relative to the general population (Moya 2018, 15). Research also indicates that exposure to displacement distorts cognition (Bogliacino et al 2017), increases risk aversion (Moya 2018) and leads to overly pessimistic perceptions about the ability to recover and move out of poverty (Moya & Carter 2019).

Researchers have also explored the intergenerational effects of displacement, with a particular focus on education. Some evidence indicates that school enrollment and completion among children born in displaced households can be higher than children born before the displacement event (Monroy 2018). However, educational outcomes are lower for children of displaced households when compared to those of other urban poor who are not IDPs (Ibañez & Moya 2007, 52). Moreover, exposure to displacement also hinders early childhood development, compounding the generational effects of displacement. Children who experience displacement itself are more likely to face chronic malnutrition and have lower size-for-age scores than children in the same families who did not experience the shock of displacement during early childhood (Becerra 2014).

There is evidence that the negative effects associated with displacement are smaller if the displacement was preventative instead of reactive (Velez 2008). In other words, the welfare impact to a household that decides to leave their residence based on a perceived threat, or in anticipation of escalating violence, is lower than that of a household that leaves in reaction to a violent event that has already taken place. The distinction between reactive and preventative displacement is broadly used among researchers focusing on Colombian IDPs, although administrative data collected by relevant government agencies rarely makes this distinction (UV 2015).

Evaluations of existing policies reveal that simply including IDPs in existing anti-poverty programs does not lead to improved outcomes among IDPs. An evaluation of the Familias en Acción program, one of Colombia’s landmark conditional cash transfer initiatives, concludes that while the program has a positive effect on children’s education, health, and nutrition, it has little impact on malnutrition risk, which disproportionately affects displaced households. Furthermore, the program is not successful at improving household well-being, household income, economic independence, or self-sufficiency (CNC 2008), meaning that traditional anti-poverty initiatives are not effective in helping IDPs to overcome their status.

Preliminary evaluations of IDP-specific programs have reached similar conclusions, with researchers finding that the positive effects dissipate shortly after the programs end (Helo Sarmiento 2009). That being said, there is evidence of the effectiveness of policies like financial indemnities and land restitution for improving the economic and social conditions of victims (Guarin et al 2023) as well as supporting their process of healing and trust (Bogliacino et al 2022). There is a need for programs that go beyond immediate-need support, focusing on addressing long term needs and promoting economic agency and autonomy (Ham et al 2022). A possible path to achieve long-term success is to incorporate psychological support into intervention design on top of standard income-generation programs. Some research indicates that simple job-oriented soft-skill development may be ineffective (Ibáñez et al 2022, 616), whereas programs that incorporate more advanced psychological interventions, such as mental imagery (Ashraf et al 2021) can have significant positive effects.

Conclusion and Future Research

Displacement in Colombia is an ongoing issue that has been relatively understudied and lacks broad international recognition. Academics who study the phenomenon have relied on the asset loss model as a framework to articulate their research. This model has allowed for novel additions to the literature, such as psychological asset loss and generational effects, which have broadened the conversation on the long-term effects of displacement among victims. In addition, displacement victims in Colombia rarely have access to interventions that target them directly, but instead receive preferential access to existing anti-poverty schemes. Regardless, there is a clear need for further empirical evaluation work on both types of interventions. Lastly, there is a clear gap in the literature on the effect of displacement on host communities in Colombia, which is a promising avenue for future research.