Last year was one of the worst years in modern American (and global) history. The COVID-19 pandemic has now killed over 500,000 Americans and has severely damaged the nation’s economy. Millions are still out of work, many cannot afford mortgage and rent payments, and tens of thousands of local businesses have permanently shut down. Congress stepped in to provide relief for small businesses, the unemployed, renters, and the general public, though it is still debatable if they have done enough. However, though the spending was necessary, what is not debatable is the contribution this made to the $3.3 trillion federal budget deficit during the 2020 fiscal year, the largest in history.

Most economists and experts from across the political spectrum agreed that the federal stimulus given throughout 2020 was necessary to prevent economic collapse. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell, who has warned Congress of the potential consequences of fiscal irresponsibility in the past, frequently stated that Congress should spend more to keep the economy afloat. Even Doug Elmendorf, former Director of the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), argued that “more than $1 trillion of additional fiscal support is warranted.” The argument being made by both of these fiscal hawks, along with most fiscal doves, is that if Congress does not provide support, the economy may collapse further—necessitating more spending to provide future recovery.

According to common fiscal theory, the federal government should balance the budget during times of economic growth and peace so that policymakers have more tools to provide relief during times of hardship, like amidst a pandemic. Though ubiquitously endorsed by most, the relief packages are the primary contributor to the year’s historic deficit. In 2020, the overall national debt exploded from 79% of the nation’s GDP to approximately 100%, a debt-to-GDP ratio not seen since the end of World War II. Shortly after the end of this war in 1945, policymakers in Washington reduced the debt ratio through a combination of increased revenues and decreased expenditures. The prospects of lawmakers doing the same look bleak; over the last few decades, Democratic policymakers have generally refused to cut spending and Republican lawmakers have been averse to raising taxes.

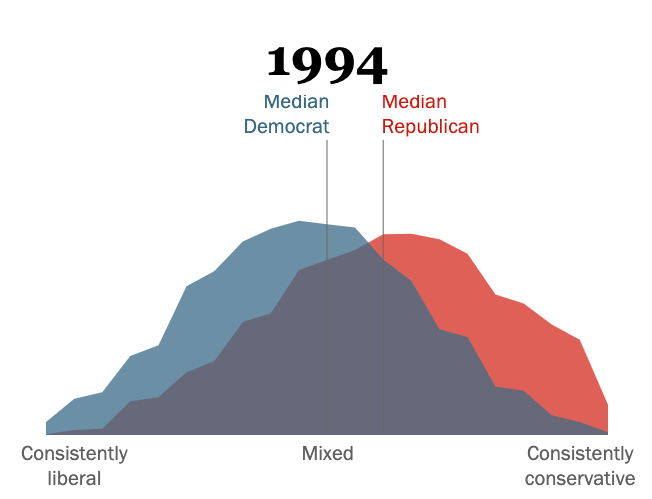

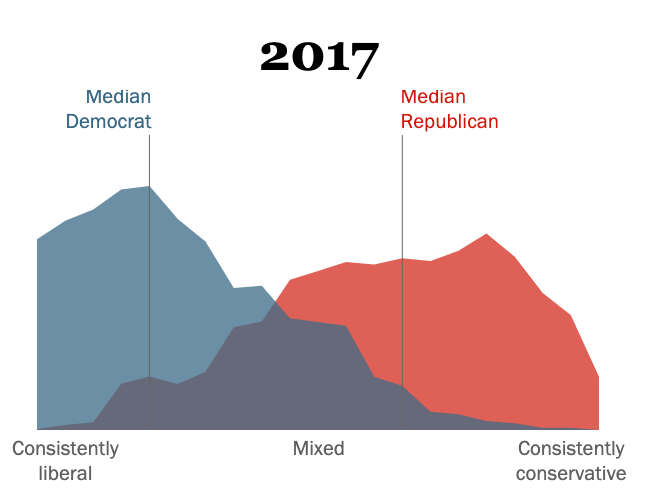

Growing national polarization in recent decades has factored in preventing Democrats and Republicans from compromising on this issue. Partly due to sorting, Congressional Democrats have little incentive to cut spending and Republicans have little incentive to raise taxes, fearing primary challenges from more radical candidates. This conundrum, coupled with the absence of a political constituency calling for debt reduction and deficit-neutral spending, deters lawmakers from fiscal responsibility. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget is the main advocacy organization that informs lawmakers and the public on the consequences of the federal debt, but without strong grassroots efforts, their ability to make fiscal responsibility a priority in Congress is limited.

|

|

Data from Pew Research Center.

Though this issue has low salience in Congress and in the Executive Branch, the fiscal health of the federal government is nonetheless critical to the future welfare of the country. The ramifications of uncontrolled debt could adversely impact the future state of the economy, hamstring the government’s capacity to address future economic crises and even threaten national security. Even before the pandemic, many economists warned that the federal debt was already on an unsustainable path.

When the federal government needs to borrow money, they issue debt instruments—mainly in the form of Treasury Bonds—which foreign governments, central banks like the Federal Reserve, and institutional and retail investors purchase. American bonds are seen as a safe investment because the U.S. has never defaulted on a debt payment in the history of the modern financial system, meaning investors consistently make back their investment plus interest once the bond matures.

However, just because default has yet to happen does not preclude such risk in the future. The CBO projects the national debt-to-GDP ratio will skyrocket if federal fiscal policy maintains the current course. While relying on future Congresses to simply not spend as much and raise revenues through taxation may seem like a viable solution, the government’s options may be inhibited by piling interest payments on current loans (a rapidly-growing part of the deficit), particularly once the current, controversially-low interest rates increase. These growing interest payments are projected to be the most rapidly increasing contributor to federal deficits in the future.

While discretionary spending on items like healthcare and national defense plays a role in the projected increase, mandatory spending on programs like Social Security and Medicare is the primary contributor. As the population ages, these programs are continuing on the path towards insolvency. The more money that is required to be spent on these necessary programs, the more interest is accumulated when these programs are financed through debt. By 2035, interest payments will account for half of the federal deficit—the highest ratio in modern history, likely crowding out much-needed investments in sustainable infrastructure, healthcare, welfare, and more. This crushing interest could also hinder the government’s ability to finance future responses to recessions, pandemics, and national security threats.

Critics of those who sound the alarm on the national debt frequently suggest the fiscal and monetary tools of the government and the Federal Reserve will render deficit concerns moot. Proponents of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) argue that government deficits should not matter for countries with their own central banks as these nations can greatly influence their own money supply and can borrow money from domestic investors. While it is true that the federal government does not need to necessarily balance the annual budget every year, the extent to which these theorists believe that the federal government can freely spend and keep increasing the money supply is irresponsible. As the Cato Institute notes, this theory “does not credibly reveal more scope for deficit spending without inflation.”

The U.S. dollar is, like all other valuables, subject to the laws of supply and demand. If supply far outpaces demand, then the item loses value. Though the Federal Reserve has tools to control inflation, irresponsible spending would limit the effectiveness of those tools. By the nature of MMT’s fiscal expansionary theory, increasing deficits and the supply of money to fund programs carries the risk of inflation. The rise of digital currencies could also challenge the U.S. dollar’s position as a premier reserve currency, which constitutes potential exogenous demand shocks against the U.S. dollar.

If inflation were to drastically increase, the U.S. could struggle to pay back its debts, especially with a federal debt-to-GDP ratio approximating 100% and with CBO projections that by 2050 that ratio will nearly double to a stunning 200%, if policies are not drastically changed. The existing deficit concerns factored into Standard & Poor and Fitch downgrading the U.S. credit rating over the last 9 years. These trends could put upward pressure on interest rates and make it more difficult for the federal government to manage interest payments, risking the prospect of default, which would create a global economic calamity. This potential disaster would result from creditors losing confidence in U.S. bonds, massive inflation, skyrocketing interest rates, and a breakdown of the global financial system which greatly relies on the strength and stability of the U.S.

Unfortunately, though the issue is pressing, neither party takes the issue seriously. Though an increase in spending was needed to boost economic recovery after the 2008 economic crisis, the Obama Administration never made serious efforts to balance the budget, as debt-to-GDP increased from 52% in 2009 to 76% in 2016. Former President Trump, a candidate who promised to eliminate the debt, saw his Administration and Republican Congress increase the annual deficit to around $1 trillion before COVID-19, in large part due to the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. Though the Republican Party has claimed to be the party of fiscal responsibility, this has generally not been shown in practice over the past two decades.

While Republicans are often insincere about making fiscal responsibility a priority, some of the progressive agendas percolating in the Democratic sphere would greatly exacerbate the current debt crisis. Current “Medicare-for-All” proposals would add roughly $34 trillion to the federal debt over 10 years, a figure that would compare to having the U.S. fund COVID-19 packages every year for this time period. Though “Green New Deal” proposals often vary in scope, most of the policies would also add significantly to the federal debt. This is not to say that the federal government should not find solutions for rising healthcare costs and the existential threat of climate change, but there are other alternatives that would help address these pressing issues. Besides, these progressive plans would have to be funded through massive tax increases that would certainly stymie economic growth and most likely not be exclusive to the higher income earners.

The unwillingness for both Democrats and Republicans to take initiative puts the federal budget in a perilous position. The apathy of previous administrations and Congresses left the U.S. unprepared to bear the cost in times of need without aggravating the fiscal situation. If history is any indication, the Biden Administration and 117th Congress are unlikely to meaningfully act, even after the health and economic effects of the pandemic are stabilized. Top economists from the Treasury Department, Federal Reserve, and CBO have raised red flags about our unsustainable fiscal path. Unfortunately, we may not realize this until it is too late for us or our posterity.

Photo by Daniel Berek.

3 comments

[…] I am hearing about this and witnessing it as Sharon and I visit our local restaurants, STAFF SHORTAGES! Love on these folks and tip well! Show them the love of JESUS! I am told by staffs of restaurants that they cannot get enough people to work! All our kids are working long hours from nursing to working at Target. Sharon and I were taught and our kids were taught to work! WORK FOR A LIVING! Time to get America back to work and off the government payroll! We got to start moving as a Country!!! THE FEDERAL DEFICIT STILL MATTERS, NOW ARGUABLY MORE THAN EVER […]

[…] I am hearing about this and witnessing it as Sharon and I visit our local restaurants, STAFF SHORTAGES! Love on these folks and tip well! Show them the love of JESUS! I am told by staffs of restaurants that they cannot get enough people to work! All our kids are working long hours from nursing to working at Target. Sharon and I were taught and our kids were taught to work! WORK FOR A LIVING! Time to get America back to work and off the government payroll! We got to start moving as a Country!!! THE FEDERAL DEFICIT STILL MATTERS, NOW ARGUABLY MORE THAN EVER […]

.

Quoting Cato is not an argument.

Digital currencies are a ridiculous non threat to USD reserve status.

You miss the biggest threat: anemic gdp growth rates that allow China to become twice our economic size in a third of a century.

.

Comments are closed.