Historical associations of Blackness with risk and Whiteness with stability along with broader forms of implicit biases continue to reinforce racial disparities in credit and housing, impacting rates of homeownership among Americans.

Homeownership: the core of the American dream, a proven tool for upward mobility and deeply entrenched in the national psyche. Yet, almost equally American, the history of homeownership mirrors hundreds of years of inequity, racism, and repression—a history that reverberates throughout our society today. Until the 1970s, the U.S. legally upheld a range of overtly racist policies and practices that prevented people of color from owning a home while subsidizing homeownership for White Americans. Many of these explicitly racist practices have since been struck down, yet rates of homeownership remain vastly different across racial and socioeconomic groups in the United States. In fact, the gap in homeownership rates (as of 2017) is wider than it was when race-based discrimination against homebuyers was legal.

At the heart of this story is the role of implicit bias. The evidence partially attributes implicit bias in housing and credit, specifically in the assessment of risk, to the racial disparities in homeownership rates today.

Role of Implicit Bias

Since the prohibition of race-based discrimination in housing, overt racism accounts for a smaller percentage of the gap in homeownership rates. While explicitly racist prejudice still occurs in the housing market, the dwindling prevalence forces us to look elsewhere for explanations.

Implicit bias is difficult to isolate as a contributing factor to housing discrimination. Implicit biases are “attitudes or stereotypes that affect our understanding, actions, and decisions in an unconscious manner” and can persist even when an individual has made a personal commitment to equality and inclusion. Paired testing is a helpful and widely-used tool employed to investigate the role of implicit bias in the housing market. For example, the latest Housing Discrimination Study utilized a paired test to compare two home-seekers, identical in every way except for race (one individual was White, the other non-White). Participants visited real estate agencies to inquire about specific housing units and their experiences were measured. The study revealed that White homebuyers are favored over Black homebuyers in 17% of tests; they were more likely to be shown units in White neighborhoods, more likely to be invited to inspect homes and received more information and assistance with financing. The impacts of these disparities in access go well beyond the face value; the biases contribute to the increased cost of homeownership among African American and other minority home-seekers which compounded over time contribute in a significant way to the homeownership gap.

Role of Risk Assessment

So, what is it exactly about race that drives implicit perceptions and decision-making in housing and credit?

One suggested factor is the historical association of Blackness with risk and Whiteness with stability— a more specific brand of implicit bias. This stigma has historical roots in the discriminatory lending practices of the Federal Housing Administration and Homeowners Loan Corporation. Prior to the passage of Titles VIII and IX of the Civil Rights Act of 1968 (known as the Fair Housing Act), banks and federal agencies openly associated race and risk resulting in explicitly discriminatory practices (i.e., redlining). In the post-Fair Housing Act era, the association of Blackness and risk endures. One possible reason this trend has persisted is through “negative information effects”— i.e., the absence of lending activity leads to “an underestimation of the value of homes.” Negative information effects create a vicious cycle; low lending activity leads to lower appraisals, which further depresses lending activity. This cycle can also spur higher lending costs for borrowers, which also depresses lending.

Risk assessment is an inherent part of the housing and credit markets, making it fertile ground for implicit bias (specifically racialized risk assessment) to have a significant impact on the demographic and geographic makeup of our neighborhoods.

Effects of Implicit Bias and Racialized Risk Assessment in Housing and Credit

We see racialized risk assessment and other kinds of implicit bias in many aspects of the housing and credit markets, steadily increasing costs of homeownership for minority home-seekers.

Credit and Lending

Differences in the terms, cost and availability of loans between White and non-White borrowers are stark. Black and Hispanic people face higher rejection rates and less favorable terms in securing mortgages than do whites with similar credit characteristics. In fact, African American borrowers pay on average over half a percent higher interest rates on home mortgages as compared to their White counterparts of the same income level, age and date of purchase.

Non-White borrowers also face hurdles in getting a mortgage at all. Having poor credit or abnormalities in credit history are more often overlooked for White applicants compared to minority applicants; Black and Hispanic applicants are 82% more likely to be rejected for a home loan than White applicants with otherwise similar characteristics.

Access to Housing

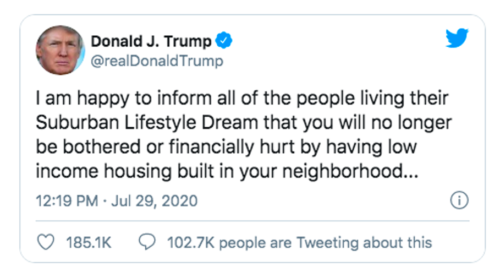

NIMBYism, the anti-development “not in my backyard” mindset, is another form of racialized risk assessment contributing to the homeownership gap. NIMBYism typically refers to opposition to new development in the name of retaining neighborhood character or fear of decreasing property values. With so many cities in the nation facing severe housing shortages, construction of new units (both market-rate and affordable) are necessary to combat the growing crisis. Yet, NIMBY attitudes have effectively slowed the push for additional development. This mindset is accurately captured in a tweet from President Trump from July 2020:

NIMBYism is essentially a modern take on the same economic argument used to justify exclusion when racial segregation was legal— fear of decreasing property values because of new development and “undesirable” residents coming into the neighborhood. This determination is not explicitly linked with race. Instead, that fear is focused on the impact of low-income individuals moving into a neighborhood. However, race plays a role in this attitude as well. There is a general perception of majority-minority or diverse neighborhoods as less affluent, less safe and less desirable compared to white neighborhoods.

Yet, fears about the impact of affordable housing or public housing developments depressing property values are empirically unfounded. Low-income housing projects have no significant effect on home values.

Policy Implications

Homeownership is the primary tool for building wealth in this country. Homes tend to be a family’s largest asset and a key way of passing wealth from generation to generation. Owning a home also protects from exogenous shocks, like a recession, gentrification, or the economic fallout of a pandemic. Given that the “net worth of a typical white family is nearly ten times greater than that of a Black family” and that the gap between Black and White homeowners is the widest it has been since the signing of the Fair Housing Act, we must look at the growing rift in homeownership rates as both a cause of economic inequality and area for potential impact.

However, addressing implicit bias is inherently complicated. Defined by the unconscious impact on outcomes, targeting implicit biases must reflect an understanding of how they manifest in housing and credit. For example, gaining a deeper understanding of how risk assessment impacts access to credit provides a foundation to rethink how we evaluate credit in this country. Some have suggested that changing how we gauge good vs. bad credit in a fairer and more modern way can help alleviate the disparities caused by implicit biases. Considering the underlying implications of NIMBYism can also help guide local officials when facing opposition to new developments, and by creating more structured processes in the real estate market it is possible to reduce human error and the potential for biased action.

Doing away with explicitly discriminatory policies in housing and credit is not enough; addressing implicit bias is the next frontier in the fight for racial equity and equal access to opportunity.

Photo by George Becker from Pexels.

Rachel brings a blend of experience in investigative journalism and land use/development policy to the GPPR team. Her policy interests are focused on the intersection of market-based incentives and public policy, particularly as it relates to housing and urban development. An Oakland CA native, Rachel graduated from the University of California, Los Angeles in 2018 and has spent the last few years working at an LA-based boutique public policy and communications firm focused on regional issues.