The United States is one of two countries that does not provide any sort of national paid leave. Currently, only 19% of U.S. workers have access to formal paid family leave provided by their employers, while around 60 percent of workers have access to 12 weeks of unpaid leave through the Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA). Only companies with 50 or more employees are required to provide FMLA, leaving employees of smaller organizations without coverage unless voluntarily provided by their employer.

Access to paid family leave is likely to increase due to the passage of this year’s National Defense Authorization Act, which includes a provision that gives more than two million federal government employees access to 12 weeks of paid time off for the birth or adoption of a new child. Several states and the District of Columbia have also passed their own forms of paid leave legislation since 2004. Growing bipartisan popularity among voters has resulted in both Republican and Democratic representatives introducing legislation for a national paid family leave plan, although their approaches to paying for the program, levels of wage replacement, and amount of time off vary.

Paid family leave, and especially leave that lasts at least 12 weeks, has positive effects on both children and mothers’ physical and mental health. However, research on the impact of family leave on encouraging women to remain in the workforce is mixed, with implications for gender equity. On one hand, the 1997-2009 National Longitudinal Survey of Youth finds that women who report taking time off are more likely to be working nine to 12 months after giving birth. On the other hand, research on California’s 2004 Paid Family Leave Act shows that women who used paid family leave during the law’s first year of implementation actually saw a decrease in both the amount of time they worked and money earned one decade later.

This research points to an interesting potential conclusion. Incentives for working women to dedicate time to family may support their short-term productivity but may also contribute to pervasive gender differences in employment outcomes. Access to paid family leave can increase children’s wellbeing and family financial stability, but a family leave policy that excludes fathers likely harms both working women and working men. Designing a federal paid leave policy in a way that encourages the full participation of fathers, who frequently only take a few days off, is one way to increase positive outcomes for parents, children, and the economy.

Benefits of paternity leave

Increased early childhood paternal involvement is correlated with long-term benefits for both the child and father. Researchers found two weeks of leave-taking for father-child bonding was associated with a . This leads to an increased amount of satisfaction fathers feel when engaging with their children. Forming this type of attachment also leads to fewer childhood behavioral problems and increased social, emotional, and cognitive development.

Interestingly, paternity leave is also associated with better economic and health outcomes for mothers. In Sweden, a 2010 Institute for Labour Market Policy Evaluation report demonstrates that each additional month a father takes leave increases a mother’s earnings by 6.7%, which has a greater impact on the mother’s earnings than her own leave. In addition, mothers in heterosexual relationships whose partners were able to take time off are found to have higher levels of postpartum mental and physical health.

Countries that encourage men to take paternity leave tend to have higher rates of gender equality at home and in the workplace, which contributes to healthier and more stable parental relationships. Fathers who take leave tend to participate in more of the unpaid household work, typically done by women, than those who do not. This allows women to spend less time on childcare and household chores and more time in paid work. More egalitarian parental relationships also result in increased parental stability and a decrease in divorce rates for years after taking leave. According to a 2019 report in the Journal of Social Policy, even a relatively short period of leave taken by fathers (one to two weeks) is associated with lower divorce rates, while a leave of four weeks has a more positive effect on relationship stability.

Explanation for low participation among fathers

While paid family leave has increased in popularity over the years, only 9% of fathers have access to paid leave in the United States. Through the FMLA, eligible fathers can take a maximum of 12 weeks of unpaid leave. However, according to a 2011 survey, most fathers take a fraction of this time off: 76% of fathers reported that they return to work within a week of birth, while 96% were back to work within two weeks.

Many fathers, particularly those who only have access to unpaid leave, are unable to take time off due to financial constraints. This likely explains why low-income and minority fathers are the less in both paid and unpaid leave due to fear of penalties from employers. This fear is understandable due to the consistent finding that women who take leave to care for a child, or even request more flexible work schedules, are likely to be paid less and hired for jobs at lower rates than their male peers with the same qualifications. One study estimates that men’s earnings drop by an average of 15.5% throughout their careers when they request more flexible work hours to care for family members, compared with 9.8% for women who do the same. Men who seek flexible work arrangements have also been given lower performance reviews and have a greater risk of being demoted or laid off.

Conclusion: Overcoming social and economic stigma through paid paternity leave

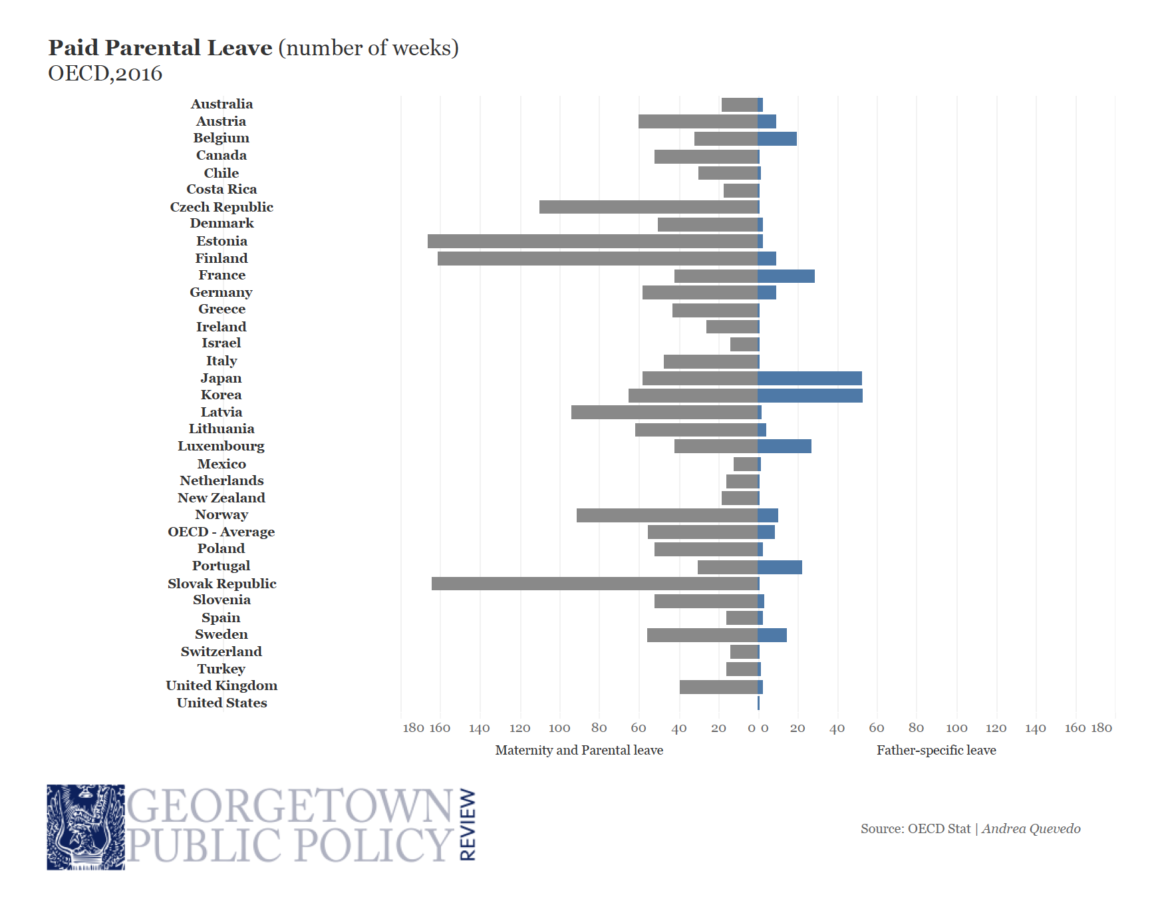

When designing a national paid family leave policy, the United States should look to European countries for ways to encourage fathers’ participation. have begun setting aside paid parental leave specifically for fathers, often known as “daddy quotas.” These policies give fathers and nonbiological mothers in same-sex couples several weeks of “use-it-or-lose-it” time off when welcoming a new child. Jurisdictions that implemented it found that dedicating a specific leave to these groups, and the ability to miss out on the benefit, made them significantly more likely to participate.

For example, almost immediately after Quebec implemented a five-week daddy quota in 2006, the take-up rate jumped dramatically, with over 80% of eligible fathers taking leave. This is compared to less than 20% of other Canadian fathers who participate in a shared leave program where the leave must be divided by couples. Norway saw similar results in the years following implementation of a paternal quota, with 70% of eligible fathers taking leave compared to 2.4% in the year prior to its creation.

Designing and implementing this policy in a way that allows families from all socioeconomic backgrounds to reap the benefits is crucial. Guaranteeing job protection and increasing the amount of wage replacement for fathers, particularly those with lower incomes who likely rely more heavily on regular paychecks, are also crucial. One way to do this is implementing a progressive paid leave structure, similar to Washington state, where low-wage workers can receive up to 90% of their regular wages. As a family’s income increases, its level of wage replacement decreases.

In addition to designing a comprehensive policy for both mothers and fathers, the United States must work to encourage men to participate in equal caregiving responsibilities and end the stigma against fathers who utilize the maximum amount of leave. This often depends on the work culture and how encouraging managers are of men taking leave. Seeing men in the workplace, especially senior professionals, take leave without facing professional and economic consequences encourages other men to do the same.

Wonderfully written and bringing attention to a very important topic that is not talked about enough!