What is the current party division of the U.S. Congress and state governments, and how does this impact legislation at both levels of government? A historical analysis of federal and state party compositions may offer insight.

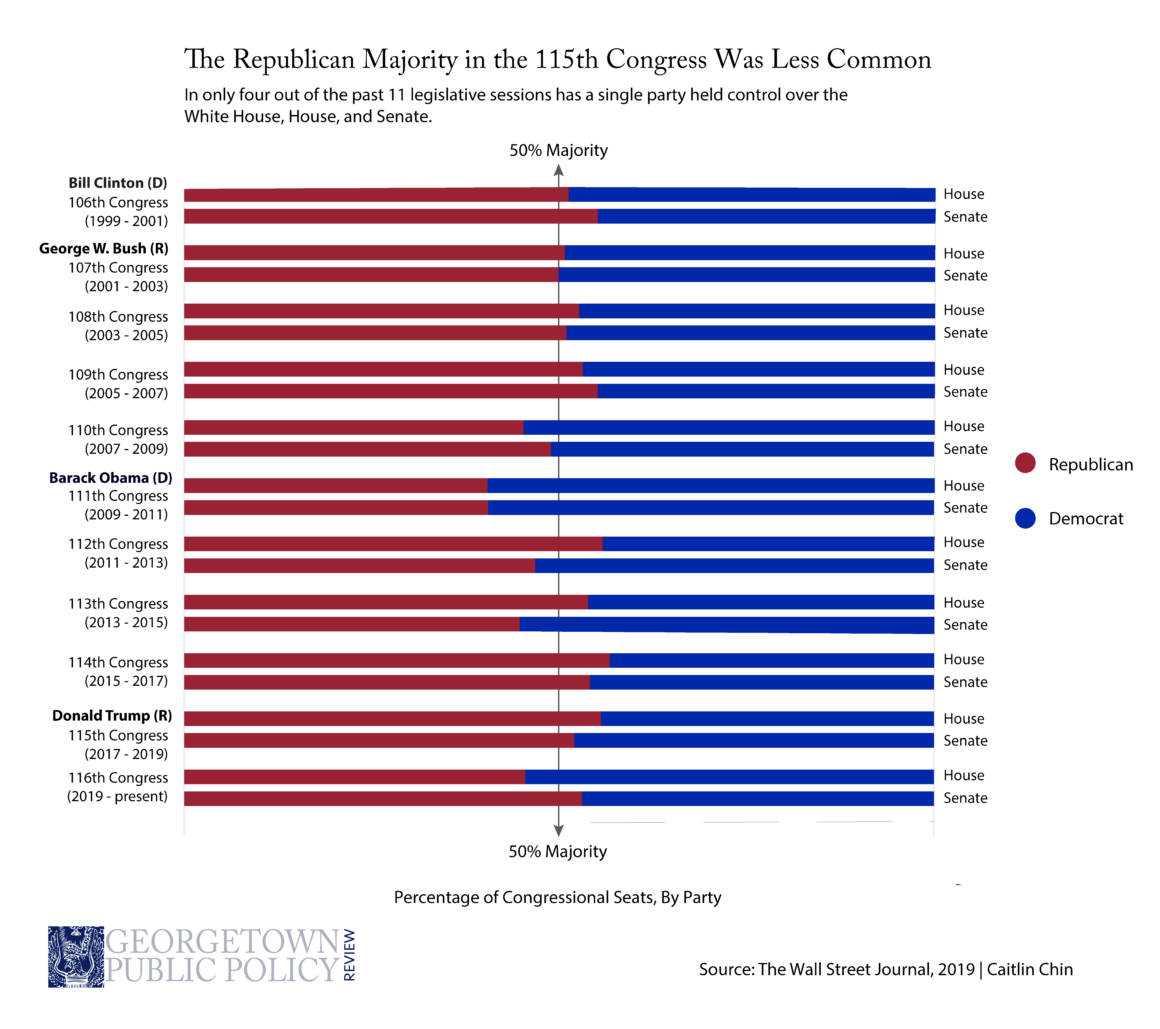

In the 2018 midterm elections, Democrats gained a majority in the House of Representatives, thus ending a two-year period of Republican control over the White House and both chambers of Congress. This shift in party control is historically unique—not because Democrats gained control over the House, but because they did not gain control over the Senate as well.

Split Congresses are rare. In fact, the House and Senate have only experienced split party control a few times in the past century: from 1931-33, 1981-89, 2011-15, and finally, from 2019 to the present. During all other legislative sessions, Democrats and Republicans have traded single-party majorities in both the House and Senate.

However, even a Congress controlled by a single party is not devoid of division. Bill passage rates are vulnerable not only to internal divisions within Congress, but also to ideological differences between Congress and the White House. Although it is unusual for two parties to concurrently split control over Congress, it is also uncommon for a single party to simultaneously control both Congress and the White House, as the Republicans had in the 115th Congress. In fact, opposite parties controlled the legislative and executive branches in 22 of the past 36 legislative sessions, including seven of the most recent 11 sessions.

How do state governments compare?

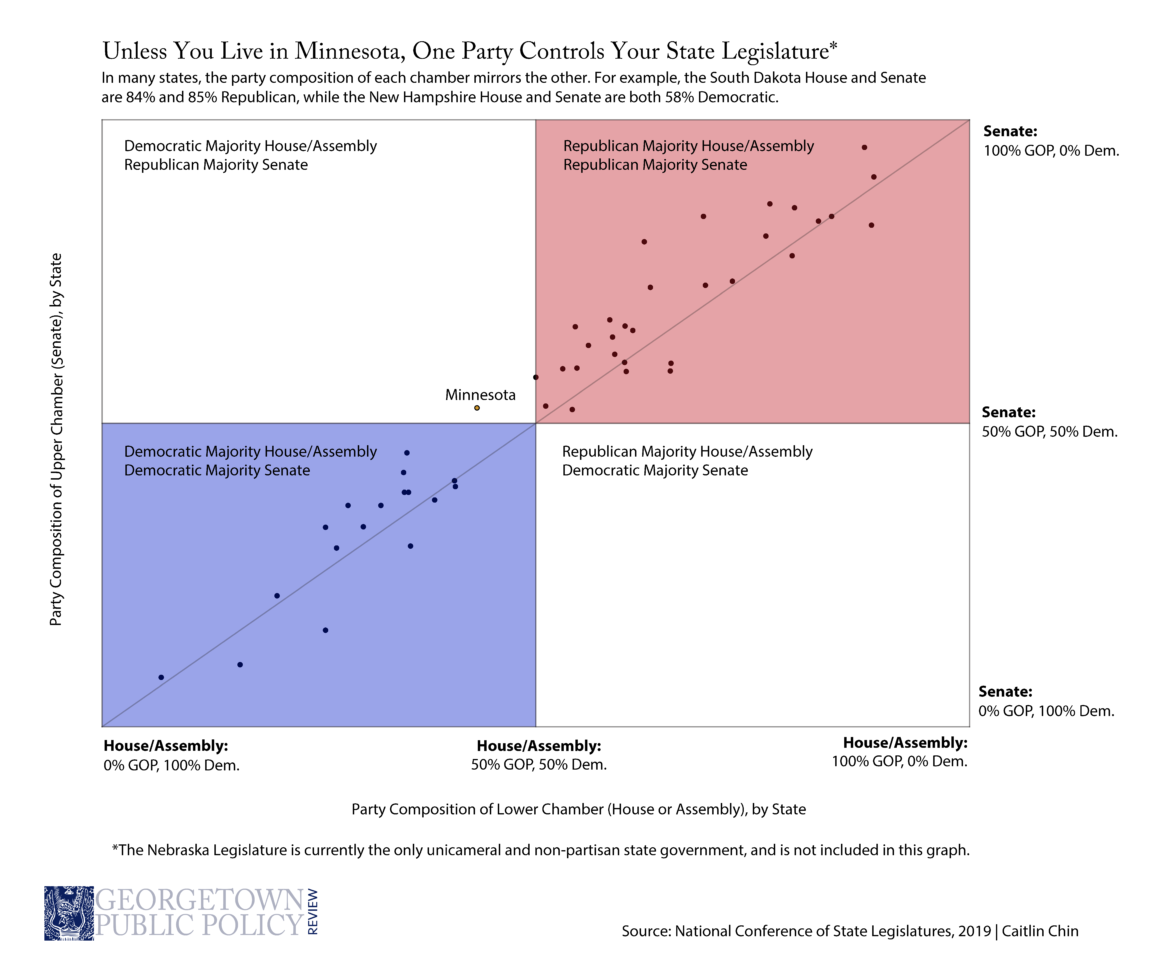

Like Congress, almost all state legislatures are bicameral (except the Nebraska Legislature, which is unicameral and non-partisan). Also like Congress, a single party often controls both chambers of state legislatures.

In fact, state legislatures are currently experiencing single-party control in every state but Minnesota. Minnesota is one of only a handful of states—which includes Colorado, Iowa, Kentucky, Maine, Minnesota, New Mexico, New York, and Washington—that have experienced a split legislature at least once over the past couple election cycles.

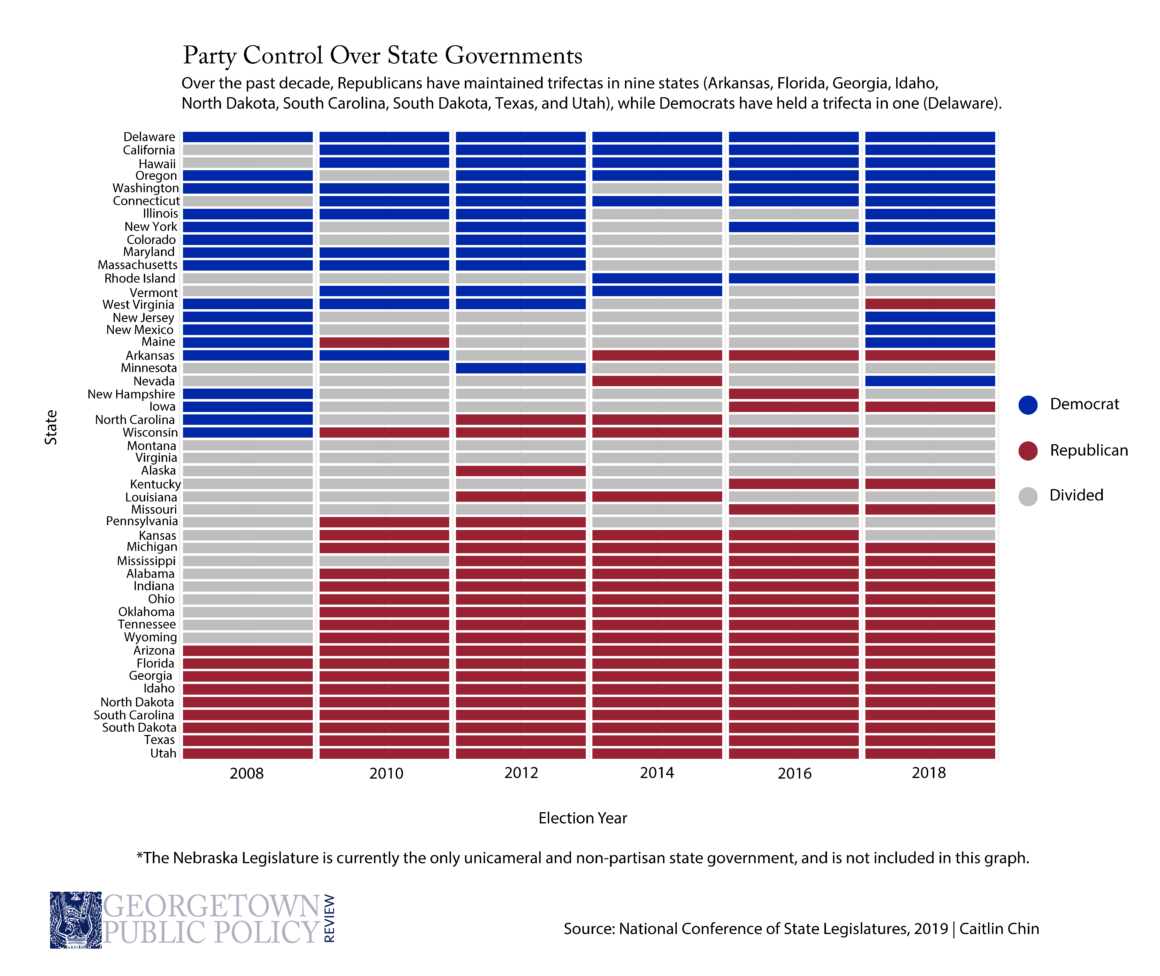

However, when it comes to single-party control over both the executive and legislative branches, states are more internally unified than the federal government is. In fact, 36 states currently experience single-party control over both legislative chambers and the governorship in what is known as a “trifecta,” or total state control. Over the past decade, the total number of trifectas nationwide has grown from 26 to 36, with the number of Republican trifectas increasing from nine to 22.

What are the public policy implications of federal and state party compositions? A preliminary examination of the data suggests that states are becoming more divided: trifectas are becoming more common, especially among Republican-majority states. Going further, federal and state party compositions could affect the passage of legislation and harmonization between laws.

Single-party controlled state governments are more likely to enact new laws.

At the federal level, there is a significant gap between total bills introduced and the number of bills signed into law. According to GovTrack, members of Congress have introduced over 9,000 bills and resolutions since January, but enacted just a fraction of that amount (68 bills) into law.

States also introduce far more bills than they ultimately sign into law, but nonetheless they enact legislation at far higher rates than Congress does, according to legislative data that CQ and Quorum compiled.

One possible explanation for this phenomena is party composition. Although legislation typically struggles to pass even single-party Congresses, bill passage rates have seen further downward pressure during split Congresses. For example, during the most recent period of divided legislature (from 2010 to 2014), the 112th and 113th Congresses passed fewer laws than in any other modern legislative session. States, however, are historically and statistically more likely to experience both trifecta-control and higher bill passage rates.

We can expect major ideological divergences in enacted state laws.

While single-party politics might help state governments avoid legislative gridlock, it could also result in significant differences in both the nature and frequency of laws in certain policy areas—including widely-varying abortion, gun control, and marijuana policies in different states.

As we can see from these three examples, partisanship can be reflected in the type of policies that governments choose to establish. Going forward, the party compositions of the House, Senate, White House, and state governments could have significant implications for public policy in the coming years. While the outcome of the 2020 elections is uncertain, if historical patterns continue, then single-party state control will become the new norm and federal polarization will prevail.

Caitlin Chin was a senior online editor for the Georgetown Public Policy Review and a M.P.P. candidate at the McCourt School. She holds a bachelor's degree in government and Spanish from the University of Maryland.