While foreign labor in Saudi Arabia has become more expensive due to a government levy, demand has nevertheless increased, leading economists to question whether or not it is a Veblen good. What does the data say, and what are the policy implications?

The expatriate dependent levy

Over a year and a half has passed since the Saudi government began imposing a fee of $26 per month on foreign dependents regardless of their age. The Ministry of Labor and Social Development introduced the levy fee to reduce the number of foreign workers in the labor market, who currently compose 83 to 84 percent of the private sector. The fee is applied on all foreign laborers, with some exceptions given to Syrian and Yemeni families. The Ministry of Labor and Social Development’s plan includes raising the fees annually until 2020, as part of Saudi Arabia’s National Transformation Plan, to approximately reach $106 per month, for each foreign dependent.

A look at data from the General Organization for Social Security tell us that the number of expat workers, particularly low-income and unskilled workers, has declined significantly in the past 12 months. However, it is unclear whether this change is attributable to businesses becoming more efficient in allocating their resources or whether it is caused by the new monthly fees. Some have claimed this year that foreigners are leaving the country, and at a fast pace ever since the introduction of the foreign dependent fee in July 2017. This has led some to support the conclusion that the ratio of foreign to Saudi nationals has declined, or at least stabilized, as a result of the fees. However, as I have pointed out before, this conclusion may only describe part of the trend – that the fee only impacts expat workers at the bottom of the earnings ladder – as recent Saudi census data suggests when compared to the overall expat population.

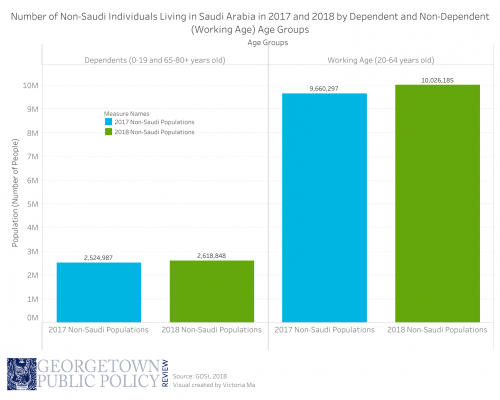

Researchers often conflate two separate, yet related, trends. For example, although the overall number of foreigners in the country may have declined due to a decrease in the number of foreign workers, this has not been the case in the past 12 months. In fact, according to the 2018 population census, between 2017 and 2018, Saudi Arabia’s total foreign worker population, including both outflows and inflows, grew by 459,000 individuals, or approximately 3.8 percent. This population growth has occurred despite a relative decline in the number of low-paid foreign workers.

Who are foreign dependents?

So what’s causing this difference? To further understand the impact of the government levy on Saudi Arabia’ foreign population, a deeper understanding of who counts as dependents by age group would be worthwhile. Yet, before doing that, let’s make the basic assumption that all non-Saudis who were 19 years and under, as well as those who are 65 years and older, who were out of the workforce and thus living in the country, were considered foreign dependents.

In 2018, these two age groups comprised a whopping 20.7 percent of the total expat population, or one dependent for every five foreigners living in Saudi Arabia. In 2018, these same age groups included 2,618,000 individuals, or approximately 7.8 percent of the Saudi Arabia’s total population.

Beyond providing a good estimate, an additional advantage of these two datasets is that both represent population figures as of mid-2017 and mid-2018. This coincides with the implementation of the foreign dependent levy on July 2017, thus enabling us to assess, with some accuracy, the levy’s impact on the population exactly 12 months after government began collecting those fees.

Oddly enough, the number of foreigners falling into one of the dependent age groups grew between 2017 and 2018 at a rate of 3.7 percent, a rate similar to the growth rate of the overall foreign population. In other words, between 2017 and 2018, the total number of foreign dependents living in Saudi Arabia rose by 93,000 individuals. This raises the question: is Saudi Arabia’s labor market for foreign labor a Veblen good?

Veblen goods and policy implications

In simple terms, a Veblen good is one for which demand increases as price rises. What makes Veblen goods interesting is they violate the basic law of demand, where price and quantity demanded have an inverse or downward sloping relationship. Furthermore, Veblen goods are often viewed as luxury, status-related goods. On these terms, it is hard to argue and measure empirically whether Saudi Arabia’s labor market constitutes a Veblen good without detailed wage and cost data. However, as census survey data has shown us, the Saudi job market possesses some characteristics often associated and observed with Veblen goods. Namely, despite a non-trivial increase in the cost of working in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and living with one’s children or elderly parents, foreign workers continued to bring their dependents to live with them throughout 2018. In other words, the demand for entering and working in the country rises despite an increase in the cost of entry and cost of living in the country.

Additionally, whether or not foreign workers view Saudi Arabia’s labor market as a Veblen good has different repercussions for the policy’s future effectiveness. For instance, if we assume that the policy’s primary objective has been to curb foreign worker flows into the country, then the policy did not accomplish its goals (yet). However, if foreign worker levy fees have been introduced as a way to generate revenues, then in an economist’s terms, Saudi Arabia (as a supplier of its labor market) has been successful in capturing the additional consumer surplus. This policy intent has important consequences on several sectors.

For one, while there is no public data on the distribution of foreign youth between private and public schools in the Kingdom, we can look to data shared by some Saudi private school and property owners. Specifically, before the policy’s implementation, private school owners worried that the fees will cause them to lose consumers since they enroll the majority of foreign young dependents. But the data shows the opposite; in the last 12 months, the number of non-Saudis who were 19 years old or younger increased by 86,000, from 2,327,00 to 2,414,000 youth.

On the other side of the leger, the number of foreign seniors, those who are aged 65 or older, also rose by roughly 7,000 individuals, reaching 204,000 people in 2018. The repercussions of this growth amongst the senior foreigner population using healthcare services in Saudi Arabia are ambiguous due to lack of public data but could also have ramifications for why the Saudi government implemented the levy in the first place.

Ultimately, more data is needed to determine whether or not the Saudi Arabian labor force is a true Veblen good, although preliminary data suggests that it is. In the meantime, the Kingdom should evaluate whether the levy is meeting its goals. On one hand, one may argue that if the objective of the policy introduced in 2017 had been to lower or curb the overflow of foreign workers into the Kingdom, then the policy has yet to attain its goals. On the other hand, if the policy’s primary goal is to operate as a revenue-generating program, then one may reasonably believe that it has already accomplished substantial results, as the foreign population living in the country has increased despite the introduction of the new policy.

Photo by Maher Najm via Flickr (public domain).

Born and raised in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, Meshal graduated three years ago from Cal State University-Northridge double-majoring in accounting and business administration. He then worked for two private companies in projects with the Ministry of Labor and Social Development (MLSD), covering research areas such as unemployment and social mobility challenges in the country. He co-authored several policy whitepapers including Saudi Arabia’ G20 2016 and 2017 responses submitted through (MLSD). In the past three years, Meshal has also worked at a local think tank in Saudi Arabia and co-authored a research paper testing the correlation between a student’s neighborhood location, family’s property value, with their standardized high-school exam test scores. In the future, Meshal would like to continue researching labor market and social mobility in the Kingdom and become the Minister of Labor and Social Development.