Studies consistently show that when women succeed, their communities see high rates of return across many areas. Boys need to be included in female empowerment programs, however, for these efforts to be successful, as their buy-in is key for dismantling the sexism and rigid gender roles that hold girls back.

There is enormous growth potential in girls’ advancement, particularly around education. For example, a one percent increase in the number of women with a secondary education could result in a 0.3 percent gain in per capita income. Furthermore, with an additional year of secondary school, girls can increase their future salaries by 10 to 20 percent. Educating girls also reduces rates of HIV/AIDS, malaria, and maternal mortality.

Despite these benefits, the U.S. Agency for International Development estimates that 61 million girls between the ages of six and 14 are not currently in school. Women and girls, especially those in developing countries, disproportionately face challenges to receiving an education, including household obligations, violence and abuse, child marriage, and little parental support. Even for girls who attend school, a lack of proper sanitation facilities, little to no women’s health education, and sexism in class materials and curriculum can make learning difficult.

Expanding the traditional approach to girls’ advancement

More girls are attending school than ever before, but new challenges have emerged in almost 80 countries, such as low enrollment in primary and secondary school, quality of learning, and gender gaps in math and science.

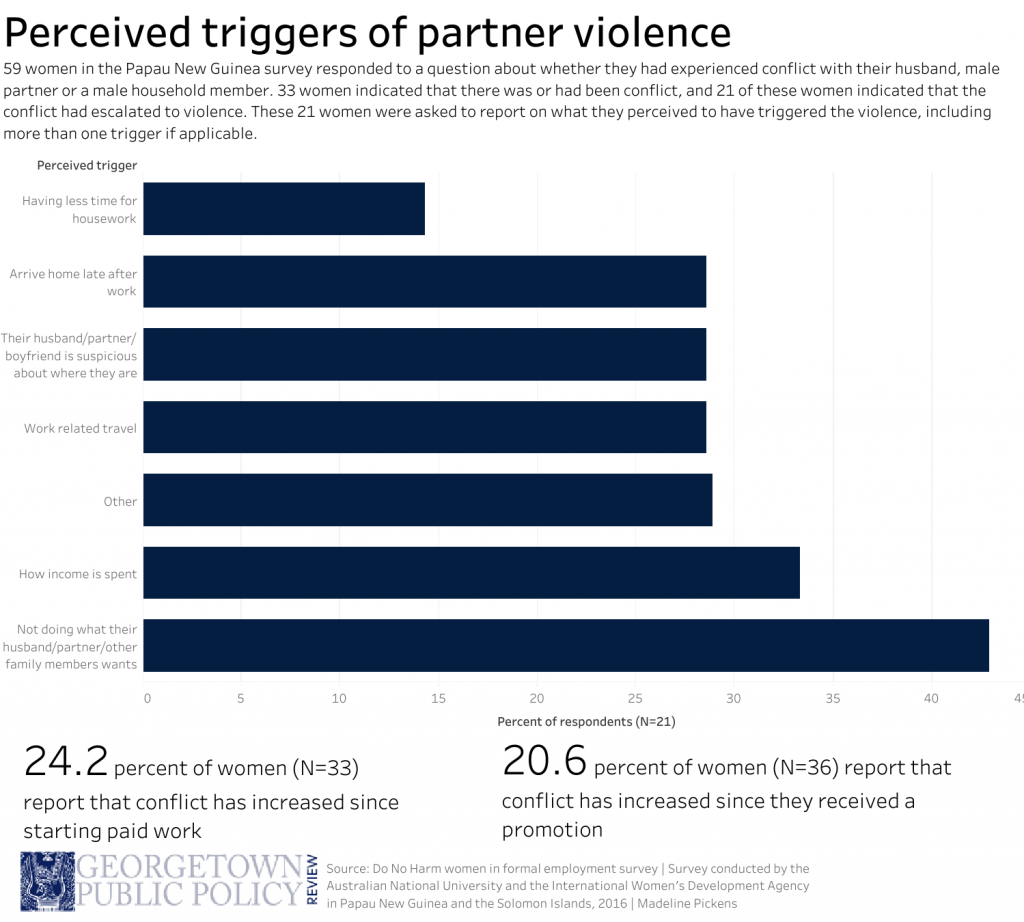

In most developing countries, girls’ advancement typically focuses on practical skill-building, women’s health education, school facilities, learning resources, and leadership opportunities. These solutions, though likely improving educational attainment and future economic prospects for women, are actually not necessarily linked to gender equality. It has been found that improving a woman’s ability to be independent, whether through education or access to credit, could increase danger to her or other women. By challenging traditional gender roles and power dynamics, women-only projects can correlate to increased domestic violence and conflict against women who are perceived as receiving priority treatment. Some research shows a link between female-only micro financing and gender-based violence.

Historically, the discussion around women’s issues often leaves out the roles of men and boys. But, in the past few years, patriarchal cultural norms have become increasingly acknowledged as a relevant barrier to girls’ education. Non-governmental organizations have attributed “changing attitudes amongst men and boys” as one of the primary targets of women’s empowerment projects.

Male inclusion, through school-based trainings, community-level programming, and public information campaigns promoting gender equality, could strengthen the impacts of most, if not all, areas of girls’ advancement programming. In order to empower girls around the world, long-term and wide-scale societal change efforts must include both boys and girls from a young age. Without addressing the core “power hierarchies” and systemic stereotypes that pervade patriarchal institutions, skill-based programs might not have a profound effect on gender equity.

Educating young people on gender equality is time-sensitive and requires high-return solutions quickly. Pressure to engage and educate men and boys on gender equality issues has mounted after a recent United Nations male-female relations survey in the Middle East found a resurgence in anti-feminist views. Experts believe that this pressure will only intensify as physical and financial security threats continue to threaten stability in these communities.

A study in Tanzania shows a clear relationship between the societal treatment of girls and their ability to make their own health and educational decisions. Although only 21 percent of men have a “zero-sum” perspective on gender relations, their support of equality dwindles on a day-to-day level. Sixty-three percent of male survey respondents believe a woman’s most important role is to take care of the home. Furthermore, though females spend significantly more time on household chores than their male counterparts — an average of 30 hours per week versus 12 — only 68 percent of male respondents admit they do less household work.

The mentality that a girl’s value is maximized in the home is deep-rooted and complex — but it can change. The Tanzanian study also found that both men and women believe they, as individuals, have more equitable views on gender than those of their communities. This data can be strategically important to engage men in the gender equality fight, spur discourse in questioning the persistent and potentially irrelevant community norms, and break down long-held attitudes. Including men and boys in advancing girls’ needs requires engaging boys in the conversation, incentivizing respectful cooperation across genders, and having open dialogue about social norms and gender inequalities.

There is potential to break thought patterns through solutions that empower girls to lead, while ensuring that their male family members and friends are making progress alongside them. It is critical to bring boys in at an age early enough to actually effect long-term attitudes and behaviors. Inequitable stereotypes form quickly, and gender attitudes in adolescents are believed to develop by the 10-14 year age range. In many developing countries, particularly in rural environments with limited government services, schools are a breeding ground for gender-based violence because they often serve as the first venue for boy-girl interaction after discriminatory attitudes are adopted. But at the most basic level, schools are for teaching, broadening minds and challenging viewpoints. Research shows that less educated men are more likely to have discriminatory views on gender or perpetuate physical violence against females in their families. Therefore, improving educational outcomes for boys, before they become partners or fathers, can help block stereotypes from forming and mitigate their negative effects on girls and women.

Including boys works

When paired with girls’ empowerment programs, boy-focused training yields significant impact. A 2016 Engendering Men review found that gender equality programs are most effective when men and boys are encouraged to take on household chores and challenge widely-held beliefs on masculinity. Targeting solutions that focus on these outcomes not only reduces violence against women, but also benefits male educational attainment and health. The organizations involved in the review – Promundo, Sonke Gender Justice, and MenEngage Alliance – believe that achieving gender equality involves work from both genders, from 100 percent of the world’s population.

Early childhood development programs in schools and clubs that educate young men on childcare and household work have been successful in improving familial gender relations. Promundo’s involvement in Tanzania has demonstrated that children who see mothers and fathers sharing responsibility in the home while growing up are more likely to expect and express equal roles in their adult relationships. Encouraging boys and men to help women with domestic work has an intergenerational effect – 45 percent of men whose fathers helped with household tasks in their childhood also perform these tasks now, as compared to only 29 percent of those whose fathers did not assist in the home.

In Nepal and other parts of South Asia, the Gender Equity Movement in Schools has been proven to be an effective intervention to start the conversation on gender equality at the classroom level. The program focuses on self-reflecting, understanding equitable relationships between boys and girls, questioning violent tendencies, and reevaluating social norms. The program has seen positive results in changing gender attitudes, reducing discriminatory behaviors, limiting violence against girls, and improving the overall perspective on girls’ education.

Today’s students are rapidly becoming our future global workforce – by 2030, 25 percent of the world’s talent will come from India. Groups like the Equal Community Foundation (ECF) are seizing control over statistics like these and raising Indian “boys to demand girls’ rights” through community-based training for young boys on how they can support girls and women in their communities. Data collected from ECF’s Action for Equality Graduate Program is telling — in self-reflection, 85 percent of male participants believed they had personally improved as a result of the program. Observations shared from the boys’ relatives reflected participants’ personality changes including less anger, improved listening, increased confidence and ambition, and a higher willingness to intervene in family disputes.

Why male integration in women’s issues is unpopular (and difficult)

Addressing the crux of the girls’ advancement issue is an ambitious task that requires creating a new normal and redefining masculinity – helping men see that they aren’t giving away their own power by providing women opportunity and teaching boys to advocate for their sisters, mothers, and friends. Though the impact of boy inclusion in girls’ advancement has been tried, tested, and proven, it remains a relatively unique approach in the development context.

Across funders and field organizations alike, male integration in gender equality can be unpopular because of its perception – men saving women, boys stunting girls’ growth, and money moving away from girls-focused work to include a less marginalized population. Skeptics may believe that male support for women’s equality can generate a male victim conversation that further perpetuates anti-feminist thought.

These arguments portray a man’s role in gender equality as that of a “savior” and assumes that women and girls can be the only drivers of the gender equality movement. However, this perception is often untrue; in fact, male involvement is complementary to women-led projects. From a funding perspective, it is important to make the distinction between cross-cutting programs and new programs. Additionally, in more dire cases of marginalization, male allies are strategically important to achieving gender equality. Rather than losing focus on girls’ issues, strategic decision-making is a key aspect of addressing the needs of disenfranchised groups while avoiding cultural resistance.

Empowering women is always the key, the point, the intention. If bringing boys and men along in a constructive and appropriate way further enables that aim, why not support it? When boys are taught to take an active role in supporting women in their communities, we get closer to attaining a gender equitable society and having positive impact on future generations.

Looking ahead to broad change

Gender equality is a long-term issue that won’t be achieved without dismantling stereotypes and adopting new norms. As such, a single development project or a short-term program intervention aimed at improving girls’ education through boy inclusion won’t effect long-lasting change. We must support policy interventions with the potential to affect societal change at a regional or national level.

Policy goals should focus on leveraging ongoing gender equality efforts and fostering partnerships to scale up successful projects across federal and local governments, community-based NGOs, and the private sector. In the immediate, governments can raise national awareness of the issue through proven mass-media engagement strategies. In Ethiopia, intervention providing boys with a combination of group education and community engagement was successful in raising broad support for gender-equitable norms. Engagement policies can promote standardized community dialogue in a variety of ways, including through gender-focused theater and dance, community workshops, condom distribution, and dissemination of printed educational materials, like newsletters, at a regional level.

In the long-run, governments can combat gender stereotyping through the creation of public-private partnerships, rural-urban networks, and nationwide public information campaigns. For example, the Tanzanian government could design a marketing campaign based on Promundo’s findings on the difference between an individual’s views on gender inequality and those of their community. Building a mass-media campaign around this gap is an example of the “social-norms-theory,” which reinforces gender equality as the prevailing social norm, because more people believe in it than you may initially expect. This policy approach has been proven successful in changing attitudes about topics that are often not challenged at a national level. One-off programs are often not broad enough to unpack sexist attitudes beyond the short-run, but coordinating efforts across areas may lead to a higher adoption on a wider scale.

Photo by Apiradee Chappanapong via Flickr.

Rikita is originally from the San Francisco Bay Area and graduated from UC Davis in 2016 with degrees in economics and international relations. She previously worked as a finance management consultant at PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the strategic partnerships manager at the Asante Africa Foundation. In early 2018, while conducting research-based fieldwork with a non-profit organization in rural India, Rikita learned firsthand the heightened development challenges rural communities face, particularly in regards to lack of access to markets, institutions, media, and education. Rikita plans to work in the rural education space after graduation, specifically in evaluating impact of rural access programs.

I’m surprised an article on gender equality completely ignores the gender binary and employs extremely binary language when talking about gender. It fails to address that gender and sexual identity minorities from countries outside if the US are often seeking asylum in the US because of how the patriarchy negatively impacts them when compounded with their identities — which neither patriarchy nor the feminism idolized in this article recognize.

I guess my question is why such a blatant disregard when the crux of the article is to advocate for broad change?