In this article in our online series on Rethinking Governance, GPPR Online Editor Aruj Shukla explains why the World Bank’s new Human Capital Index is a policy game-changer.

It is almost impossible to conceive of a time in human history better than today. The number of people living under extreme poverty has dipped to record lows, the global middle class is booming, average life expectancy has increased, and more children are going to school across the world.

These enormous strides towards the betterment of the human condition could well afford governments and the international development community a hard-earned sense of complacency. However, with the release of The World Bank’s Human Capital Index (HCI) in October, complacency is a luxury that the world cannot yet afford.

Human capital, or an individual’s collective skill-set and knowledge to create economic value, plays a fundamental role in economic growth and is a keystone to development. Modern levels of progress would not be possible without investments in health and education – the primary drivers of human capital development. Although physical capital investments traditionally dominate international development conversations, human capital also plays an important role in productivity and innovation. However, there are barriers to investing in health and education. Compared to physical infrastructure, health and education payoffs are less tangible and take longer to become visible to the average voter, if at all. Such attributes make investing in human capital less politically feasible for policymakers, and less attractive to aid agencies, non-profits, and international financial institutions. To overcome some of these barriers, the Human Capital Index is a timely and effective tool.

The Human Capital Index

In its simplest form, the Human Capital Index (HCI) measures the productivity and human capital potential of children in each country, given optimal health and education conditions. For example, if a country’s current conditions hold steady, children in this country born today with an HCI value of 0.62 would only realize 62% of their maximum productivity. In other words, the prevailing standards of health and education would cost said country 38% of its national income. The HCI quantifies economic losses from sub-optimal investments and their returns on human capital. As a result, it is a valuable resource for citizens and governments to chart their nation’s path to growth and prosperity.

A rehashed human development index?

Quite like the Human Development Index (HDI), the HCI is an aggregate index encompassing child mortality and life expectancy, quality of learning and education, and health. However, two indices notably differ in approach to well-being. The HDI takes a multi-dimensional, rights-based approach to development and moves beyond gross domestic product (GDP) and per capita income (PCI) to measure developmental progress. In contrast, the HCI takes a hard-nosed economic approach to measuring the essential aspects of human capital development and how they factor into productivity and economic growth. By ranking countries based on the level of human capital that children can expect to attain by age 18, contingent on their country’s health and education standards, HCI aims to reconcile measurement issues of multi-dimensional growth with that of economic theory.

HCI: an outcome-oriented index

HCI emphasizes outcomes, not investment dollar amounts. Traditionally, governments, aid agencies, and philanthropies have assumed that “more investment means more spending.” While higher expenditure may have yielded better outcomes in health and education in the past, the same might not hold true today. Using modern measurement standards, the HCI forces policymakers to address many distinct issues, including school quality and infrastructure, to increase human capital. The HCI’s outcome-oriented approach presents two profound challenges for policymakers: first, how to evaluate and maximize the impact of spending and second, how to improve the quality of public services, especially health and education.

The use of learning-adjusted years of schooling (LAYS), a singular metric that combines quality and quantity of schooling, to measure education outcomes is an innovative and important step. LAYS aligns with development economist Lant Pritchett’s view that “schooling is not learning,” by incorporating learning outcomes — and not merely years of education — when assessing the quality of education. Without taking learning outcomes into consideration, students could spend decades in classrooms to approach the same levels as their peers in countries with higher learning outcomes. Yet again, the HCI demonstrates the importance of reforming systems to provide quality education and healthcare.

India’s rejection of HCI

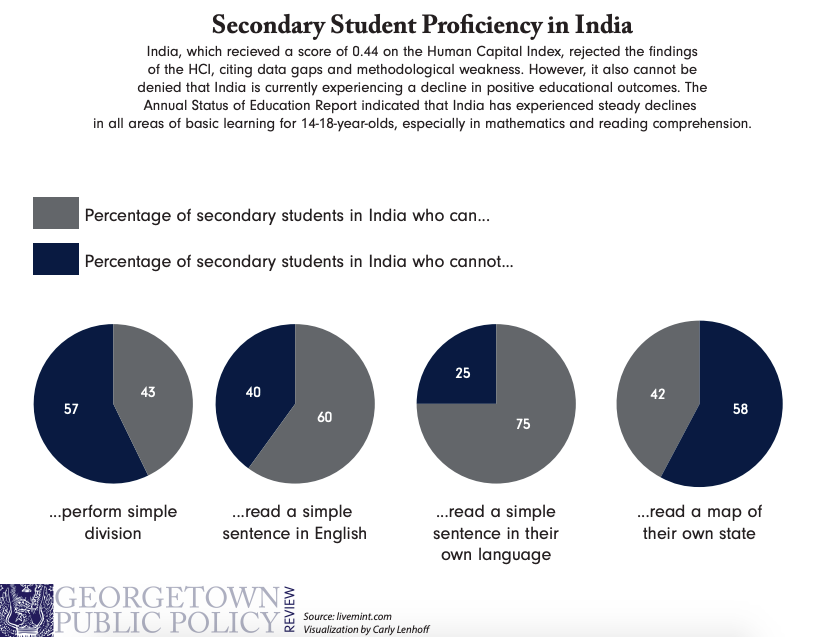

Within a few days of the release of the HCI — in which India received a score of 0.44 — India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) publicly announced the government’s decision to ignore the HCI due to data gaps and methodological weaknesses. While no index is perfect, the decision to completely ignore the HCI findings is potentially disconcerting.

India’s low HCI score — especially compared to nations like Vietnam and Kenya with similar or lower GDP per capita — is a consequence of poor health and education outcomes despite high levels of economic prosperity. The Annual Status of Education Report (ASER), which assesses basic learning outcomes, also indicates a steady decline, especially in math, across almost all Indian states in the past decade.

As the ASER also indicates dwindling learning outcomes, the Indian government’s rejection of the HCI ultimately highlights the enormous levels of political will necessary to overcome the status quo and invest effectively in the future’s workforce productivity. The objective nature of the HCI provides the citizens of India with the toolkit and political incentives to hold their government accountable for better outcomes in health and education, including bridging the data gaps that the BJP has pinned its disregard for the HCI on.

Long-term growth implications

Owing to the changing nature of work – and therefore the development challenges due to automation and institutional changes in labor markets – the need to re-examine global human capital development and economic growth is more pressing than ever. The HCI is a quantifiable tool to help policymakers consider ways to improve productivity and prosperity. Besides allowing citizens to hold their governments accountable, the HCI could guide governments in more efficiently allocating resources.

The long-term growth implications of a universal, standardized index to measure human capital are immense. As endogenous growth theorist Robert E. Lucas noted, “The consequences for human welfare involved in questions like these are simply staggering: once one starts to think about them, it is hard to think about anything else.” The HCI is a mere nudge for policymakers to get off on the right foot.

***

Photo by nevil zaveri via Flickr.

Aruj is from New Delhi, India, and previously worked for a social enterprise dedicated to delivering development solutions across India. Aruj majored in materials science and engineering from NTU, Singapore, and before his stint in in the development sector in India, he worked as an engineering consultant in the Oil & Gas sector in Singapore. After McCourt, Aruj plans to work in international development, doing policy research and impact evaluations especially in the area of nutrition, education, and employment.