As cyber weapons become more accessible and versatile, many states are incorporating cyber into their national defense strategies. What does this mean for nuclear proliferation, especially for non-state actors and states such as Iran post-JCPOA?

President Donald Trump recently announced the withdrawal of the United States from the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), otherwise known as the Iran deal. The Obama administration negotiated the JCPOA in 2014 in order to delay Iran’s nuclear program. With America leaving, the world is now discussing the possibility of Iran resuming its nuclear weapons program.

But there is one type of weapon that is possibly even more dangerous than a nuclear bomb: cyberspace. On the first day of this year’s annual Herzliya Conference in Israel, former head of Mossad and current president of the cybersecurity startup XM Cyber Tamir Pardo explained that a cyberattack targeting civilian nuclear reactors could cause Chernobyl-style meltdowns without firing a single shot. In addition, he said a cyberattack is a “soft and silent” nuclear weapon because cyberattacks leave no easily traceable “fingerprints.” The time it would take to react to such attacks may be far too long to effectively retaliate or otherwise respond. One may point to the alleged 2007 Russian cyberattacks on Estonia or North Korea-linked WannaCry ransomware attack of 2017 to illustrate this difficulty; in both cases, the states affected by these attacks offered only rhetorical retaliation while the damages ended up costing billions of dollars.

The nuclear threat of cyber

In 1997, the President’s Commission on Critical Infrastructure Protection reported that a cyberattack could not have a “debilitating effect on the nation’s critical infrastructures,” but may cause “serious damage and disruption” as infrastructure facilities increasingly rely on online systems. Since then, there has been talk of “weapon of mass disruption” to describe the danger of cyber weapons. Indeed, North Korea has created a “cyber army” to carry out thefts and extortions of banks and other foreign private entities.

However, cyber weapons also have the ability to cause mass destruction and states may use them in offensive actions against others. One threat is that of hacking into nuclear weapons systems to steal secrets and even attempt to carry out nuclear attacks. There have been 23 cyber incidents in nuclear facilities since 1990, 11 of them “intentional.” Although these incidents mostly involved stealing data and disrupting systems, the Stuxnet virus attack caused physical damage to the Iranian Natanz Nuclear Facility and the TRISIS virus, which specifically targets nuclear facility safety systems, has recently been detected in the Middle East. Efforts to acquire increasingly destructive cyber weapons has led to a cyber arms race.

The accessibility of cyber

With accidental meltdowns as reference points, one might infer that a cyberattack that causes a meltdown would cause long-term human suffering and damages amounting to billions of dollars. The Chernobyl and Fukushima disasters both exposed thousands to radiation and still weigh heavy on the Ukrainian, Belarussian, and Japanese budgets, while the towns in closest proximity to the ruined reactors remain abandoned. A cyberattack targeting, for instance, the India Point Energy Center (a nuclear plant near New York City), has the potential to significantly amplify this type of destruction.

Unlike nuclear weapons, anyone can use cyberspace for malicious purposes with just a computer and the right know-how. In the words of cybersecurity and counterterrorism expert Dr. Gil-Ad Ariely, knowledge is a “thermonuclear weapon for terrorists in the information age,” and cyberspace is a “habitat” for knowledge that may be useful to terrorist groups. With this habitat open to anyone with an internet connection, cyber capabilities are relatively easy to acquire even for private individuals.

Another factor making cyber more accessible is affordability. Operations in cyberspace require little to no blood and treasure, nor the need to cross any border, enabling malicious actors to cause massive damage at low cost. One may look to the alleged Russian interferences in the U.S. presidential elections and U.K. Brexit referendum for illustration; Russia may well have swayed domestic politics in foreign countries without firing a single shot. This cost-effectiveness is the reason that even poorer developing countries are now investing in advancing their cyber capabilities. The low financial cost of acquiring and using cyberspace maliciously allows not only states, but also criminal and terrorist organizations to access cyber weapons. One may even say that nuclear weapons are already in the hands of anyone with Wi-Fi and a computer.

The versatility of cyber

As knowledge is a thermonuclear weapon and cyberspace is a habitat for knowledge, so too is cyberspace itself a versatile nuclear weapon if one uses it as such. That is, one may employ a cyber weapon to cause minor damage or bring down whole societies, to conduct a precision or indiscriminate attack. In addition, the hard-to-trace nature of cyberattacks renders the conventional reluctance to use nuclear weapons a nonissue.

These factors make cyber weapons usable as controllable tactical nuclear weapons or hydrogen bombs alike. A large-scale attack may shut down an entire country’s infrastructure; a smaller-scale strike may cause a single nuclear plant meltdown. If states and organizations adopt this method of warfare, a revolution in military affairs may occur that changes the way wars are waged.

Cyber, Iran, and a solution

Whether or not Iran gets the bomb, those wishing to discourage or even perhaps render obsolete its proliferation may seek to invest in cyber capabilities. The aforementioned 2010 Stuxnet attack – attributed to Israel’s elite Unit 8200 – successfully destroyed Iranian nuclear centrifuges. This most likely not only set back Iran’s nuclear program, but also sent a strong message to Iran that proliferation will be costly. Further development of cyber capabilities and increasingly advanced cyber weapons like Stuxnet in the hands of countries like the U.S. and Israel will help deter and, later, render useless proliferation. Indeed, as cyber capabilities advance, general reliance on sophisticated high-tech facilities will increasingly become a vulnerability, undermining the deterrent value of nuclear weapons.

The U.S., as the world’s “default power” and principal keeper of the global nonproliferation regime, may well find it beneficial to lead the push toward greater cyber capabilities. At the moment, the Trump administration may consider refocusing from creating a “space force” to allocating more budget toward developing a “cyber force.” Creating more cyber units and emphasizing computer science in military academies are steps the U.S. can take to realize this goal.

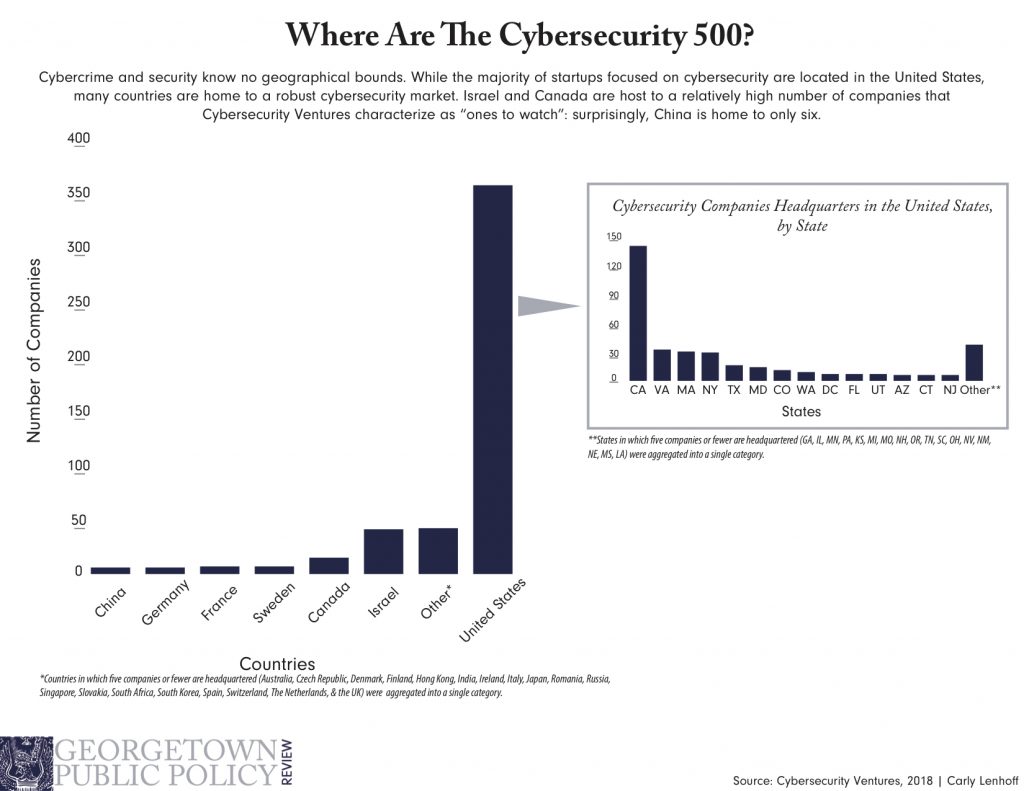

Israel, with its conflict with Iran and rebranding from “startup nation to cyber-nation,” has the capability and incentive to intensify its pursuit of cyber capabilities. In the private sector, Israel has over 420 active cybersecurity companies (second only to the U.S.) that raised almost $1 billion last year, making up 16 percent of cyber investments worldwide. Pardo’s company, XM Cyber, is one of the companies that are part of this burgeoning market and will help ensure future cyber will not go out of control, just as today’s nonproliferation regime aims to do for nuclear weapons.

With the world looking for ways to stop Iranian proliferation in the wake of the American withdrawal from the JCPOA, it may be time to focus on developing cyber capabilities. The U.S. and Israel should lead this effort toward ultimately creating a strong cyber arsenal for NATO. At the same time, we should be aware that cyber weapons may become more dangerous even than nuclear weapons in the future. Thus, the U.S. and Israel should develop strong cybersecurity alongside cyber weapons to ensure the latter do not become uncontrollable.

***

Photo by Richard Patterson via Flickr.

1 comment

[…] to react to such attacks may be far too long to effectively retaliate or otherwise respond. – Georgetown Public Policy Photo by Richard Patterson via […]

Comments are closed.