Research agrees that “the typical volunteer is white, female, married with children, middle-aged, with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status.” But are they straight, too? This first article in the Invisible in Data series about LGBTQ communities explores that question. This article is excepted from a larger work that may be accessed by contacting the author at chw47@georgetown.edu.

Background

Almost 70 percent of people in the United States support homosexuality, and roughly 60 percent of people in the United States support same-sex marriage. These statistics reveal that despite recent attacks on the lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) community, acceptance of LGB people continues to increase. Indeed, acceptance proves critical to providing people, especially marginalized communities, the ability to publicly integrate and exist in society after centuries of inequities. Acceptance gives rise to individual feelings of belonging and fosters civic engagement behaviors. For example, academic research about lesbian women’s sociopolitical involvement finds that a sense of belonging to the LGBT community strongly relates to sociopolitical involvement in LGBT communities.

The question

One form of civic engagement, volunteering, continues to draw the attention of researchers. Particularly, researchers concern themselves with the demographic and economic determinants of volunteering. Researchers continue to include in their analyses many demographic and economic variables: gender, race, birth status, military service, education, income, marital status, age, employment status, homeownership, and parental status. Remarkably, the research tends to agree that “the typical volunteer is white, female, married with children, middle-aged, with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status.” But are they straight, too?

This article used results from a correlation matrix (not shown) to determine that sexual orientation correlates with variables typically considered in regressions for volunteering. Marital status and parental status correlate the most with sexual orientation, in a negative way (roughly a -0.15 correlation), suggesting a negative correlation between being a sexual minority and marriage or having kids. Thus, the exclusion of sexual orientation results in omitted variables bias, as this article demonstrates.

The model

The data for this analysis come from the General Social Survey’s (GSS) 2012 and 2014 rounds, as sexual orientation and volunteering variables only appear together in these two years. GSS collects survey responses from adults 18 years or older living in households in the United States using random probability sampling. GSS interviewers from the National Opinion Research Center at the University of Chicago conduct the survey in person. GSS contains smaller sample sizes than other surveys such as the Current Population Survey, increasing the difficulty of finding statistical significance in results due to larger standard errors. GSS remains one of few publicly available surveys that collects sexual orientation data, which it began collecting in 2008. After applying probability weights, the sample size for the two models (see the ‘LGB Model’ and ‘Interaction Model’ in Table 1) including sexual orientation comes to: n = 1,166. The LGB model adds a sexual orientation variable into the Original Model, while the Interaction Model adds a sexual orientation variable as well as two interaction terms into the Original Model. Since the most complete model of the three in Table 1 is the Interaction Model, the marginal effects of that model are of most interest here. The regression equation for the Interaction Model is:

The outcomes

Table 1 (below) shows the results of three separate regressions. The arrows in the table indicate the directional changes in the numerical value of the beta coefficients moving from the original model to the interaction model. Joint-significance testing using the Wald X2 determined overall statistical significance of all three models (Original Model X2 = 58.86; LGB Model X2 = 47.59; Interaction Model X2 = 49.10). All Wald statistics report statistical significance at the p < 0.05 significance level. The original model reports that Nonwhites volunteer more than Whites. The LGB model (second model) generated a a △-0.121 in βRace causing a change in the sign of association from positive to negative. Then, the inclusion of interaction terms led to only an additional ▵-0.003 in βRace. Without the sexual orientation the race variable would produce incomplete results contrary to past research. The model without accounting for sexual orientation produced Type IV error. The null hypothesis posits no association between race and the likelihood of volunteering exists. However, the original model shows evidence that Nonwhites volunteer more than Whites, but the second and third models counter with evidence that Nonwhites volunteer less. This indicates Type IV error because the original model produced “statistically correct” results that ultimately were undermined by other contrary “statistically correct” results.

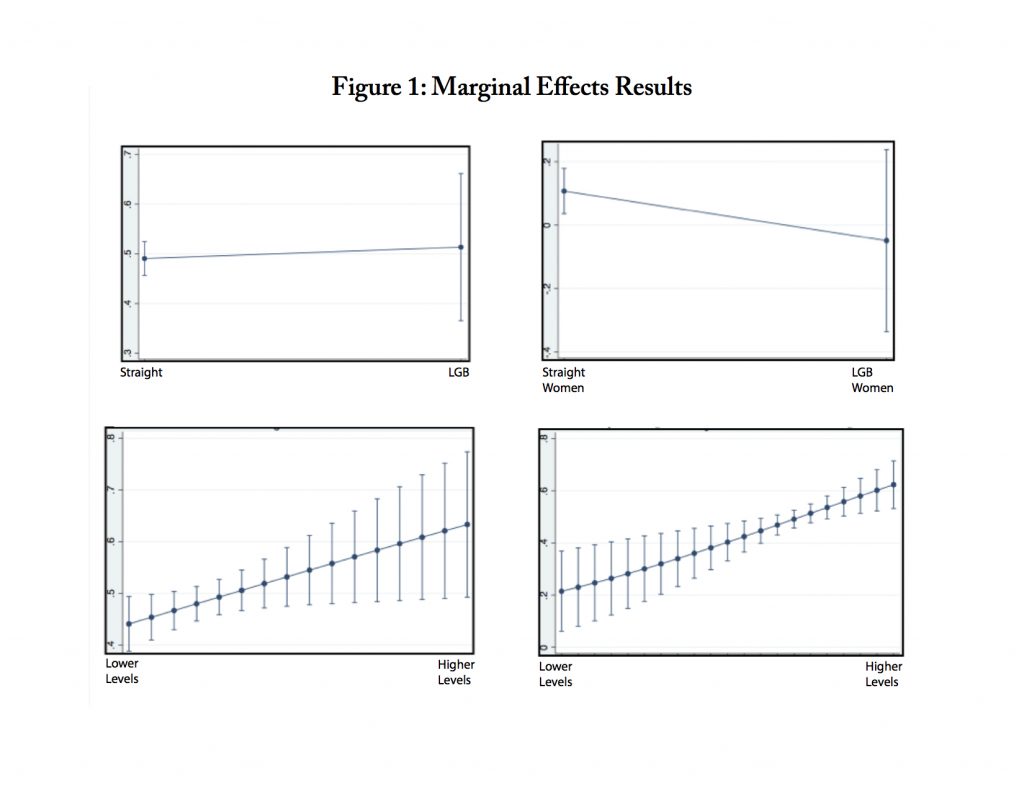

Figure 1 shows key findings of a brief post estimation. The first graph shows that sexual orientation predicts the likelihood of volunteering with statistical significance, though no differences in volunteer patterns between LGB and non-LGB people. The second graph accounts for sexual orientation in the marginal effects of gender on volunteering, showing that while gender plays a role in straight women’s volunteer patterns, it bears no statistically significant impact on lesbian or bisexual women. That is, gender serves as an impetus of volunteering for straight women, but not LGB women. The third and fourth graphs show that accounting for sexual orientation confirms that both income and education positively relate to volunteer patterns in statistically significant ways. That is, while the more educated appear to volunteer more than the less educated, those who earn more appear to volunteer no more than those who earn less.

The takeaway

The typical volunteer is white, female, married with children, middle-aged, with higher levels of education and socioeconomic status — and apparently both straight and LGB. The inclusion of sexual orientation further underscores the serious need for the collection of sexual orientation and gender identity variables. Omitted variable bias comes in various forms, and the exclusion of one’s sexuality takes on both a social and methodological characteristic of bias. After years of living in the closet, LGB people now enjoy some rights such as marriage. However, much to learn about the LGB community remains. Now that LGB people may feel as if they can come out of the closet, social scientists must venture for data in the unknown and start mining in it.

***

Header photo from www.humanengineers.com