Advocates of taxpayer-funded political campaigns often claim that such systems improve the political process by exposing incumbent politicians to more competition and increasing the chance that challengers will defeat them in elections. One such advocate, the Brennan Center for Justice, has argued that tax-financed campaigns “improve competition, and help challengers.” Lower incumbent re-election rates in states that offer tax-financed campaigns would result, as competition rises.

Evidence shows no such result. The evidence available indicates that, despite claims that this policy increases electoral competition, taxpayer financing of political campaigns does not produce statistically significantly lower re-election rates for incumbent state legislators. A comparison between states with and without such laws suggests that the system of funding campaigns has no effect on re-election rates. Many factors contribute to high incumbent re-election rates across states, such as name recognition, the platform provided by elected office, and voter satisfaction with their representatives. Tax-financing of campaigns is not one of those factors.

Analysis

At the state level, it is not uncommon for incumbents to run unopposed in a primary or even general election. It is also well-established, that incumbents win re-election in the vast majority of races. Many factors can make primary or general elections more competitive, such as partisan composition of districts, but incumbent re-election is the norm. Supporters of public financing argue that providing taxpayer money to campaigns makes races more competitive. They base this claim on a belief that doing so would theoretically reduce the cost of entering a political race for less well-funded candidates. Tax-financing requires fewer voluntary donors to trigger a larger amount of campaign funding. However, even if more candidates run under tax-financing systems, changing the composition of government requires winning elections. It may not make sense to call elections more “competitive” if incumbents can still easily defeat challengers. If tax-financing systems genuinely increase electoral competitiveness, as supporters claim, we should see lower rates of incumbent re-election in states with taxpayer-funded campaigns.

To analyze the impact of taxpayer-funded campaigns on competitiveness, consider the percentage of incumbents in all state legislatures from 2010 to 2016 that won re-election. States are divided between those with taxpayer-funded campaign programs for state legislators (Arizona, Connecticut, Hawaii, Maine, and Minnesota) and those without such programs. Incumbent re-election rates were calculated by dividing the number of incumbents who won their primary and general election by the total number of seats up for election, subtracting the seats with no incumbent. The results indicate that the difference in incumbency rates between states with taxpayer-funded campaigns and those with solely private funding is statistically insignificant.

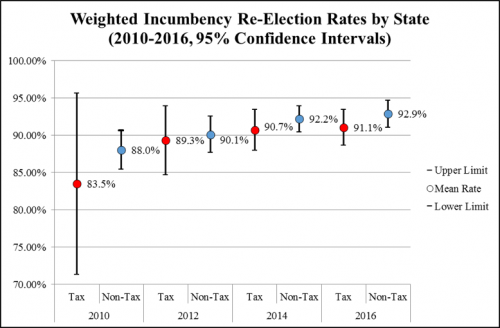

Below is a graph showing the average incumbency rates of the two groupings of states (tax-financing and non-tax-financing) per election cycle. The intervals represent, with 95% confidence, the range of expected election results based on the data. The results demonstrate that both groups of states have high incumbent re-election rates each election cycle, with statistically insignificant differences between them.

On average, incumbents in states with taxpayer-funded campaigns won their primary and general elections at a rate of 88.7% from 2010 to 2016, while those in the other 45 states won at a rate of 90.8% – a difference of just 2.1%.

Although supporters of tax-financed campaigns argue that they yield more competitive elections, the gap in incumbent re-election rates between the two state groups tends to be narrow and noisy. In each cycle, the differences within each group of states overshadowed the differences between groups. In 2016, for example, the difference between the highest and lowest incumbency rates was 7.7% for tax-financing states and 42.9% for non-tax-financing states.

There are a few potential reasons why tax-financed campaigns yield no significant reductions in incumbent re-election rates. One is incumbent name recognition, which forces challengers to spend more money to introduce themselves to voters. Funding for tax-financed campaigns, which is usually distributed in some facially equitable manner, fails to overcome this and other advantages of incumbency. Despite claims to the contrary, public financing schemes could constrain the ability of challengers to quickly raise the funds necessary for candidates to disseminate their message to the electorate.

Another possibility is that taxpayer-funded systems encourage challengers who are unserious, disliked by voters, or even actively trying to exploit the system for their own gain. Such candidates might have a much harder time finding support from donors on their own, even though they are still able to qualify for public money.

Conclusion

Genuine political competition requires that incumbents bear a greater risk of defeat at the polls, but this rarely happens in states with taxpayer-funded campaigns. As this analysis demonstrates, states with tax-financed campaigns see comparable incumbent victory rates in primaries and general elections to states with privately-funded campaigns. This is in spite of the fact that tax-financing states attract more electoral challengers.

It is possible that there are other factors at play contributing to both high incumbency rates and the differences between states. Such factors, including unique political cultures or economic conditions in specific states, are beyond the scope of this analysis. Future research could examine more variables or conduct a longitudinal study of election results before and after tax-financing programs were instituted.

Regardless, these results pose a problem for advocates of taxpayer-funded campaign systems. If such laws fail to change the composition of legislatures or give challengers a significantly better chance of winning office, they risk spending taxpayer dollars for results that are identical to those in states with privately-funded campaigns. Policymakers should therefore be skeptical of claims that taxpayer-funded campaigns will increase political competition or reduce the overwhelming, built-in advantages that incumbents possess in elections.

This article is a modified version of an Issue Analysis originally released by the Institute for Free Speech in June 2017.