Just as anti-trade sentiment in the U.S. contributed to the election of Donald Trump, similar concerns have created friction and fragmentation across the Atlantic. In addition to the obvious threats Brexit posed to the EU model earlier this year, populist and nationalist fervor manifest in opposition to the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) and the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership (TTIP) have brought renewed scrutiny to the efficacy of the EU. Although Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and European Commission President Donald Tusk officially signed CETA on October 30th after overcoming the opposition of Belgian local governments, TTIP continues to face intense opposition as the final components of the agreement are settled upon. The premise of transatlantic trade with the EU is facing the tripartite threat of renewed nationalism, rising internal localization, and an intense wave of populism across Europe.

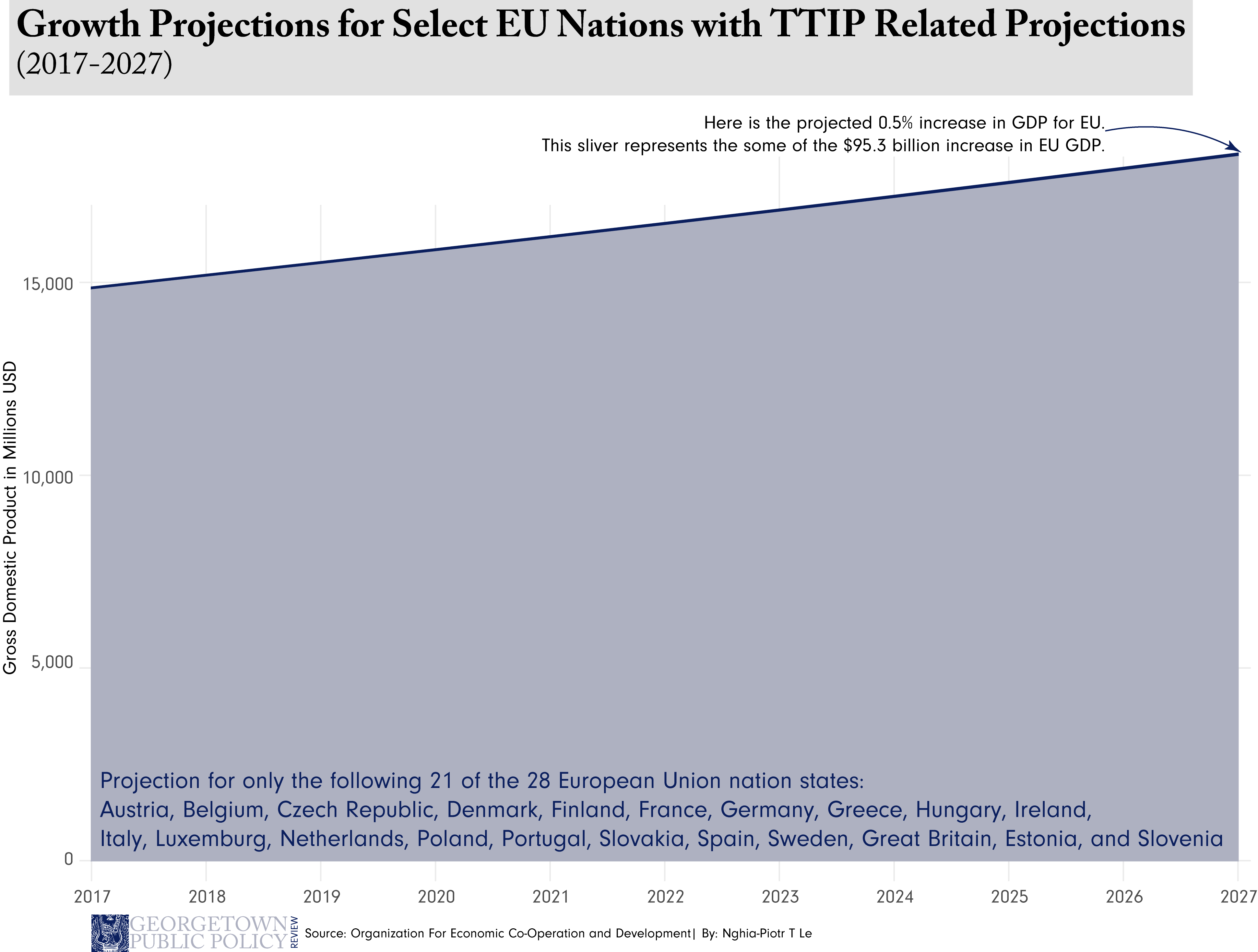

The macroeconomic benefits of trade agreements like CETA and TTIP have been completely drowned out by protests over income distribution effects. Although EU member states stand to gain a reported aggregate increase in GDP of 0.5% and an added income of $95.3 billion by 2027 from TTIP, the deal has met intense resistance. Opponents cite the impact TTIP could potentially have on geographic exclusivity over products like parmesan and champagne, as well as on fair labor and environmental standards. Similarly, although CETA would create 1 million jobs and save EU exporters an average of $548 million per year according to EU officials, critics claim CETA and TTIP would limit the ability of member governments to challenge foreign multi-national corporations (MNCs) with lower labor and environmental standards and over-privatize government functions central to public welfare.

In particular, heightened populism has manifested as intense opposition to one specific component of the CETA and TTIP agreements: the Investor State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) system. According to the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative, the ISDS is an international arbitration body that aims to “provide an impartial, law-based approach to resolve conflicts” between MNCs, EU member state governments, and the other national party to the agreement (Canada in the case of CETA and the U.S. in the case of TTIP). While various forms of ISDS have been part of 3,000 international trade agreements, civil society organizations across Europe are now denouncing the ISDS as a pernicious body that will put the interests of MNCs over the health, safety, and environmental standards of EU members.

It is important to note that TTIP is still under negotiation, and therefore any discontent is based on discussion points from successive rounds of negotiations that will not necessarily factor into the final text. As the Spokesperson and Head of Press and Public Diplomacy Section for the Delegation of the European Union to the United States James Barbour emphasizes, “we don’t have [an agreement] yet, so it’s very difficult to be for or against TTIP; it’s very difficult to talk about ratifying or not because we’ve had a number of negotiating rounds but we will have a number more.” One key concession of the earlier CETA negotiations was the addition of an Investment Court System (ICS) that would include an appellate body and judges not appointed by dispute parties. EU negotiators will likely make similar concessions in the final text of TTIP.

The ability of individual citizens to impact trade agreement negotiations has been heightened by decentralization. Based on the “mixed agreement” protocol afforded to EU member states, it is not just national governments that must approve the trade agreements, but the many regional parliaments within EU member states as well. For this reason resistance from the Belgian region of Wallonia was poised to derail CETA until the European Council agreed to exempt the region’s agricultural sector from full liberalization. Localities in EU member states like Belgium and the Netherlands approve trade agreements like CETA only through popular referendum, which is often hostile to transnationalism. Given that the trade agreements will undoubtedly have different effects on each region depending on industrial specifications, this feature of the EU legislative process creates significant challenges for any free trade agreement championed by the European Commission.

Decentralization in Europe has only heightened the political weaponization of the populism sweeping across every EU member state. The nearly 3.5 million European citizens who signed petitions rejecting both TTIP and CETA have also responded to the effects of trade agreements on immigration and income inequality by rejecting any policy, party, or candidate that seems to place transnational integration over the well-being of their country’s own people and companies. The rejection of the trade agreements is part of a broader wave of support for populist parties in European countries like Greece (Syriza party), Poland (Kukiz’15), the United Kingdom (Independence Party), France (National Front), Spain (Podemos), the Netherlands (Party for Freedom), Denmark (Danish People’s Party), Germany (Alternative for Germany), Austria (Freedom Party of Austria) and Slovakia (People’s Party-Our Slovakia) that reject European integration, budgetary austerity, and open migration policies. While the national parliaments in countries like Germany and the United Kingdom still remain almost entirely comprised of non-populist legislators, parties like the Alternative for Germany and the Independence Party have made strong gains at the regional level within the two countries. This has left European leaders struggling to champion the benefits of progressive trade liberalization while simultaneously combating these powerful movements towards economic isolation and local .

Despite pessimism brought on by Brexit, challenges to TTIP and CETA, and populist surge, there is reason to believe the transnational body can rebound. Brexit does not present a death knell to regional economic integration, and the recently concluded CETA may present a template for an EU-UK trade agreement finalized by 2019. The EU also recently concluded an agreement with Vietnam and is moving closer to a final agreement on a deal with Japan that would offer significant market opportunities to European exporters. Even as some prominent officials pronounced the TTIP dead, a group of EU member states including Finland, Britain, Italy, Spain, Portugal, Ireland, the Czech Republic, and others sent a letter to the European Commission urging forward movement on negotiations with the U.S. Despite the election of a supposedly anti-trade President-Elect across the Atlantic, the European Commission has proven on several occasions that compromise presents a plausible way forward.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/295797672″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]While more compromises no doubt must be made for the U.S. and EU negotiators to salvage the fate of TTIP, it is up to both U.S. and EU officials to effectively communicate to respective citizens the value of free trade. As Barbour admits, “It’s very easy for those of us on the policy side to think that everyone knows that free trade is great, [but] we need to explain better to constituents that we are taking their concerns on board as we craft these agreements.” It is about communicating that member states will still have power to regulate standards that serve the public interest, and that trade agreements do not give MNCs limitless power over sovereign member states. With the right communication strategy, EU and US officials can prove that TTIP and CETA are part of the right response to the populism currently sweeping the Western world.