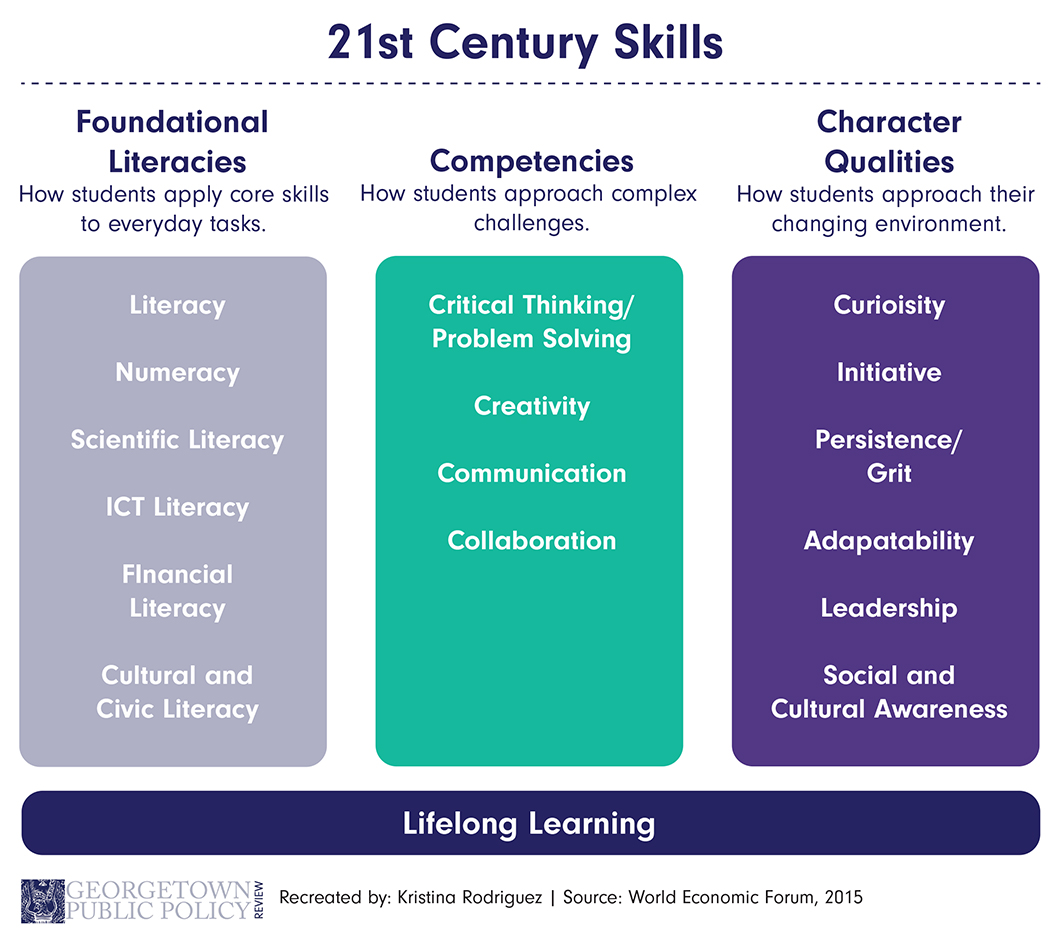

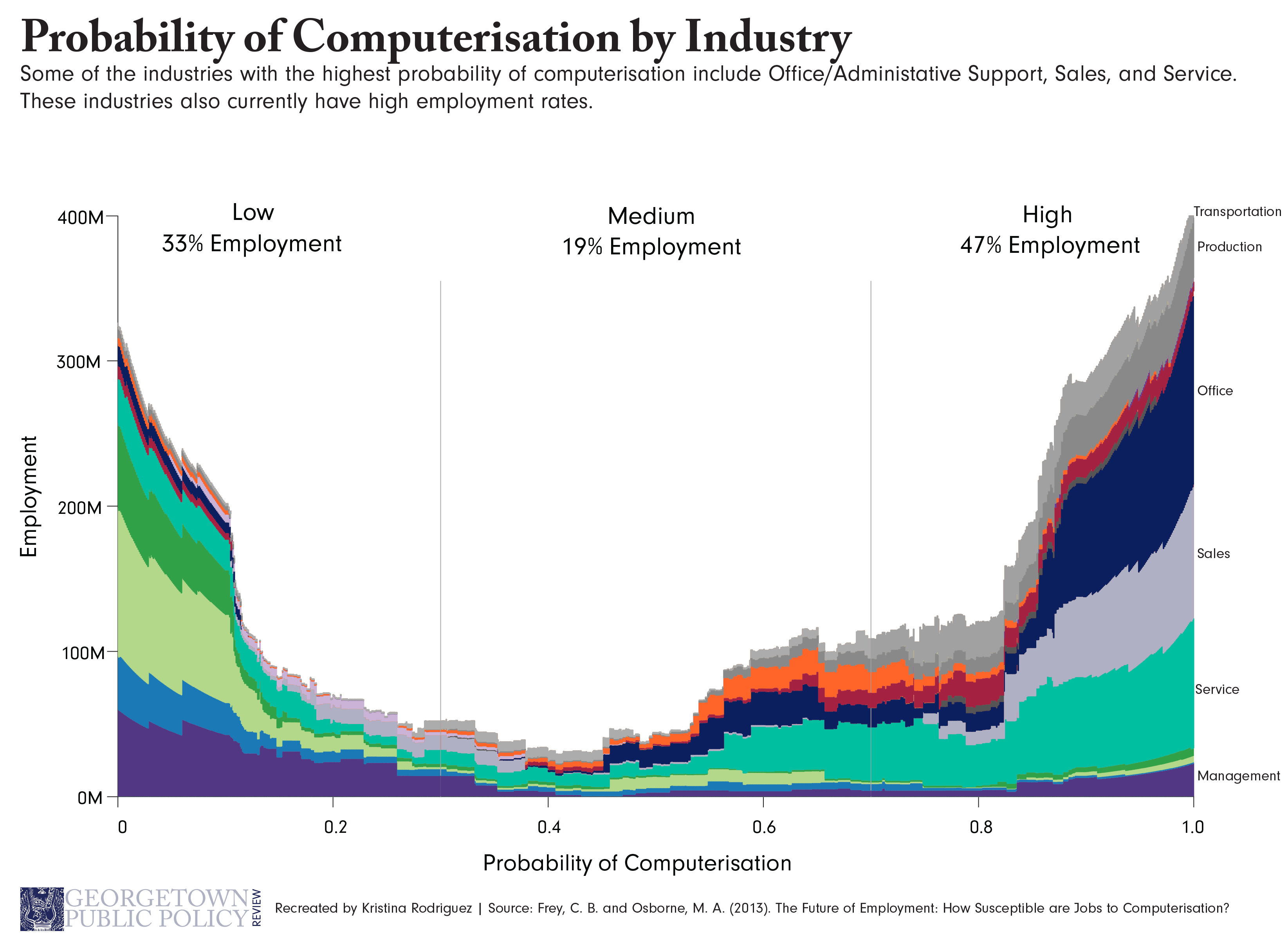

In part one of this two-part series on technological automation and 21st century learning, we discussed how robotics, software, and machine learning are replacing human jobs at an unprecedented pace. The automation of blue and white collar jobs over the next few decades requires a different approach to skill building beyond STEM training, and focuses on how human soft skills can best augment AI to create innovative design and add value to the global economy. While many governments across the world have refused to accept the future of work by instead investing in short-term vocational trade, subsidizing fading industries, and directly rejecting automation, others are initiating a re-return of soft skill training that may ultimately soothe the pessimistic concerns of technological nihilists.

The slew of 21st century skills and abilities described in part one are only valuable insofar as they can be taught or transferred. Some have argued soft skills like grit, interpersonal communication, and problem solving can only be learned through experience, and curriculum reform to better emphasize these non-cognitive skills is futile. However, there are a small number of individuals and organizations rejecting this disheartening axiom, and attempting to disrupt the traditional model of cognitive knowledge transfer in many classrooms across the globe.

Early Childhood Development

Research by James Heckman and others has shown the importance of the first few years of a child’s life in the development of both cognitive and non-cognitive skills, and the likelihood of future economic success. These findings have inspired preschool intervention programs like Colombia’s Escuela Nueva aiming to to build non-cognitive skills like problem-solving and critical thinking during the most formative years of neural development. Countries like Finland are even creating entire models of early childhood education centered around the concept of “play,” often incorporating computer modules to fuse non-cognitive skill development with modern technology. In China, officials previously associated with the country’s one-child policy are now turning their attention to parent training centers that aim to teach parents how to play with their children in a way conducive to non-cognitive skill development.

Design Learning

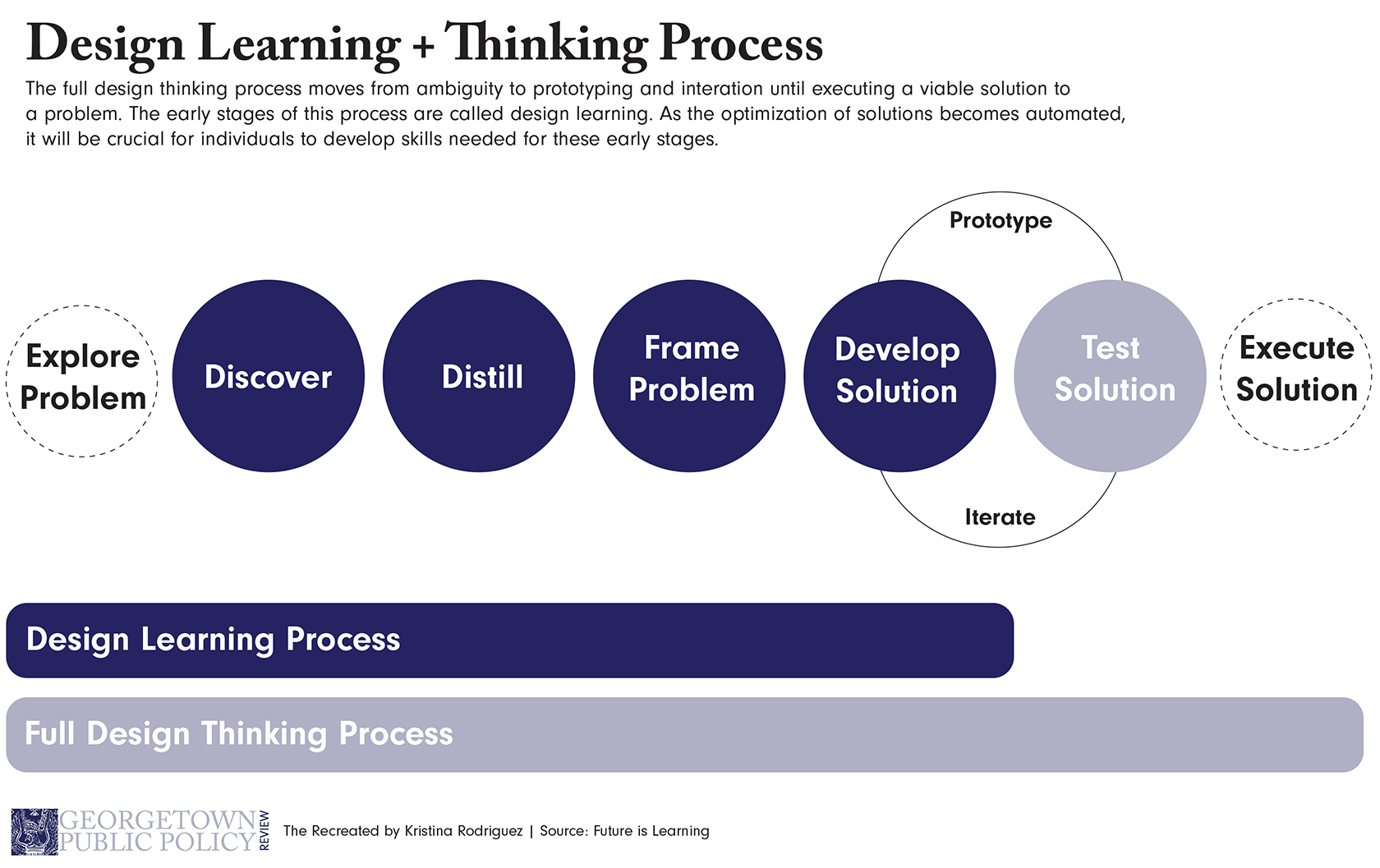

Product managers and policymakers have traditionally employed design thinking to actively engage consumers and constituents in exploring new ideas aligned with market desirability, technical feasibility, and economic viability. The approach involves shifting from a passive relationship between producer and consumer, whereby innovators identify underlying issues and prescribe dynamic, adaptable ideas. Design learning rests on the assumption that innovative processes are moving so quickly that learning skills aligned to the current workforce is a futile activity.

According to Daniel Araya, author of the upcoming book Augmented Intelligence: Smart Systems of the future of work and learning, “The whole process becomes so fast that there is no value in being a part of it. The only way to stay ahead is to create and design.” Educators should reject the notion that education is only meant to help students find jobs and instead prepare them to create jobs. To ready students for the future of work, policymakers, educators, and entrepreneurs will soon be causing disruption by applying “the very same dynamics that transformed the taxi and hotel industries [to] transforming the education system,” said Araya.

Shifting away from passively transferring fixed knowledge is at the heart of design learning that is slowly being grasped by innovative post-secondary institutions. For example, Becker College in Massachusetts uses the label “Agile Mindset” to describe a curricular approach built on problem solving and divergent thinking, entrepreneurialism, project collaboration, and social and emotional intelligence. The Kanbar College at Philadelphia University is implementing a transdisciplinary framework emphasizing non-cognitive entrepreneurial skills built upon group projects and problem solving. IDEO, the global design firm run by design thinking guru Tim Brown, has even made a comprehensive toolkit for “Design Thinking for Educators,” available online to teachers and curriculum designers around the world.

As the workforce increasingly shifts to augmented relationships between humans and AI, there will be an increasing need to prepare students at all levels with the soft skills needed to respond in innovative ways to inevitable change. However, because many local officials and school administrators in the U.S. and elsewhere remain focused on addressing educational inequalities with the provision of basic education in poor districts, there has been no real systematic effort to integrate design learning within curricular frameworks. While individual teachers around the world continue to take advantage of open access resources to tailor lessons to the design thinking approach, these efforts remain sporadic and underfunded.

Phenomenon Based Learning

Arguably the most innovative approach to soft skill education is Finland’s Phenomenon Based Approach. Finnish schools are switching from completely subject-based learning (i.e. math, social studies, language arts, etc.) to a cross-discipline, topical curriculum that incorporates multiple cognitive and non-cognitive skills into one class period. The idea is that real life topics and scenarios are not confined to just one academic discipline but incorporate skills across multiple subjects. For example, a student can embark on a project focusing on architecture incorporating traditional subjects such as mathematics, economics, geography, as well as non-cognitive skills such as teamwork, problem solving, design, and project management.

The shift in focus is coupled with pedagogical changes pushing students to engage in collaborative projects centered around creativity, critical thinking, communication, and collaboration (the four C’s). Finland’s approach puts students in the often challenging position of developing ideas with minimal advice, and guiding projects from start to finish. Students often end up focusing on topics requiring significant creative innovation, providing students the opportunity to sharpen skills like grit, adaptability, and leadership.

According to Helsinki’s education manager Marjo Kyllonen, Finland’s goal is for all schools in the country to incorporate phenomenon-based teaching into their curricula by 2020.

Entrepreneurial education

With almost half of U.S. jobs expected to disappear in the coming decades according to a 2013 Oxford Martin School study, a few educational institutions are beginning to shift curricula from preparing students to get jobs to training students to create them. Because it is far more difficult to measure how well students are learning soft skills like opportunity recognition or persistence, many educational institutions have chosen instead to pour investment into STEM skillsets that can be measured through standardized testing. In the era of augmented intelligence, however, entrepreneurial education can be used to develop creative innovative capacities through technological aptitude and change resilience.

Given the paucity of research to draw from, educators in various countries have experimented with different methods to teach entrepreneurialism. Organizations like Noble Impact are partnering with K-12 schools and local businesses to blend academic curricula with entrepreneurial and non-cognitive skill development. The government of Buenos Aires successfully embedded entrepreneurial training academies within public schools around the city, and has begun implementing empirical evaluation schemes to tie the results of these initiatives to future policymaking. The Network for Teaching Entrepreneurship (NFTE) is working with schools in countries like China and Japan to teach students about entrepreneurial practices and mindsets. Although research remains unclear as to whether entrepreneurialism can be taught through traditional education – whether entrepreneurial “grit” can be taught is a particularly difficult question to answer – it is clear to some that the skills of figured like Steve Jobs and Jeff Bezos can indeed be cultivated in school classrooms.

The Return of Liberal Arts and Civic Education

As the salaries of software programmers and app developers rose to new heights over the past decade, some policymakers have advocated for shifting resources away from liberal arts and civic education and towards hard-skill STEM training. Organizations like the American Chamber of Commerce focused on developing a talent pipeline whereby students at primary, secondary, and tertiary levels would learn STEM skills desired at innovative technology and engineering firms. While there is no doubt skills like coding and mechanical engineering remain valuable assets for employment in the present, there is a legitimate fear that reforming curricula in this way means schools are teaching students skills that will be automated in the near future.

Advocates of a re-focus on liberal arts have been vocal in their pursuit of reform. In 2015, Fareed Zakaria published In Defense of a Liberal Education, in which he aligns the curricula of liberal arts programs with 21st century skills like systems design, critical thinking, problem solving, and interpersonal communication. In an open letter to the American people, former Associate Justice to the U.S. Supreme Court Sandra Day O’Connor and former U.S. Senator John Glenn advocated for increasing the role of civics education in classrooms to develop a future workforce bent on promoting social impact. To cite a specific example of implementation, Florida State University has redesigned its liberal studies program to focus on the value of civic education in promoting a curriculum focused on logical thinking, adaptation and innovation, and problem solving.

Project-based learning

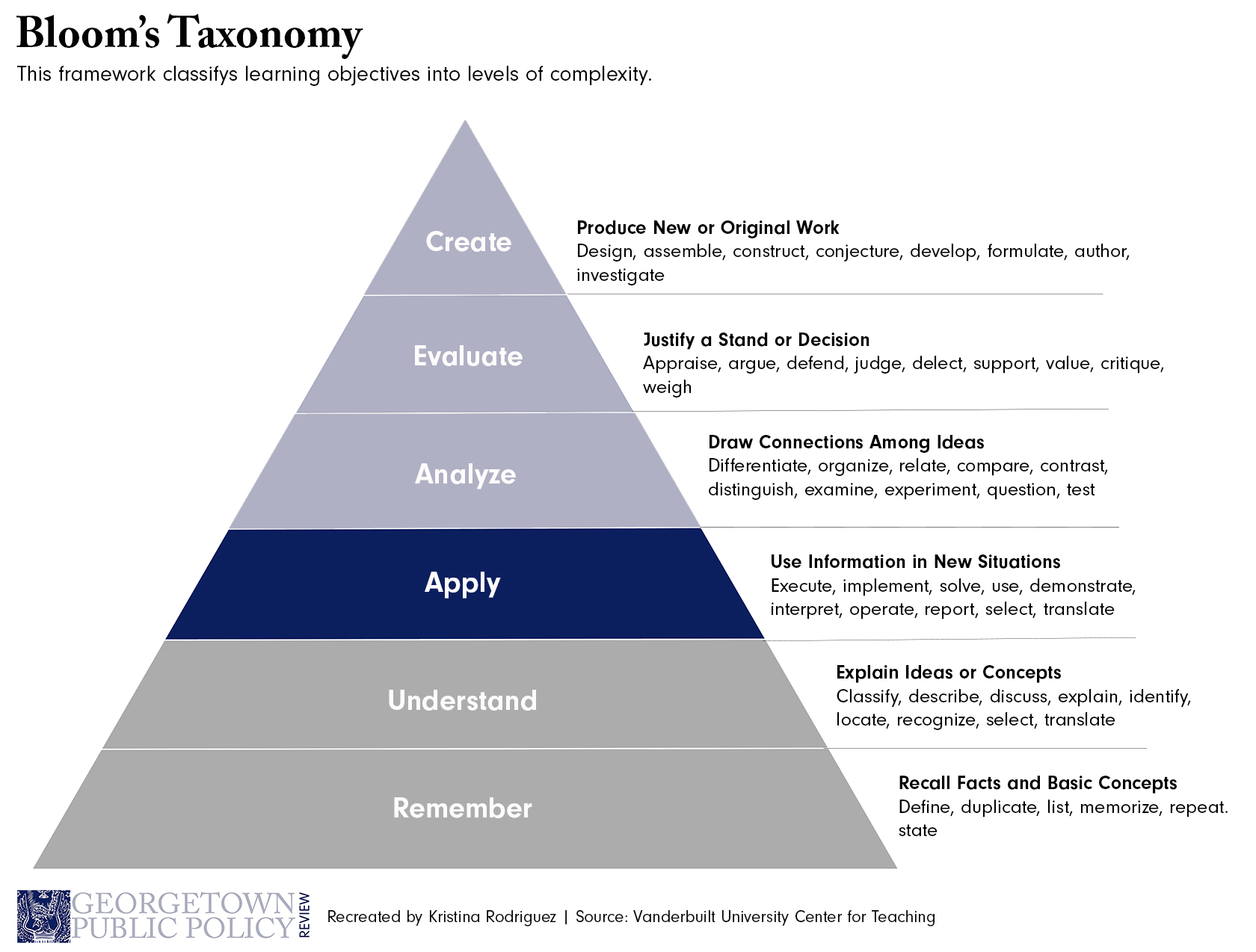

Teachers at many K-12 classrooms around the U.S. have reduced the amount of time they lecture in class, preferring to completely shift that form of instruction to virtual out-of-classroom modules. Under this model teachers act as facilitators and project managers, providing students with scenarios, case information, and answers to logical questions that slowly elevate students to new levels of knowledge application and evaluation. Instead of spending 45 minutes lecturing students about a z-score or a student’s t-distribution, teachers instead group students to build research proposals or analyze fieldwork findings.

Not only does project-based learning reserve precious classroom time for the higher rungs of Bloom’s taxonomy, it also encourages the development of non-cognitive skills. By providing students with the guidance necessary for self-driven project-based learning, teachers can steer the development of soft skills such as interpersonal communication, information adaptation, and time management.

For example, Concordia University in Portland, Oregon, has begun employing Google’s “Twenty-Percent Time projects” to drive students to conduct every phase of the project management process – from pitching and setting the timeline, to establishing goals and milestones and presenting results. The logic behind these projects is to use 20 percent of class time every day to provide students complete freedom in selecting a topic and developing a project around that topic. Simulating the creative processes of large technology companies like Google and IBM within K-12 classrooms can provide students with the analytical thinking and adaptive leadership that will be crucial in the augmented intelligence world of the 21st century.

Moving Forward

Find what works

While several studies have highlighted the value of non-cognitive skills for future employment, few have captured how soft skills like social intelligence and computational thinking can effectively augment intelligence. Convening groups of practitioners, academics, and policymakers to carry out evidence-based analyses of what works can create a stronger impetus towards experimental pilot programs that do not remove STEM education from classrooms, but instead blend existing curricular structures with innovative pedagogical approaches to non-cognitive learning.

Organizations like the Aspen Institute and the World Economic Forum have already created commissions to examine filling the pending skills gaps through soft skill education. The argument for empirical research into the value of non-cognitive learning is compelling as the decoupling of economic productivity and labor growth currently presents a real threat to many economies across the world. Further research at both the school and firm level is needed to assess which soft-skills are most vital to the 21st century labor market, and what the most effective ways of teaching those skills are.

Move up the taxonomy

To ensure students are not simply learning soon-to-be-automated hard skills, schools should begin removing fixed knowledge transfer from the in-class lesson plan. That is not to say spending time learning about covalent bonds, is not valuable, but that spending limited in-class hours focusing on the “remember” or even “understand” rung of Bloom’s taxonomy is a waste. The market is now flush with competitive education technology platforms that computer-savvy students can use outside the classroom to learn the basic concepts they will need to subsequently apply, analyze, evaluate, and create through interactive student-driven projects in the classroom.

This is not a brand new realization. Minerva School in San Francisco has completely removed fact transmission from instruction time and reserved class time for sharpening communication and collaboration skills through project-based learning.

Change the Four-Year Education Model

The higher education model of four years of isolated lecture is outdated. While there are no doubt colleges and universities incorporating greater project-based learning and student collaboration into curricular programs, there is little acceptance of the value of apprenticeship programs, public-private partnerships, or virtual platforms that disrupt the traditional tuition-based model. As students struggle to connect what they are learning at the university level to employment that will not soon be automated, they will need greater incentives outside of the traditional four-year framework. Breaking down the institutional model where students spend most of their time in the classroom through engaging innovative firms for collaborative opportunities will encourage students to develop the entrepreneurial skills vital in the 21st century.

Conclusion

The “great decoupling” of employment growth and economic productivity means educators can no longer look to present market demand to determine what students should be learning. Instead, governments and educational organizations must take a more prescient approach to education that provides students the soft for when technological innovation inevitably consumes the routine hard skills characteristic of modern industry. What’s more, transferring heavily experiential skill sets to the next generation of students and workers requires a new approach to pedagogy that elevates the teacher from a regurgitator of static facts, to a guide of project development and human-centered design.

STEM-focused education should not be replaced entirely by project-based learning that pushes students to conjure projects out of thin air with little understanding of related concepts. Instead, the era of augmented intelligence requires educators and policymakers to take those hard skills and drive students to deeper understanding through application and evaluation. Understanding how those traditional disciplines can be leveraged in conjunction with a range of other subjects to drive solutions to market demands and social needs is at the heart of augmented intelligence.

Christian Conroy is currently a dual Master in Public Policy (MPP) and Master of Science in Foreign Service (MSFS) candidate at Georgetown University, where he is focused on using econometric analysis to advise foreign companies entering emerging markets. Prior to Georgetown, Christian held several positions in the private sector, including Supply Chain Security Risk Analyst at BSI Group, Technical Advisor for Psychometrics and Analytics at GSX Inc., and Shanghai GM at CRCC Asia. Christian was also previously a Fulbright Fellow based in Xi’an, China, where he studied the decentralization of education policy with a focus on the distribution of authority between county bureaus of education and primary schools in rural China. His policy interests include technology disruption, smart city solutions, international development, big data, and just about anything related to China. You can find him on twitter @christianmconro.

What a timely approach to education. I applaud this exciting way of capturing the mind and spirit of students to prepare for disruptive innovations that the world of automation is swiftly bringing into reality.

Please share any thoughts you might have as to how your approach could be implemented into the culture and curriculum of a community college

Hello admin, i must say you have hi quality content here.

Your page should go viral. You need initial traffic only.

How to get it? Search for; Mertiso’s tips go viral