The fight for DC statehood may have finally reached a tipping point

As the young United States of America emerged from the shadow of its Revolutionary War and took its first steps as a new nation, the momentum to expand beyond thirteen former colonies took on an immediate urgency. In 1796 Tennessee applied to become the 16th state in the Union; the first federal territory to do so. The requirements were relatively simple – approve a state constitution by public referendum and demonstrate the capacity for self-governance. Tennessee, having met these criteria, was admitted to the union through an Admission Act requiring a simple Congressional majority vote. No constitutional convention nor ratification by the existing states was required. Tennessee was the first to implement this “fast-track” path to statehood. Now, elected leaders in the District of Columbia hope to mimic the same model.

The push for a truly independent “New Columbia” is not recent, and has in fact been present in political deliberations since the founding of the nation. Out of consideration for the safety and autonomy of the President and Congress, the framework for a federally controlled seat of government was put forth in Article 1, Section 8 of the U.S. Constitution, and mandates that “Congress shall have Power To… exercise exclusive Legislation in all Cases whatsoever, over such District (not exceeding ten Miles square).” New territory was ceded from Maryland and Virginia to establish this capitol, but with this shift in territorial control residents of the new District of Columbia suddenly found themselves bereft of Congressional representation.

Nearly 200 years ago, President James Monroe noted that “As [Congress’ exclusive power over the District] is a departure, for a special purpose, from the general principles of our system, it might merit consideration whether an arrangement better adapted to the principles of our government and to the particular interests of the people may not be devised which would neither infringe the Constitution nor affect the object which the provision in question was meant to secure.”

With the urgency of the 2016 election upon us, Mayor Muriel Bowser has found the ideal opportunity to make a renewed push for D.C. autonomy and will present the issue of statehood to the American people.

The fight for autonomy

The quest for autonomy has always been central to the character of the District. The 23rd Amendment to the Constitution, which gives DC residents the right to vote for President, was ratified in 1961 after a political struggle that dates back to the late 1800’s. Later, inspired by the successes of the civil rights movement, DC’s rising civic leaders – led by future Mayor Marion Barry – pressed Congress to give up their absolute authority over the Capitol. In 1973 these efforts paid off, and Home Rule was established. Under this Act of Congress, an elected city council and mayor were finally empowered after a century of appointed federal officials running District affairs. However, Congress retained the power of oversight and the veto over local legislation and budgets.

The closest DC has ever come to full autonomy was in 1978, when a Constitutional Amendment establishing two Senators and a voting Representative (but keeping Congressional oversight in place) was passed by Congress but failed to obtain the necessary ratification from state legislatures within the seven-year time limit. Throughout the 1990’s and 2000’s there were various efforts to give DC a single vote in the House of Representatives, but advocates failed to make any major inroads. Mayor Vincent Grey even began a campaign to lobby state legislatures around the country to vote in favor of a statehood amendment (should it ever come across their desks).

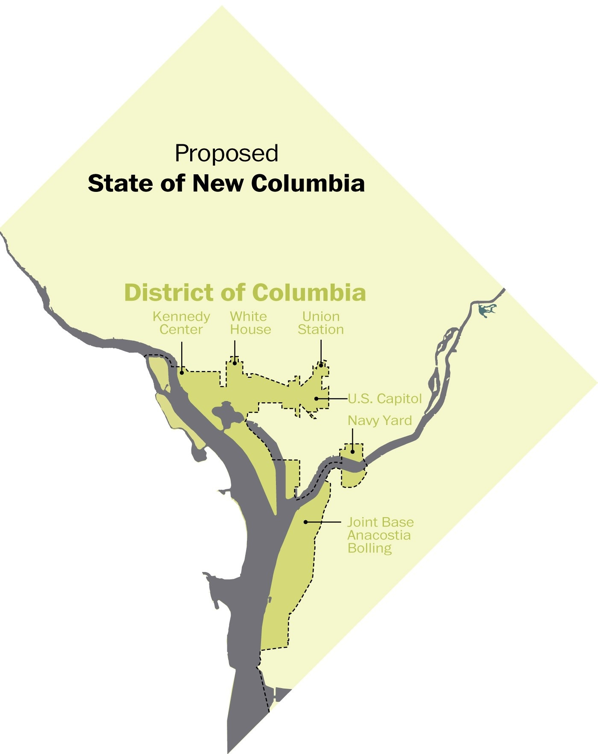

This election day, residents of the District of Columbia will have the opportunity to vote on a ballot initiative that would split the territory into two separate entities – the state of “New Columbia” which will effectively encompass all residential areas, and a significantly reduced federal territory which will include only federal buildings, national monuments, and military installations. Under this proposal, the original Constitutional intent of an independent federal jurisdiction will remain intact.

If brought into the Union, New Colombia (the proposed name of the new state) would be the smallest state by far in terms of area. However, advocates are quick to note that the population of the District (around 670,000) currently exceeds that of either Wyoming or Vermont. Furthermore, the federal tax revenue paid by residents exceeds that of eighteen other states.

Congress

Like Tennessee, D.C. could easily achieve statehood through a simple Admission Act approved by majorities in the House and Senate. The Mayor and City Council of the District of Columbia have demonstrated ability to self-govern since Home Rule was passed in 1973. Since then, D.C. has been plagued with financial woes primarily stemming from its unique territorial status. Presently, the government of D.C. is expected to provide services equivalent to those of a city and a state despite the lack of comparable means financing those programs via taxation or budgetary authority. Furthermore, the disparity between D.C.’s small size and its plethora of public spaces and buildings gives it a distinct disadvantage compared to other states able to levy property taxes. Consider all of the tax-exempt properties within D.C.’s borders – federal buildings and spaces, universities, parks, houses of worship, embassies – and you get a sense of how little revenue is available.

The true Congressional hang-up over D.C. statehood is political in nature. Since the passage of the 23rd Amendment in 1963, the Democratic candidate has won overwhelmingly in every single election (in 2012, Barack Obama walked away with 91% of the District’s vote). The prospect of two more de-facto Democratic Senators and another Democratic vote in the House is an understandable non-starter for the Republican Congress, regardless of whatever civil rights arguments can be made. In the past such partisan divides have naturally brought about the admission of multiple states at once, with the intention of balancing out factional interests. In the first half of the 19th century, the question of slavery in new territories led Congress to admit Maine and Missouri simultaneously. One hundred years later, conservative Alaska and liberal Hawaii shared a similar bond. The other obvious candidate for statehood, Puerto Rico, tends to have a more multi-partisan political landscape and could complement D.C. in a similar manner.

Among Members of Congress who are not particularly inclined to back the creation of the 51st state, one alternative solution has been “retrocession.” Under this proposal, the smaller federal District of Columbia would remain intact and the residential areas, instead of forming their own state, would rejoin Maryland.

Congress has the authority to adjust the actual physical territory of the District of Columbia, and has done so in the past. In 1846 Arlington and Alexandria, originally part of the District, were returned to Virginia after residents argued that the territory was not needed to maintain a functioning federal government (it should be noted that the actual intent of this move was to add more pro-slavery delegates to the Virginia State Legislature).

Although this solution would provide District residents with the full rights that statehood guarantees, such a measure would also require the approval of both the DC and Maryland governments. As residents of both strongly oppose such an action for a variety of reasons (not the least of which being cultural differences that have developed over the past 200 years), retrocession is often talked about in Congress but has little chance of actually moving forward.

The Particulars of the Referendum

Public advocates, led by the New Columbia Statehood Commission, have been working to build public awareness and support for the cause. Last June District leaders held a constitutional convention for the proposed state, which seeks to retain the character of the current governing institutions and keep most city functions intact. Under the new constitution, the Mayor would become the new Governor and the 13 members of the DC City Council would become representatives in the new state legislature.

Regardless of the outcome of this November’s vote, Congressional oversight over District laws means that the referendum will have no binding legal sway and is ultimately intended as a political move. D.C. laws and the spending of local tax revenue have always been subject to a final yea or nay from Congress, and in the past they have used this authority to intervene in social policy. In 2015 Congress moved to block public funding for abortion services for low-income D.C. residents and also attempted to thwart the District’s successful public referendum on recreational marijuana legalization (though they eventually failed due to a legal technicality).

District leaders, long disgruntled with this lack of democratic control, have found ways to challenge Congressional oversight. During the 2013 government shutdown, then-Mayor Vince Gray declared all D.C. public workers “essential” and kept everyone on the job. This year, Mayor Bowser and the City Council will enact a local spending plan without Congressional appropriation and intend to spend the money unless federal lawmakers try to stop them. In both cases, the Mayors have bet on the fact that any Congressional intervention would greatly increase public support for changes to the status quo.

Downstream Effects

The transition to statehood would not be seamless, as both political and policy issues would arise. Under the new system the Mayor-turned-Governor would have the authority to appoint DC judges to the bench – a power currently resting with the President. DC would also take on the responsibility of paying the salaries of the hundreds of judges and prosecutors that make up the local corrections system. The criminal justice system itself, which is currently a convoluted mix of local and federal law enforcement agencies, prisons, and judges, would require significant consolidation.

New Columbia would also be in the unique position of having the smallest state legislature in the nation. With a total of 13 members, only 7 would have to be successfully lobbied to pass a bill. 9 votes could override the Governor’s veto, and 11 could impeach a fellow legislator.

Because the proposed plan would keep a formal, smaller District of Columbia intact, the thorniest issue would likely be the repeal of the 23rd Amendment. With the new state granted electoral college votes by default, it would be unnecessary (and politically problematic) for the federal District to retain 3 votes as well.

Autonomy falling short of statehood, while meant to address the “No Taxation Without Representation” challenge, would leave the District as a second-tier entity and would not address the fundamental issue of self-determination. The right to vote and to establish locally-elected governments, while seemingly essential to the character of America, are not enshrined in the Constitution but are conferred through statehood. Citizens living in pre-1959 Alaska, Hawaii, and the dozens of other former territories that eventually became states were all once subject to the decisions of federally-appointed officials. Even if DC should gain a Congressional vote, the decisions of local officials would still be beholden to the inclinations of Congress. Only through the conference of full statehood will true representative democracy be granted to the hundreds of thousands who call the District home.

Check out Senior Interview Editor, Kevin Barsaloux’s, interview with DC Shadow Senator, Michael Brown, for his thoughts on DC Statehood.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/286201609″ params=”auto_play=false&hide_related=false&show_comments=true&show_user=true&show_reposts=false&visual=true” width=”100%” height=”450″ iframe=”true” /]

Shane McCarthy (MPP '17) is a freelance writer and former senior online editor at the Georgetown Public Policy Review.

A good read and some interesting facts. I’m not convinced DC should have 2 Senators though. Do the historical motivations for equal representation across states still make sense? How important is state sovereignty? I’d argue the current House vs. Senate balance is not ideal in a post-globalization world/economy. The physical barriers and geographical differences that used to isolate and differentiate states seem to matter less now. To add another low-population state would just further the imbalance.