Introduction:

You might say that immigration in the United States is as American as apple pie. It is woven into our history and a permanent part of our national identity. Yet, public policy as it relates to immigration is another story. Despite widespread recognition of the failings of our current immigration system, comprehensive reform at the national level has stalled for over a decade. Though the past two Presidents, Obama and Bush, signaled support for comprehensive immigration legislation as well as several leading members of Congress—most recently the “Gang of 8” in the Senate—the last major reform package to pass was enacted in 1986. In lieu of national action, states from Arizona to Massachusetts are pushing the boundaries of state jurisdiction to tailor immigration enforcement to their state’s needs while cities from Los Angeles to Louisville are working to improve integration, modify immigrant rights, and cater services to their changing populations. Together, they are reshaping immigration policy and practice in the US in ways never before imagined.

Until recently, immigration policy was predominantly the domain of the federal government in the United States. Since our founding, the Constitution provided the right to Congress to establish rules for naturalization and regulate commerce with foreign nations. With Congress largely deadlocked, however, states and localities are stepping to the fore to meet the changing needs of their citizens as immigrant arrivals ebb and flow, the use of government services shift, and new generational challenges emerge.

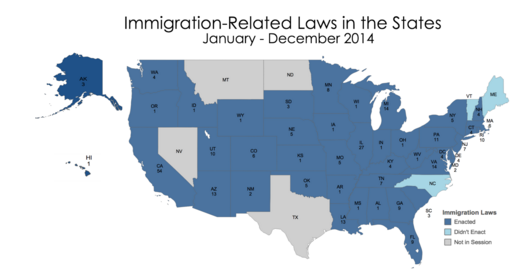

Though states were not expressly empowered by the Constitution to develop policy relative to immigration, they were also not expressly barred from such acts. In fact, states and cities established a long precedence of partnership with the federal government on naturalization and refugee asylum (well before the current debate surrounding Syrian refugees) as well as leadership in regulating benefits and services for immigrants such as healthcare and education. It was not until the mid to late 2000s that states began really testing the boundaries of their jurisdiction on immigration issues and state legislation began to skyrocket. State leadership increased dramatically in the last decade especially. While in 2005 only 38 new laws relative to immigration were enacted at the state level, by 2009 222 laws were enacted in 48 states. After several major and contentious immigration bills between 2010 and 2012, including Arizona’s Senate Bill 1070, new state legislation leveled off with 185 enacted laws in 2013 and 171 in 2014.

These new laws range from regulating human trafficking to expanding the rights of minors to in-state tuition to appropriating funds for naturalization assistance. While some are more contentious, such as granting drivers licenses to non-citizens or requiring employers to use E-verify, others are regarded as practical responses to the shifting needs of the populations these states and municipalities serve. In each case, states and their municipal partners are busy crafting policies to support, supplement, or in some instances, even override federal systems in order to meet evolving immigration-related challenges across the US.

Enforcement:

Momentum for immigration-related policy at the state level built in recent years, and this is particularly true for enforcement laws. The uptick is likely due in part to the economic recession heightening fears of immigrants as competitors for low wage jobs. The increased length of time since the last major federal reforms were enacted, including amnesty, also heightened the perceived need for government action.

With several surges of immigrants into the United States over the last decade especially—including the most recent unaccompanied minors in 2013 and 2014—new pressure to address immigration enforcement emerged. In response, states from Texas to Connecticut to Colorado employed a variety of different strategies to design new laws and engage in enforcement of immigration policies. As the area of immigration policy most expressly reserved for and managed by the federal government, however, these enforcement efforts are some of the most contentious of the new approaches taken by state governments to address their immigration challenges.

Border Enforcement

At the height of the crisis of unaccompanied minors crossing the US border in July 2014, then Governor Rick Perry of Texas took matters into his own hands. On July 21st, he called upon 1,000 troops from the National Guard to better secure the border, claiming criminal groups were capitalizing on the distraction and depletion of resources of US enforcement officials caused by the recent surge of youths from Central America. His actions came as Congress was considering a $3.7 billion request from the Obama administration for more resources to secure the border. With House Republicans voicing strong concerns about approving such an expenditure, however, there was little confidence that more resources would be deployed quickly, if at all, by the federal government.

Since then, Texas lawmakers have been busy debating the merits and working to gain support for more sustained border security run by the state. In the 2015 legislative session, about a third of bills relating to immigration focused on bolstering border security through enabling the state to enforce federal laws and one bill, the interstate border security compact, sought to establish a state-level security force of its own. Though the debate rages on and many of the bills will likely not pass any time soon, momentum for greater state and local involvement to secure the borders is building and not just in Texas. In 2010, the Arizona Legislature instituted a “Joint Border Security Advisory Committee” to, among other things, “recommend methods to increase border security,” and “manage construction and maintenance of the border fence.” It will be left to time and court rulings to define more explicitly the role states and localities may assume with regard to border protection. In the meantime, the immigration enforcement landscape is being reshaped every day by state and local governments particularly as law enforcement officials have, as a practical matter, already begun taking on this role without explicit funding or legislation.

Apprehension and Deportation

Border patrol was not the only area of immigration enforcement that was raised on state and local agendas in recent years. Apprehension and deportation of undocumented immigrants already within US borders also emerged on clerk dockets and not just in border states but across the country.

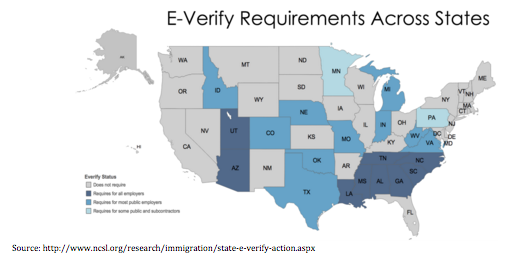

Most famously, Arizona passed the “Support Our Law Enforcement and Safe Neighborhoods Act,” Senate Bill 1070 in 2010. Among other things, the legislation requires law enforcement officials to check the immigration status of persons stopped or arrested for any reason such as speeding or other minor infractions. Though several states considered like bills that year and a number also passed similar legislation in 2011, including Indiana, Georgia and South Carolina, the Arizona bill gained the most attention as it was successively challenged in the courts. Upon reaching the Supreme Court, parts of the contentious bill were struck down but the most controversial element requiring police to inquire into the immigration status of detainees was upheld. While the Court did clarify that states cannot craft policies that undermine federal law, including ones criminalizing certain activities of undocumented immigrants such as seeking employment, the Governor of Arizona Jan Brewer declared it a victory for “the inherent right and responsibility of states to defend their citizens.” 2010 was not the first time Arizona blazed the trail on immigration enforcement legislation. The state also passed contentious bills challenged by the courts in both 2005 and 2007. The former made smuggling immigrants a state crime and the later required all employers to use E-verify.

E-Verify

E-verify is an online program that enables employers to check the work authorization of their employees. While the federal government established the E-verify program in 1997, it made state utilization of the service voluntary. Requirements to use the program first emerged in Georgia and Colorado in 2006. Both states made use of the program mandatory for state employees and contractors. In 2007, Arizona became the first state to require all employers to utilize E-verify. Since that time, a variety of requirements on employers to check immigration status gained momentum across the states, with the number of states passing such legislation peeking in 2011. Over 20 states now require some form of use of the E-verify program. While Tennessee limits the program to private employers with 6 or more employees, Georgia established penalties for local governments that fail to verify the work status of their employees, and South Carolina instituted a 24-hour hotline to report E-verify violations.

Secure Communities and Priority Enforcement

In addition to crafting their own policies to bolster enforcement of immigration laws, states have also lately rebuked federal policies designed to expand enforcement. The Secure Communities program initiated by President Bush, extended by the Obama Administration, and run by the US Immigration Customs and Enforcement Agency (ICE) has been a recent target of state legislators and Governors alike. The idea behind the program is to better link federal immigration officials with local law enforcement through automatic data sharing to better apprehend and deport immigrants in the country illegally. However, after deportations increased significantly under President Obama and stories of families torn apart flooded the media, communities and activist groups began to complain that the program went too far. Thus, while Arizona and Texas’ recent acts sought to strengthen or shore up federal efforts deemed lacking, states like California and Colorado have instead worked to mitigate what is viewed as federal overreach on immigration enforcement.

Specifically, three states have passed what has been dubbed the “Trust Act,” beginning with Colorado in 2013. The act limits the circumstances in which state and local law enforcement comply with ICE’s requests to detain persons suspected of breaking federal immigration laws for more than 48 hours. Connecticut legislators unanimously passed their own version of the Trust Act later that year as did California. These states are joined by nearly 300 local cities and municipalities including Miami, Baltimore, Philadelphia and Los Angeles that passed ordinances and executive orders promoting noncompliance with the contentious program. In fact, the first dissent came from Chicago in 2011, soon after ICE announced the program’s nationwide rollout. Still more have voiced public concerns about the program. Even then Governor of Massachusetts and personal friend of President Obama, Deval Patrick, initially objected to the program before eventually implementing it. In response to such state and local pushback, the Obama Administration refocused the program to prioritize deportation of those with criminal records first. According to the agency’s official website, “ICE prioritizes the removal of criminal aliens, those who pose a threat to public safety, and repeat immigration violators.” By November 2014, the Administration announced that it would end Secure Communities. In its place is now a similar program called the Priority Enforcement Program, which will continue to leverage fingerprint data sharing systems between local and federal law enforcement but limit excessive detentions by requiring ICE to identify to local officials that a detainee is likely deportable or has a removal order in order to hold them.

Fighting Federal Immigration Executive Orders

The recent overturn of the federal Secure Communities program signifies the growing influence of states and localities in an area of public policy once inconceivable as a state or local priority much less a state pressure point on federal counterparts. States and municipalities continue to push the envelope on federal jurisdiction over immigration-related policy, most recently as Texas Governor Greg Abbott leads a lawsuit along with 25 other states against President Obama over his 2014 Executive Action granting a legal reprieve from deportation to hundreds of thousands of undocumented immigrants. So far, the coalition has successfully won at least two court rulings blocking the President’s immigration order, which the administration is appealing. Just this month, the Texas Governor also filed a lawsuit against the Administration over plans to resettle Syrian refugees in the state.

Human Trafficking

While much of the recent efforts by states and localities to influence immigration enforcement policy stirred controversy, one component of recent state enforcement legislation has garnered broad-based and rising support: human trafficking. Immigrants and particularly undocumented migrants are some of the most vulnerable to labor as well as sex trafficking in the US because traffickers may effectively coerce victims through the threat of arrest and deportation, even in cases where the trafficked persons have the legal right to work. 37 out of 50 states passed legislation related to human trafficking in 2014 alone including bills to criminalize sex and labor trafficking, train law enforcement officers, and provide safe harbor and civil damages to victims. Between 2011 and 2014, the number of states granted the highest rating of “Tier 1” by the influential Polaris Project for their efforts to enact human trafficking legislation in 10 key categories nearly quadrupled from 11 to 39. Unlike recent border protection, apprehension, and deportation-related policies formed at the state and local levels, recent human trafficking legislation has focused on building local capacity and awareness rather than shoring up or circumventing existing federal law. Though major federal legislation on human trafficking passed in 2000, advocates have since pushed for matching state and local laws citing the vital importance of the law enforcement officials on the ground every day to identify, prevent, and protect against trafficking.

Integration:

Enforcement is not the only policy domain related to immigration that states delved into in recent years. States and municipalities have long played a vital role in the integration of immigrants and resettlement of refugees in the US. And these efforts have become more important than ever as immigrants from a wider array of sending countries settle in a greater diversity of states and localities across the US. Over 13 percent of the population is foreign-born in the United States today, compared to 11.5 percent in 2004 (BNAC report) and 7.9 percent in 1990. Many of these newcomers, moreover, are not settling in the traditional locations such as New York, Los Angeles and Miami but rather in places like Saint Paul, Minnesota, Boulder, Colorado, Seattle, Washington and Twin Falls, Idaho. The state of North Carolina has seen an increase of over 600 percent from 105,000 in 1990 to 651,000 in 2012.

Until just recently in the Fall of 2015, state and local action regards refugees and resettlement was less provocative and therefore infrequently reported on by the media. Nonetheless, states and localities have by and large taken creative steps to support the naturalization, civic engagement, community safety and economic vibrancy of these budding immigrant communities. While supporting integration, many of the new initiatives are also emerging as innovative strategies to meet local policy challenges from declining populations to unequal access to government services to lacking public safety. Not until the recent migrant crisis in Europe and the Obama Administration proposal to accept greater numbers of Syrian refugees was resettlement portrayed by the media and a number of state governors in such a negative light.

Troubleshooting Emerging Challenges

Hosting an influx of immigrants is not always an easy task. To confront related challenges from lack of awareness of public services to public safety, cities are adapting their policies and crafting special initiatives expressly targeting their burgeoning immigrant communities. In response to a high number of robberies reported against immigrant residents in Austin, Texas, for instance, the Police Department’s Office of Community Liaison created the Immigrant Outreach Program in 2001. Austin has since expanded efforts to increase communication with immigrant communities in the city. Immigrant communities across the US are often vulnerable to criminal activity due to the tendency of many immigrants to underreport crime. To combat this underreporting associated with distrust of law enforcement and fear of deportation, Austin opened a hotline for Hispanic immigrants to report crime in Spanish called “Tu Voz” and later created a cultural diversity panel made up of Asian immigrant residents to train all new police officers.

Resettlement

Though primarily organized through the federal government, states and localities are on the frontlines of refugee resettlement efforts in the US. Minnesota, for instance, is one of several states and cities that have made a concerted effort to host refugees through the federal government’s Refugee and Resettlement program. The state has over 100,000 refugees including from Somalia, Vietnam, Burma, and the former Soviet Union. To support these new arrivals, state and local government partners host a number of programs and events. Each year, with the support of funds from the Minnesota Legislature, for example, St. Paul and Minneapolis host the Twin Cities World Refugee Day to celebrate and recognize the cultural contributions of the state’s substantial refugee population.

Most recently, states have stepped up to respond to the unexpected influx of unaccompanied minors from Central America in 2013 to 2014. While media attention tapered as the surge in these child arrivals diminished, the impact of their arrival on government resources and communities is just being realized. From budget shortfalls to backlogs in licensing caregivers, states face significant consequences. In 2014 alone, Florida accepted nearly 5,500 unaccompanied minors while smaller states such as New Jersey and Virginia took in even more relative to their resources at over 2,500 and 4,000 respectively.

A number of other states and localities have risen to bear the brunt of the impact, creating programs and dedicating resources specifically to aid the minors. California, for instance, volunteered budget resources to provide legal representation to unaccompanied minors through nonprofit organizations. Through a public-private partnership, Maryland launched a website, BuscandoMaryland.com, for caregivers and children to find and connect with resources. At the same time, Texas increased its border protection budget by $1.3 million per week to stem the inflow of unaccompanied children into the country and the state.

With the most recent Obama Administration proposal to increase the country’s total refugee intake from an average of 70,000 annually to 85,000 in 2016 and 100,000 in 2017, new controversy related to overburdened local resources and especially security is surfacing in states and municipalities. Much of this contention is heightened by the anti-immigrant rhetoric of several current candidates for the US presidency as well as fear of accepting Muslim immigrants and others emerging from countries ravaged by terrorism. About half of US Governors voiced concern or stated blatantly that they will not accept this newest wave of refugees while at the same time a coalition of nearly as many Mayors from cities including Boston, Saint Louis, Dayton, and Los Angeles responded by requesting even more refugees. Whether this heated debate will result in policy action overturning years of largely supportive refugee programs at the state and local level is yet to be seen.

Promoting Naturalization, Citizenship and Civic Engagement

In addition to responding to problems by engaging their immigrant communities, many cities and states are partnering to promote citizenship, encourage civic engagement, and strengthen community life in advance of policy dilemmas arising. Alexandria, Virginia, for instance, hosts an Annual Citizenship Day to highlight the city’s openness including through a naturalization ceremony hosted in coordination with USCIS and opportunities to speak with city officials. Taking it a step further, Boston launched the New Bostonians Vote Campaign in partnership with over 150 local organizations to increase voter registration amongst immigrant communities in the city.

Beyond single-day events or short-term campaigns, some cities and localities are even imbedding immigrant civic engagement into their governance systems. To encourage immigrant civic involvement and input in city affairs, Boulder, Colorado created the Immigrant Advisory Committee in 2006. The committee of seven advises the city manager on how to better provide services—from housing to library opportunities—to the city’s growing immigrant population as well as incorporate immigrant residents’ perspective into city initiatives from transit planning to fire department programs to park development.

Finally, states and localities have begun to consider significant funding investments to promote citizenship and immigrants acquiring legal status. In June of 2015, California passed a budget including $15 million for education and outreach promoting citizenship as well as the federal DACA and Deferred Action for Parents of Americans (DAPA) programs. Together, these new approaches by states and municipalities across the country mark a turn toward a more proactive immigrant integration strategy for the 21st century.

Immigrants as A Development Strategy

In addition to smoothing integration and resettlement as well as soliciting immigrant input to enhance local governance and community life, states and localities are harnessing the potential of their burgeoning immigrant communities to solve intractable policy conundrums impacting all of their residents. Some, for example, are recruiting immigrants to restore economic vitality and cultural vibrancy in their communities. Baltimore is among several cities and states that has recognized immigration as an opportunity to tackle declining populations as well as public safety while bolstering economic development. The city is actively seeking to recruit immigrants and immigrant families including through an executive order issued by the Mayor stating immigrants using city services will not be questioned about their immigration status. Baltimore also hosts sensitivity training for city officials including law enforcement, and offers city-sponsored trainings in legal processes for new immigrants. As a top aide to the Mayor put it, “If we were able to say that we were no longer losing population? That’s something a mayor hasn’t been able to say since the ’40s.”

Other cities such as Detroit, Michigan and Dayton, Ohio have instigated initiatives to attract immigrants from providing assistance in starting small businesses to hosting an annual soccer tournament. An even more comprehensive approach specific to immigrant entrepreneurs was launched in New York City by then-Mayor Bloomberg in 2011. The first component of the strategy was the creation of a competition designed to reward organizations that developed innovative and scalable programs to support local immigrant entrepreneurs. The second program expanded the city’s business counseling services to include several additional languages common amongst New York small business owners and immigrants such as Chinese and Russian. Finally, the Mayor hosted an expo for local food manufacturers—an industry dominated by immigrants—to support these specialty businesses as the industry grows in New York. These programs required unprecedented coordination between the city’s Small Business Services, Economic Development and Immigrant Affairs offices.

Much of these efforts emerge from recent research highlighting the outsized benefits of immigrants to the US economy. One study, for instance, found that in 2011 over a quarter of new businesses in the US were started by immigrants and immigrants were twice as likely to start a business as their native-born counterparts. Unfortunately, few data sources consistently track immigrant contributions specifically as compared to the myriad sources tracking contributions and differences by race, for example. Though there is limited precise data on immigrant contributions to economic growth, 15 cities including the founding cities of New York, Chicago and Los Angeles, are also now part of “Cities for Citizenship,” a public-private partnership promoting economic development through leveraging current resources to increase naturalization.

One-Stop-Shop State & Local Resources

Finally, several states have created entire offices and departments to specially serve immigrants and immigrant communities. Louisville’s new Office of International Affairs (OIA), for instance, serves the city’s growing multicultural community with programs from a translator bank to diversity training to leadership opportunities. This and similar offices in municipalities across the states including Boston’s Office of New Bostonians and the Mayor’s Office of Immigrant Affairs (MOIA) in New York now serve as one-stop-shops for resources and referrals to everything from language courses to job training to social services.

Again, though sufficient research has yet to explicitly quantify the benefit of such initiatives, states and municipalities across the country are increasingly offering resources and services tailored to immigrants to meet their community’s’ growing needs as well as compete with other cities and states for new residents and economic growth.

Rights, Services, and Access to Benefits

Over the last two decades, states actively passed laws that expanded or restricted the access of immigrant communities to state-sponsored rights, services, and benefits. While much of this legislation is persistently controversial, including immigrants’ access to healthcare benefits, other bills enjoy increasing bipartisan support, such as measures supporting in-state tuition for undocumented children. Since the most recent failure in 2013 of a federal immigration overhaul bill, in particular, several issues related to the rights and benefits of immigrants gained attention and increased action at the state level. Amongst those, granting eligibility for driver’s licenses generated some of the most heated debate. While federal immigration reform dithers, these state decisions are significantly impacting the everyday lives of hundreds of thousands of immigrants and their families. Whether circumventing federal action, augmenting it or explicitly combating federal law, state entrepreneurship related to immigrant rights, services, and access to benefits continues, testing the equation of state-federal power over immigration policy.

In State Tuition

Perhaps the most well-known debate related to immigration today is the battle over access to in-state tuition rates for undocumented immigrant youth. From red states to blue states and large states to small states, the issue is getting traction in state legislatures and institutions of higher education.

20 states, home to the majority of undocumented immigrants in the country, now offer in-state tuition rates at state-sponsored schools to undocumented immigrant children. Texas instigated the trend back in 2001 with Colorado, New Jersey, Oregon, and Minnesota passing legislation most recently in 2013. Typically, these laws specify the qualifications for in-state tuition and most often those requirements include the following:

- Attended high school for a certain number of years in the state (typically two or three).

- Graduated from high school in the state; and

- Sign an affidavit stating the intent to apply for citizenship.

The jump in state legislation in 2013—after a decade of no more than one state passing a similar bill in any one year—coincided with the failure of Congress to pass the DREAM Act at the federal level. In the most recent hopeful attempt, the Senate passed an in-state tuition bill in 2013 but the House did not follow suit.

While most Americans are aware of the DREAM Act, many do not know the controversy regarding in-state tuition has a longer history than recent years suggest, beginning with the US Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) of 1996. Current efforts to pass a DREAM Act at the federal level do not clarify the qualifications for in-state tuition to ensure undocumented children may be eligible as recent state bills have. Rather, Congress is simply still debating whether to dismantle its earlier work designed precisely to prevent states from granting such access. Though intended primarily to strengthen immigration enforcement and border protection, the broad sweeping IIRIRA bill also inhibited states from providing such benefits as in-state tuition by explicitly restricting state use of residency as a prerequisite for such a benefit. State bills after 1996, therefore, were made necessary to overcome the federal barrier and allow undocumented immigrant children to attend state universities at the rates of other state residents. They circumvent those barriers by basing students’ claims not on residency but alternate requirements (listed above).

Though President Barack Obama issued an executive order in 2012—the famous Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA)—which has opened up greater access to in-state tuition for formerly undocumented child migrants in some cases, several states and advocates within them continued to push for a more permanent solution through state law. To date, states including California and Illinois have even gone as far as authorizing private scholarships for immigrant children to attend state schools. At the same time, not all states have favored greater access to higher education for immigrant youth. Six states passed laws explicitly banning undocumented immigrant children from receiving in-state tuition. With only five of those bills still in effect and no new such laws since 2011, however, the momentum is behind increased access.

Access to Health care Benefits

Though the debate over in-state tuition is likely the best-known controversy involving immigrant rights, benefits, and access to services as of late, states have also been center stage in the debate over public benefits access for immigrants and their families.

Health care access, particularly since the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and the related regulations explicitly barring immigrants from accessing it, has emerged as another hot topic on state and local agendas. According to an estimate by researchers at UCLA, over 5 million undocumented immigrants will lack health insurance by 2016, causing concern for many states and especially those with large immigrant populations. As written, undocumented immigrants do not have access to healthcare benefits and tax credits provided through the Affordable Care Act (ACA) or other federal programs. Meanwhile, legal immigrants may access federal health care benefits only after five years of residence in the US. With these time restrictions and other prohibitions to accessing federal-level benefits, multiple states have experimented with their own health benefit policies to provide immigrants access to affordable insurance and, therefore, preventative and early care. Motivating these states is largely the desire to contain costs by channeling immigrants away from incredibly expensive emergency rooms visits.

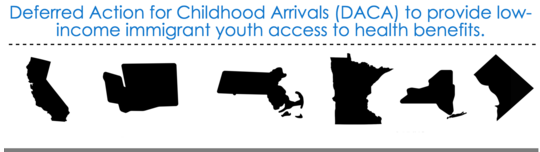

Five states and the District of Columbia have, for instance, found creative ways to use President Obama’s 2012 executive order relative to Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) to provide low-income immigrant youth access to health benefits. By using only the federally granted legal documentation but not federal dollars, California, for example, incorporated the newly documented youth into Medi-Cal. In the state’s most recent budget deal, in fact, Medi-Cal is set to be expanded to include all undocumented children under the age of 19 by May 2016. In 2014, Los Angeles County even created a program, My Health LA, to allow all undocumented immigrants access to free healthcare, designating $61 million to the initiative establishing local clinics as home-bases for undocumented and uninsured immigrants to receive health care.

Other states and localities provide access to state-sponsored health benefits for particular subsets of immigrants. Whereas Alaska covers certain immigrants with chronic and terminable diseases, Illinois offers coverage to victims of abuse, and Massachusetts provides limited services for seniors and those with disabilities. Finally, many states take advantage of the federally funded option to allow pregnant women and infants access to subsidized health care.

With the momentum to include immigrants in state health benefit options only just budding in the wake of explicit prohibitions in the ACA and DACA, there is not yet a body of evidence to validate the cost-savings of these measures. Nonetheless, advocates maintain that the plethora of research related to savings from preventative care and emergency room avoidance indicate savings will be substantial. Until such data is available, it is yet to be seen if other states will follow the lead of California, New York, and their fellow progressive counterparts in providing immigrants access to subsidized health care.

Cash, Food, and Other Benefits

Health care for low-income residents is not the only form of benefit undergoing policy reform at the state and local level. Like health care benefits, federal action or inaction has often been the spur for states to expand or limit cash and other in-kind benefits for immigrants.

Since the passage in 1996 of federal Welfare Reform, or the Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Reconciliation Act (PRWORA), the majority of states have taken matters into their own hands to deliver tailored benefits opportunities to documented and undocumented immigrant residents. That law limited most federal benefits to immigrant citizens, refugees, and immigrants lawfully in the country for five or more years. Since PRWORA, according to the Pew Charitable Trusts, 40 states in total have either implemented state-only funded programs to expand access to immigrants not qualified for federal benefits or opted into more recent federal opportunities to expand state-matching coverage to pregnant women and infants.

The public benefit most commonly extended to immigrants in states across the US today is actually cash assistance for low-income families mirroring the federal Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program. 23 states, or nearly half, provide such a program funded entirely by their own coffers. Only five states meanwhile provide food assistance programs specific to immigrants. They include California, Connecticut, Maine, Minnesota and Washington State.

Though many states have worked to fill the place of federal programs for low-income immigrant families, it should be noted many do not provide benefits at the same rate as provided through federal programs. Several of the states that offer food assistance, for example, offer just 75 percent of the federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefit.

Since the enactment of PRWORA, the results of differential access to benefits across the states have been better documented than many reforms impacting immigrants. Food insecurity in the 23 states offering the least amount of assistance to immigrants after Welfare Reform, for instance, rose by roughly five percent amongst immigrants while simultaneously dropping for native families, according to the Migration Policy Institute. Unsurprisingly, immigrants’ use of all categories of benefits also dropped significantly after the enactment of PRWORA.

The Driver’s License Debate

A final debate states are grappling with relative to immigrants’ access to rights, benefits, and services available to other US residents recently sprung up over driver’s licenses. By the end of 2014, 10 states offered driver’s licenses to unauthorized immigrants. That number jumped to 12 by July 2015.

The issue gained traction beginning in 2013 when at least seven states enacted legislation expanding access to driving privileges for immigrants in that year alone. In total, 25 states considered legislation regarding driver’s licenses for undocumented immigrants in 2013. The contest continued this year with heated debates raging in states from New Jersey to Georgia to North Carolina.

Municipalities have also jumped into the fray, offering their own versions of identification cards to immigrants in lieu of driver’s licenses (which states but not municipalities have the right to grant). Cities such as Princeton, New Jersey and New Haven, Connecticut introduced community ID cards which immigrants could present to law enforcement as well as use to access public schools, libraries, and parks. The state of Connecticut since passed its driver’s license law in 2013.

Utah was the first state in 2010 to create a special class of driver’s license for immigrants. Since then, however, the state has faced scrutiny as at least one immigrant granted a license was found to have multiple convictions for drug dealing and violent crime after providing false identification. The state now requires fingerprinting in order for immigrants to access driver’s licenses.

Finally, two states, Nebraska and Arizona, passed bills to explicitly deny the access of DACA recipients to driver’s licenses. Neither law remains in effect as Arizona’s was overturned in court and Nebraska’s state legislature overturned the Governor’s veto on a bill granting undocumented youth with DACA papers driving privileges on May 28, 2015. To date, approximately 37 percent of unauthorized immigrants live in a state in which they can access a driver’s license.

With these recent wins, the issue surrounding driver’s licenses for unauthorized immigrants is only just beginning to heat up and the debate at the state level promises to continue to rage into 2016.

Conclusion:

Immigration and immigrant integration is a policy arena in which the balancing act between the state and federal governments is truly exposed. Though not widely considered a state or local issue, immigration and policies impacting immigrants have topped agendas and inspired strong debate in state legislatures and even in city halls across the country.

While federal immigration reform dithers, states have stepped into the breach to meet emerging challenges and serve their shifting demographics in the 21st century. At the same time, much of the efforts at the state level have come in reaction to major federal action from PRWORA to the ACA to DACA. Regardless of the reason, it is clear that we are witnessing an era of entrepreneurial policy reform related to immigration at the state and local level. With several issues only gaining traction at the state level as recently as 2013, the debate is poised to continue for the foreseeable future.

In recent years, immigration-related policy has increasingly highlighted the dynamic relationship between our levels of government. State and local policy entrepreneurs have pushed the boundaries on what was formerly deemed a policy arena squarely within the federal domain. As we move firmly into the 21st century, immigration policy will continue to showcase how states and localities are playing a major and increasing part in a bevy of policy issues greatly impacting US residents.

Stephanie Keller Hudiburg is a recent graduate of the McCourt School where she focused on community and economic development policy, public sector innovation, and performance management as the Co-Director of the McCourt School Policy Innovation Lab and a Research Fellow with the Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership. Before moving to DC, Stephanie served as the Chief of Staff to a State Senator representing Boston in the Massachusetts Legislature. She is now the Director of Programs and Partnerships at The Real Estate Council in Dallas. Stephanie is a state and local policy enthusiast, writing on several related innovations and reforms for this series.

I can see you registered http://gppreview.com/2015/12/09/states-take-on-immigration-policy-not-new-but-a-growing-trend/ for a decent

period, is that for search engine optimisation?

p.s Don’t take advice from the Warrior Forums haha