Events over the past few months including the rising popularity of nontraditional, anti-establishment presidential candidates, an insurgency within the House of Representatives leading to the early retirement of John Boehner, and a politically detrimental showdown with Hillary Clinton over Benghazi, have the Republican establishment visibly shaken. On the congressional front, party Golden Boy, Paul Ryan, probably sacrificed his future dreams of the Oval Office to take over the party’s highest leadership position. A move that may not be good for the party long-term, but salvaged what could be saved of the party’s leadership. Further complicating its image problem is the free for all nomination race that has all but ostracized the first establishment favorite, Jeb Bush, and failed to check the momentum of its unconventional candidates, who now account for over fifty percent of popularity in national polls but whose cumulative governing experience equals…zero.

Amidst the circus noise one thing is clear: what is at stake in this election is whether the Republican Party can prove they have what it takes to govern the country. If this is their chance to elevate above the fragmented picture of the last few months (or years) of being “anti-everything” to an actual platform, then the establishment should put its bets on the table now and push its chips towards Marco Rubio.

Conventional wisdom, history, and the structure of the modern Primary system points to the important influence of the party establishment in the selection of the nominee. A group of political scientists published this theory by its name in a 2008 book. The Party Decides asserts that party insiders – officeholders, governors, state party leaders, and activists – have considerable influence to pick a frontrunner before voters have any meaningful impact in the process. A number of sources suggest endorsements, particularly early ones, are more predictive of the future nominee over both fundraising and polling. Further evidence of this comes from fivethirtyeight’s political endorsement tracker, which shows unprecedented low levels of endorsements and political commitments at this point in the race.

But the growing concern is about establishment backlash: that John Boehner’s resignation and the popularity of leading contender Donald Trump’s demeanor and provocation is a sign of the rising “angry American voter” visibly undermining the party’s power. The most recent races in 2008 and 2012 give credence to critics of the “Party Decides” theory that the influence of the party establishment to determine the nominee is waning or ambiguous at best. In these cases, one looks at how the party acts given there is no clear heir apparent, like a Vice President or other party favorite. Given these circumstances, the party’s indecisiveness prolongs and results in the party following the voters, not the other way around.

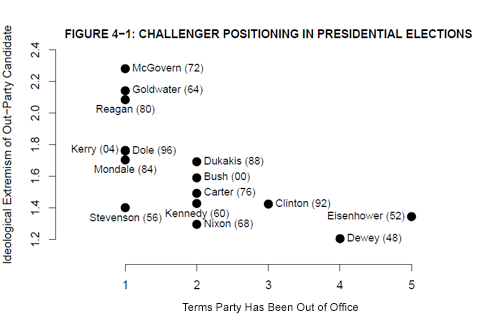

Many insist that polls this far out have very little relationship to the final outcome. It seems there is no conclusive evidence at present that either viewpoint will hold, but that does not mean there is no advantage to the Republicans backing an establishment candidate like Rubio. The party, even though modern presidential races provide a small sample size, still has history on its side. The longer a party is out of the White House, the more likely it is to emerge from the nomination process with a moderate candidate. The figure below demonstrates how candidates in an election where the opposition is two or more terms out of the White House move closer to the ideological center (see Clinton ’92, Dewey ’48).

If Rubio pulls off another strong debate performance, the establishment should fortify behind him because the cost of not doing so could be too high. The Electoral College makes winning the White House a game of margins. Looking back at elections from 1860 onwards; the eleven times (or twelve depending on how you count Grant) when an incumbent president stepped aside (before the 22nd Amendment) or was forced out by term limits resulted in, “four clear wins for the incumbent party, three clear losses, and four elections that were very close.” On average, the incumbent party won the Electoral College by a margin of error of 3.8 percent. In contrast, when the incumbent party has only served one term, and the opponent must face a sitting president, the opposition party faces a much steeper obstacle: the incumbent party has won the popular vote in 14 of 18 elections and the Electoral College 13 of 18 times (Analysis taken from Nate Silver from fivethirtyeight).

In 2012, President Obama won the popular vote by 2.5 percentage points, but reached the minimum votes to secure the Electoral College fairly early in the night sealing re-election. In Ohio, he won the popular vote by only 1.9 percentage points and in Florida by 0.6 percentage points. He won Colorado more decidedly, by almost 5 percentage points. Looking at these numbers, in the context of a young Cuban-American Senator from Florida, and a popular moderate, budget-balancing governor from Ohio as a potential running mate, makes it seem as if the Republican ticket could have the power to shift these electoral votes back to red. But even if Obama lost Ohio and Florida in 2012, he still would have won the election when Colorado put him to 272, and Virginia to 285. But Colorado is far from certain for Democrats. Dems narrowly lost this key Senate race in 2014 which helped swing the pendulum to a Republican majority in the Senate. And, who did Senator Cory Gardner, the guy who unseated the Democratic incumbent in 2014, just endorse? That would be Marco Rubio.

While it makes a Rubio-Kasich ticket compelling, none of this provides Republicans with more certainty in the present. It is entirely possible that Hilary Clinton’s Electoral College setup looks much different and plays to different strengths and weaknesses than Obama’s, further confounding any predicted leanings or advantages. Some of us are not old enough to remember, but California at one period in time from 1968 to 1988 voted Republican in every presidential election.

There are a number of alternative realities that pundits will certainly continue to propose as Iowa and New Hampshire grow near. Why would the Republican establishment want to wait for any of these to unfold as truth, when a number of them are ill-fated for their ends? Achieving internal order is certainly not a requirement to win the White House, nor proof of their governing competence, as evidenced by the Democrats in 2008. But it would go a long way to signal to voters in the general election that Republicans can be decisive and practical, and contend on a unifying, rather than factional, platform.

Erin Mullally is a second year MPP student at the McCourt School of Public Public Policy at Georgetown University, and Editor-in-Chief of the Georgetown Public Policy Review. Prior, she spent three years working for the City of Kansas City, Missouri, serving as a communications and public affairs aide to Mayor Sylvester "Sly" James, Jr.

Because of state winner-take-all laws for awarding electoral votes, analysts concluded months ago that only the 2016 party winner of Florida, Ohio, Virginia, Nevada, Colorado, Iowa and New Hampshire (with 86 electoral votes among them) is not a foregone conclusion.

Only 10 states were considered competitive in the 2012 election. More than 99% of presidential campaign attention (ad spending and visits) was invested in them.

So, if the National Popular Vote bill is not in effect, less than a handful of states will continue to dominate and determine the presidential general election.

Over the last few decades, presidential election outcomes within the majority of states have become more and more predictable.

From 1992- 2012

13 states (with 102 electoral votes) voted Republican every time

19 states (with 242) voted Democratic every time

If this 20 year pattern continues, and the National Popular Vote bill does not go into effect,

Democrats only would need a mere 28 electoral votes from other states.

If Republicans lose Florida (29), they would lose.

Population shifts have converted states that were once solidly Republican into closely divided “battleground” states.

There do not appear to be any Democratic states making the transition to voting Republican in presidential races.

In the 2015 elections, “in blue states and cities, the [Democratic] party held or gained ground. As the parties head into a new presidential year, the country’s partisan divide has deepened. Republicans walked away from Tuesday with the big wins. Democrats walked away with fresh confidence that their map can win a third presidential election in a row.” . . . “the [Democratic] status quo continued. The blueness is seeping out from the cities as folks move and settle families. It’s a long-term shift.” – Washington Post, Off-year elections reveal a 2016 map with sharper borders, Nov. 4, 2015

Some states have not been competitive for more than a half-century and most states now have a degree of partisan imbalance that makes them highly unlikely to be in a swing state position.

• 41 States Won by Same Party, 2000-2012

• 32 States Won by Same Party, 1992-2012

• 13 States Won Only by Republican Party, 1980-2012

• 19 States Won Only by Democratic Party, 1992-2012

• 7 Democratic States Not Swing State since 1988

• 16 GOP States Not Swing State since 1988

In the 2012 presidential election, 1.3 million votes decided the winner in the ten states with the closest margins of victory.

Issues of importance to non-battleground states are of so little interest to presidential candidates that they don’t even bother to poll them.

Over 87% of both Romney and Obama campaign offices were in just the 12 swing states. The few campaign offices in the 38 remaining states were for fund-raising, volunteer phone calls, and arranging travel to battleground states.

Since World War II, a shift of a few thousand votes in one or two states would have elected the second-place candidate in 4 of the 15 presidential elections

Policies important to the citizens of non-battleground states are not as highly prioritized as policies important to ‘battleground’ states when it comes to governing.

“Battleground” states receive 7% more federal grants than “spectator” states, twice as many presidential disaster declarations, more Superfund enforcement exemptions, and more No Child Left Behind law exemptions.

Presidential elections don’t have to continue to be dominated by and determined by a handful of swing states.

The National Popular Vote bill would guarantee the presidency to the candidate who receives the most popular votes in the country.

Every vote, everywhere, would be politically relevant and equal in presidential elections. No more distorting and divisive red and blue state maps of easily pre-determined outcomes. There would no longer be a handful of ‘battleground’ states where voters and policies are more important than those of the voters in 80% of the states that now are just ‘spectators’ and ignored after the conventions.

The bill would take effect when enacted by states with a majority of Electoral College votes—that is, enough to elect a President (270 of 538). The candidate receiving the most popular votes from all 50 states (and DC) would get all the 270+ electoral votes of the enacting states.

The bill has passed 33 state legislative chambers in 22 rural, small, medium, large, red, blue, and purple states with 250 electoral votes. The bill has been enacted by 11 jurisdictions with 165 electoral votes – 61% of the 270 necessary to go into effect.

NationalPopularVote.com