For the full report with citations, the PDF can be downloaded here.

Introduction

Until recently, what we did with the incarcerated was not the sexiest topic in US policy and politics. Most politicians know preaching about the ills of our prison systems is not likely to get out the vote while the danger of appearing soft on crime is always salient. Within the constraints of these political realities, criminal justice reform was mainly the domain of a few progressive advocacy groups, lawyers, and a handful of leaders representing the socio-economically disadvantaged and racial minorities often most impacted by the criminal justice system. Despite long-standing efforts of these few to reform what is now widely considered a broken system, little significant or comprehensive change occurred within this policy realm since the War on Crime and War on Drugs era of the late 1960s and early ‘70s. That is, until the recent economic recession.

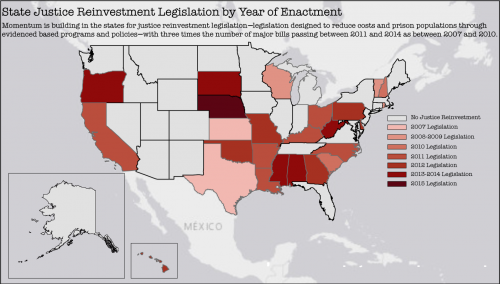

Beginning in 2007—and picking up steam since 2010—states embarked upon major efforts to reform their criminal justice systems. What sparked the recent flurry of activity, interestingly, was not the widespread recognition of years of ineffective policy in need of change, but the fiscal strain for many states of their swelling prison costs. Between 1990 and 2010, corrections expenditures grew by 400 percent, with only Medicaid outpacing their growth in state budgets. According to former Oklahoma House Speaker Kris Steele, “The cost of doing nothing was too much.” Squeezed by shrinking state coffers and emboldened by the success of some early leaders including Texas, more than 28 states embarked on what is now commonly known as “justice reinvestment” since 2007.

Simply put, this justice reinvestment movement applies the principals of cost-efficiency and evidenced-based programming to sentencing and corrections policy. It is an effort by states to introduce multiple and significant, if not always comprehensive, reforms to their criminal justice systems based upon evidence of what works in decreasing incarceration rates, containing costs, and reducing recidivism. Many states formed commissions and task forces to review their current criminal justice systems and make recommendations to stop or reverse the long-trending growth in corrections expenditures, while reducing recidivism and maintaining public safety. Already, several states netted savings in the millions with hundreds of millions more projected over the next five to 10 years. Several closed prisons for the first time in decades. Though the available data and research to date are not yet conclusive, the tide of justice reinvestment is bringing much needed optimism to a long troubled policy arena.

The War on Drugs: The Seventies through 2007

The Impact of Historic US Criminal Justice Policies

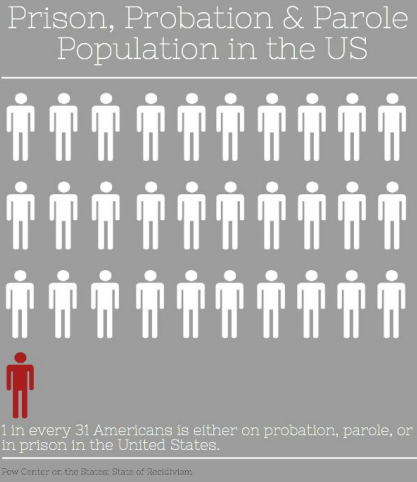

In large part, justice reinvestment is emerging as an antidote or response to the flurry of criminal justice policy and laws put in place over four decades ago, during the early 1970s. With crime on the rise, elected officials led by Richard Nixon sought to stem the tide through enacting tough measures to deter would-be criminals and sternly punish perpetrators. States followed suit, implementing their own series of retributive laws. The intended and often unintended consequences of these policies shaped the modern American criminal justice system, with the US housing 25 percent of the world’s prison population, despite claiming only 5 percent of the world’s total population.

Incarceration Explosion & Its Consequences

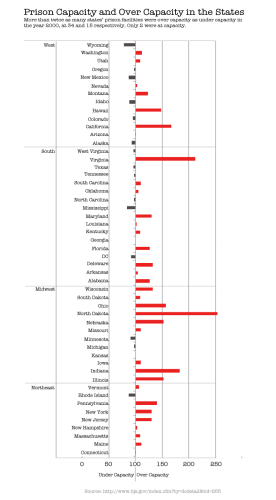

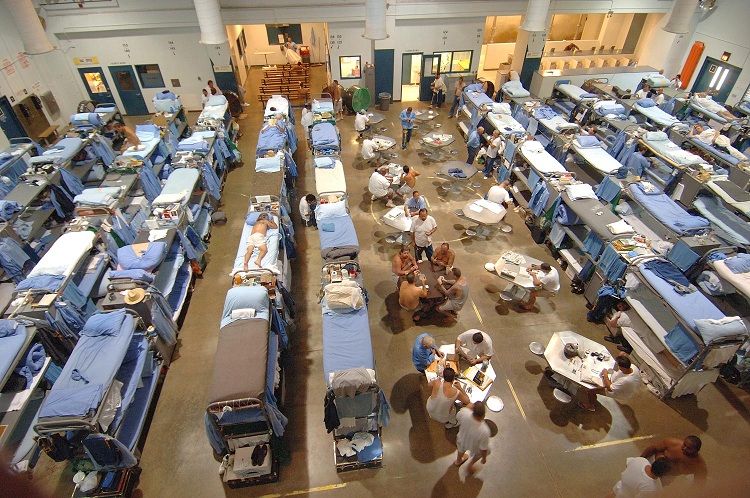

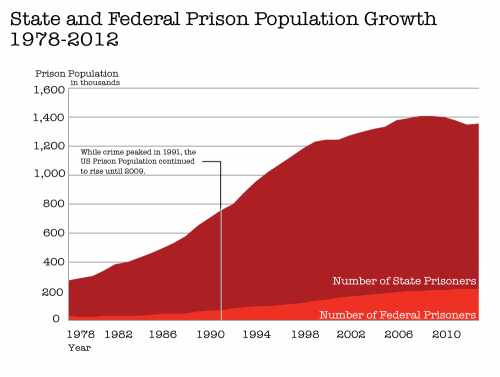

Prison development exploded over the next decades, with a 700 percent increase in the incarcerated population since the 1970s costing taxpayers $39 billion in 40 states. To accommodate these inmates, correctional facilities grew by over 50 percent between 1990 and 2005 alone. Interestingly, the majority of prison growth was driven not by Nixon’s federal policy push but by state policies, beginning roughly in 1975. State corrections spending has nearly quadrupled since the early 1990s.

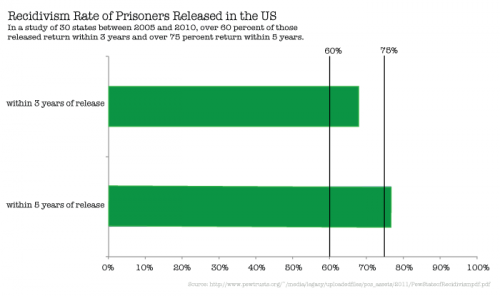

In addition to the obvious monetary costs associated with this expansion, serious social consequences have reverberated, particularly through poor and minority communities as institutional disparities in the severity of sentences and related personal and family hardships became engrained. Barred from voting and many forms of employment and with little support post-release, many Americans came to find prison a way of life. According to a Pew Research Center longitudinal study, nearly half of all released inmates in the US return within 3 years.

Crime Rates and Drugs

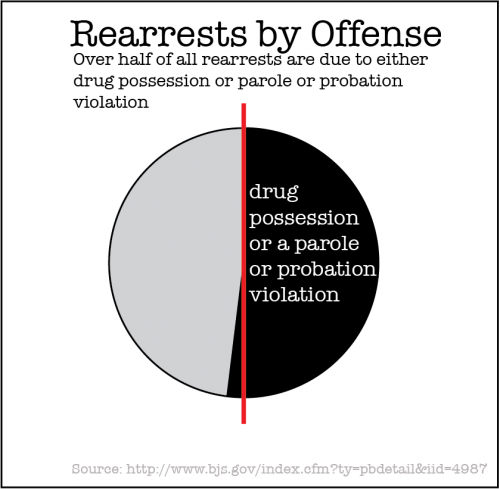

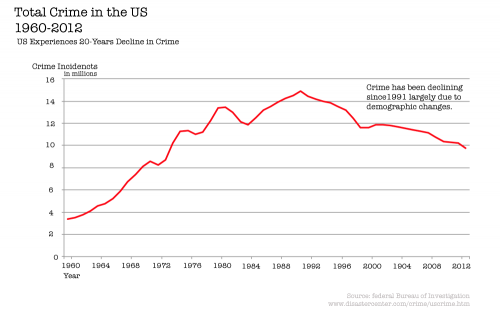

Despite the significant shift in policy in the 1970s and associated growth in incarceration across the US, the War on Crime and related War on Drugs did not work. In fact, after Nixon’s policy move and subsequent state law changes, crime rates actually rose dramatically between the 1970s until the early 1990s. While many attribute this increase to population changes and simple demographics, namely the decline in the youth population, drug-related crimes also contributed to the increase. Drug crimes in particular exploded throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, from 41,100 in 1980 to 493,800 in 2003, or over 1,000 percent. Drug abuse violations continue to top the list of arrest offenses today. Nearly 50 percent of federal inmates in 2014 were serving time for drugs, while the next largest category of offenders were immigrants at 10.2 percent, followed by 6.7 percent for sex offenses. Moreover, according to a recent Bureau of Justice Statistics study, over 50 percent of rearrests of prisoners released in 2005 resulted from technical parole violations or drug possession alone as opposed to violent crime, theft, or any of the other categories of criminal activity.

Today: The Disparity Between Crime and Prison Population Rates

Today: The Disparity Between Crime and Prison Population Rates

Forty years later, crime, sentencing, and incarceration in the US are still shaped by the War on Drugs and War on Crime. Though the crime rate began to dissipate in the 1990s, prison expenditures, incarceration rates, and recidivism all remained high. Expenditures continue to rise and recidivism remains a significant problem with an average of 1 in 4 prisoners rearrested after release. As an Urban Institute study concludes, “despite the fact that correctional spending has increased from approximately $9 billion to $60 billion during the past 20 years, prisoners are less prepared for reentry than in the past.”

Today, then, we continue with a broken system that not only failed to accomplish its main goal but exacerbated crime rates in certain offense categories including many drug-related offenses in addition to escalating the cost of corrections dramatically.

Justice Reinvestment

To reverse the years of ineffectual criminal justice policies, escalating corrections expenditures and incarceration rates, states are employing a broad range of reforms. These changes impact the criminal justice system from the time defendants first appear in court through their stay in the prison system and after their release.

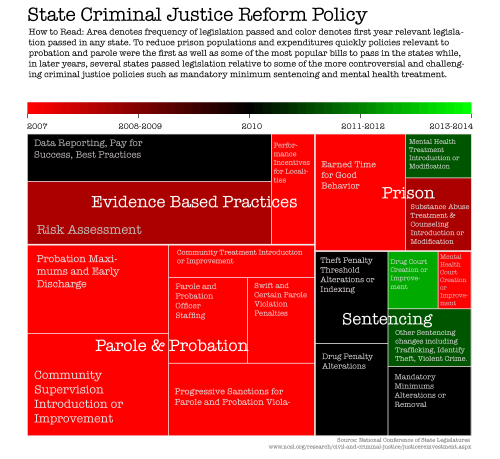

Sentencing

Studies indicate that serving time in prison and length of time served are some of the biggest predictors of recidivism. Repeat offenders comprise a high proportion of defendants in US courtrooms. Over 75 percent of felony defendants in the 75 biggest counties had at least one prior arrest in 2006, with 49 percent having multiple prior convictions and 35 percent having 10 or more past arrests. As such, much of the justice reinvestment effort across the United States focuses on preventing offenders from ever setting foot inside a prison. At least 13 out of 50 states made changes to their offense classifications and related penalties including the often-contentious mandatory minimum sentences.

Drug-related offenses in particular were reviewed and recommendations were adopted to raise thresholds and redirect users to services as compared to prison. Several states, such as Louisiana and Ohio, removed mandatory minimums for first-time drug offenders or in the case of plea deals, while others including South Carolina made voluntary enhanced penalties for two and three-strike offenders. In one creative approach, Pennsylvania repurposed mandatory minimum sentences to refer offenders to motivation boot camp or recidivism reduction training.

Some states also adjusted policies that disproportionately impact certain types of communities more than others. For example, several have adjusted school zone proximity triggers in cities, acknowledging the greater density of urban areas as compared to rural ones. While some such as Arkansas simply raised thresholds for theft and drug felonies, others including South Dakota relied on creating gradations or degrees of crimes to better distinguish appropriate sentences for crimes ranging from identity theft to trafficking. States are also taking steps to ensure sentences are administered by tailored courts with particular standards. Georgia passed legislation in 2012 to create drug and mental health courts while Oregon passed measures to established evidenced-based standards for specialty courts. Similarly, South Dakota established an advisory council to oversee and evaluate programs of drug courts. Together, these efforts to more finely discern appropriate sentences, divert defendants to treatment and services, and minimize prison time to only what is necessary are intended to contain the explosive growth and costs of US prison systems.

Inside Prison

While states are working to change their sentencing and intake systems, they are also implementing new policies to better support, treat, retrain and prepare inmates for reentry while they are in prison. Six states adopted measures including new or bolstered substance abuse treatment, mental health services, and educational opportunities for inmates while they serve their time. At least six states implemented drug screening and rehabilitation planning programs, including newly required assessments and treatment plans upon intake for all prisoners in Vermont and West Virginia. These states also mandated better distribution of corrections departments’ resources based on such assessments. For instance, Vermont converted one prison into a secure treatment facility. Performance incentives, typically referred to as “earned time for good behavior,” are employed to encourage participation in these programs and other preparations for reentry. Over 10 states including Kansas, Oregon, and Texas altered their laws to prioritize such opportunities to earn time. Some, including Ohio, even require what is known as “risk reduction” or “recidivism reduction” programming for non-violent sex offenders. And Wisconsin adopted a new law to implement risk reduction sentences, a new and distinct category of inmates eligible for release after program completion.

Post Release

In addition to sentencing and in-prison strategies, states are re-envisioning post-release policies and practices as part of their justice reinvestment efforts. To begin with, risk assessment and earned time are not reserved solely for in-prison time. Nine or more states including Kentucky, New Hampshire, and Louisiana implemented risk assessment requirements for parolees and probationers. These assessments may be used to determine the level of supervision a parolee or probationer will receive. In several cases including in Pennsylvania and Ohio they are also used to create individualized reentry plans for returned citizens. Risk assessment is, in fact, the most common policy area states have amended as part of their justice reinvestment plans, followed closely by community supervision.

Over half made community supervision a component of their reforms with some states including West Virginia and South Carolina mandating such supervision for most parolees. Other popular policy changes have included allocating new grants to localities to administer community supervision and establishing new community correction centers to house former inmates in the community. Pennsylvania and Ohio, once again, are taking the lead in these areas.

On the whole, the purpose of these community supervision policies is either to reduce sentences by allowing prisoners to serve their remaining time in the community, reduce re-offense and recidivism rates, or both. In 2013, Oregon passed a law creating a grant program to reward communities which reduce recidivism while states like Louisiana specifically offer workforce development training as an alternative to incarceration and path to improved outcomes.

Other key strategies states are using to reduce prison times and recidivism include adjustments to their parole and probation systems designed to better tailor punishments to the severity of violation and support reintegration of returned citizens into community life. According to a 2014 Bureau of Justice Statistics report, parole and probation violations constituted over a quarter of re-arrests before 2010 after an initial arrest in 2005. With simply failing to meet parole or probation requirements comprising such a high proportion of recidivism rates, nineteen states instigated policies ranging from probation limits to shock incarceration to progressive sanctions to combat such unnecessary burden on the system. For instance, to reduce the time returned citizens are on parole or probation, states such as Louisiana drafted rules providing for early release or limiting the length of probation for certain classes of felons and drug offenders as well. Kentucky has wholly eliminated or “discharged” probation for low-risk cases. States like South Dakota also implemented earned discharge, similar to earned time for good behaviour, for compliant probationers and parolees.

Other states incorporated graduated punishment schemes and other creative solutions to keep former inmates from simply going back to prison. In 2011, Arkansas passed a law allowing electronic tracking while states like Vermont permit home confinement as an alternative. States including New Hampshire and Oklahoma designated separate intermediate holding facilities solely for those whose parole or probation is revoked as compared to those arrested for other causes. These distinct facilities are intended to keep parole and probation violators out of prisons where they may renew bad habits, lose motivation more readily, or be negatively influenced by other inmates. Some of the most popular tactics employed by states are to allow administrative and graduated sanctions for certain technical or low-level violations. For instance, a violator may be required to complete residential treatment or community service. Such strategies, proponents believe, are more likely to set returned citizens on a right path than simply re-locking them up which may cause more harm than good.

The greater flexibility allowed by such graduated sanctions is mirrored in several states by greater flexibility granted directly to parole and probation officers to determine appropriate punishments based on the individual cases. While some states such as North Carolina allow probation officers to determine appropriate sanctions, others have crafted sanction grids or guidelines that enumerate specific sanctions to fit precise violations in particular types of cases. Such sanctions grids enable probation and parole officers to deliver “swift and certain” action other than immediate revocation to prison. In other words, these new tools allow officers to avoid lengthy court hearings in order to determine sanctions while also providing alternatives to simply sending violators back to prison.

Themes

As part of their justice reinvestment efforts, states across the US are adopting a variety of new and creative strategies to more appropriately punish and better rehabilitate prisoners whether prior to incarceration, while in prison, or once released. Taken together, the driving ethos behind these new schemes is a commitment to data-driven decision-making and evidence-based practices enabling more sophisticated and tailored actions. These tailored measures, in turn, are geared toward achieving the best outcomes and containing costs. Not surprisingly then, as a final part of their justice reinvestment packages, many states are enforcing new data reporting and performance measurement policies. Some states like South Dakota made funding for certain justice reinvestment programs, including drug treatment, contingent on evidence of success. Others require fiscal impact statements or the adoption of cost-benefit tools by their corrections departments to identify strategies, which reduce per-inmate expenses. On the whole, states are betting on these new evidence-based strategies to reduce costs, recidivism, and the incarceration rate all while continuing to combat crime and keep American communities safe.

Federal Role and Response

With state efforts in justice reinvestment gaining momentum and producing promising success stories, federal partners are taking notice. Soon after the first states piloted justice reinvestment initiatives, both the legislative and executive branch of the federal government began efforts to fund, market good practices in, and measure justice reinvestment efforts.

As early as 2008, members of Congress passed the Second Chance Act (Public Law 110-199). The legislation was the first to authorize federal grants, through the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA), to support programs designed to improve outcomes of the formerly incarcerated and reduce recidivism. The law includes funding opportunities for career training such as in technology, substance abuse treatment, evidenced-based community supervision, mentoring, and other transitional services. In 2012, the BJA initiated priority consideration for grant applicants with pay for success models. Like their state counterparts, federal regulators and legislators are focused on promoting what works.

Within the executive branch, the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, a public private partnership between the BJA and the Pew Charitable Trusts, was launched in 2010. The program is designed to provide technical assistance to states committed to implementing justice reinvestment. It was awarded funding in 2010 by Congress “in recognition of earlier successes of justice reinvestment efforts.” This Justice Reinvestment Initiative quadrupled in 2014, thanks to bipartisan support in Congress and an increased recognition across states of the multiple benefits of reform. In 2014, support for criminal justice reform and reinvestment continued to grow and evolve as Senators Cory Booker (NJ – D) and Rand Paul (KY – R) introduced new legislation, the REDEEM Act, to divert juveniles away from the adult criminal justice system and ease the path of reentry through early record expunction among other means.

Finally, in addition to supporting state and local efforts, the federal government has recently furthered its own sentencing reform initiatives within both the executive and legislative branches in 2015. This session, Senators Richard Durbin (IL—D) and Richard Grassley (IA—R) introduced the Sentencing Reform and Corrections Act, which would substantially retract certain mandatory minimum sentences in federal prisons among other things. In November, over 5,000 federal prisoners convicted of drug-related felonies will be released early as a result of US Sentencing Commission policy changes instigated last year. They will be the first of an estimated 40,000 to benefit from the recommended lower sentences put forth by the Commission. Though the Commission is independent, this wave of change in the federal judicial system follows an Obama Administration directive to rethink mandatory minimum sentences and increase judicial discretion. Whether these reforms will result in reinvestments in the federal corrections system as in the states is yet to be seen.

Early State Success & Aggregate Effects of Justice Reinvestment

So with all the new laws, large commissions, and federal funding, has justice reinvestment proved its worth? While several states demonstrated or projected individual gains by some measures, on the aggregate, states with justice reinvestment programs have yet to demonstrate clear and consistent improvement over non-participating states. From cost savings to prison population levels to crime rates, the evidenced is promising but so far mixed as to the true collective benefit of justice reinvestment.

Cost Savings

As stated at the outset of this article, the primary reason for justice reinvestment is to reign in in the exploding costs of criminal justice and prison systems across the US. Some states are achieving steady progress in reaching this goal. Others have yet to bring down annual costs but project savings in the millions over the next five to twenty years.

Texas, one of the first justice reinvestment states, decreased annual expenses over the life of its program from $3,754 million in 2006 to $3,431 million in 2014. Comparatively, New Hampshire only decreased expenditures from $106 million in 2006 to $105 million in 2014 but anticipates $10.8 million in savings, and $179 million in averted costs in the coming years. In other states, costs are still rising. With many justice reinvestment efforts so new, however, it is difficult to draw conclusions from short term cost differentials. For instance, though expenditures have increased from $584 million to $609 million since launching its justice reinvestment program in 2011, Kentucky expects saving of $424 million by 2021. Most states similarly have yet to demonstrate results but project high savings over the medium term. According to the Urban Institute, Justice Reinvestment programs funded in part by the federal government will save as much as $4.6 billion over 11 years in 17 states.

Much of the projected savings states report hinge on either prison closures or averting new prison openings due to reduced prison populations. Some states are already succeeding in reducing prison facilities. For example, two prisons were closed in South Carolina in 2012. One facility closed in Vermont, by statute, and four minimum-security prisons closed in North Carolina. Several other states converted prisons to treatment facilities or outposts for community corrections.

Despite these positive reports and some real gains already in certain states, significant costs savings have yet to materialize for justice reinvestment programs on the whole. Justice reinvestment states were slightly less likely to reduce annual costs as compared to non-justice reinvestment states in most cases assessed. For instance, from 2006-2013, justice reinvestment states were only .125 times as likely to reduce prison expenditures than increase expenditures while non-justice reinvestment states were .136 times as likely to reduce expenditures. Though inconclusive, these results may be explained in several ways. Fist, corrections costs are still rising across the board and, at the same time, the sample of states with justice reinvestment programs is perhaps too small to produce reliable statistics just yet.

Another reason that participating states have not yet reaped real and differential savings may be because they are reallocating corrections budgets in ways they believe will be more efficient in the long run. The very name justice reinvestment is born of the intent to “reinvest” savings from reform into improving criminal justice systems. As such, many state legislatures either mandated the reinvestment of savings back into their departments of corrections or set aside percentages of any savings as part of their annual budgeting processes. The Urban Institute report found that $398 million in reinvested funding was proposed across 17 states receiving federal grants. Over $165 million had already been reinvested. Having launched its reform program in 2011, North Carolina already reinvested $22 million from actual savings by 2013. Though it may be too soon to tell whether or not justice reinvestment will slow the growth of and eventually reduce criminal justice expenditures in states across the US, such promising signs in individual states enliven some hope.

Imprisonment Rates

Between 2009-2012, the US prison population began to decline for first time in roughly forty years. For this reason, some argue justice reinvestment has had a positive impact on prison populations nationwide. However, as with cost savings, it may be too soon to tell how much justice reinvestment programs have contributed to this decline. With many simultaneous laws passing legislatures and set to go into effect at different intervals not to mention alterations in external factors, it is nearly impossible to uniquely track the determinants of prison population ebbs and flows. This lack of predictability was illustrated in 2013 as state prison populations increased for the first time in five years while federal prison populations decreased for the first time since 1980.

Despite this uncertainty as of yet, some evidence does seem to suggest justice reinvestment is beginning to have an impact on the number of incarcerated persons across the US. For instance, of those states that have instigated justice reinvestment, over 4.5 times as many state’s prison populations decreased than increased one year after the legislation passed. Some states in particular are seeing great success. Texas’ prison population, which exploded from 50,042 in 1990 to 162,193 in 2006, the year before legislation was enacted, declined to 140, 839 in 2013. Other states such as Kentucky and Louisiana have seen drastic reductions from 20,952 to 12,141 and 39,709 to 18,704 respectively between enactment in 2011 and 2013. Still others have seen more modest progress like Arkansas with a 2013 prison population of 14,295, slightly up from the 2006 baseline of 13,713 but down from the 2010 high of 16,147.

These findings are tempered however, as more states overall are experiencing decreasing prison populations. From 2006 to 2013 the number of states with decreasing versus increasing prison populations was roughly even at 24 to 26 respectively. However, more recently between 2010 and 2013 the ratio shifted to nearly two times as many states with decreasing prisoner populations as increasing, with a rate of 1.27 times as many declining as compared to inclining between 2011 and 2012 alone. Therefore, though some rough evidence seems to suggest justice reinvestment states may be more likely to have declining prison populations, it is too soon to tell with the limited data as of yet unable to illustrate strong patterns over time. Compounding the difficulty of detecting new patterns across states promoting justice reinvestment may be the relatively modest degree of change thus far in a significant number of those states. Most states have not implemented sweeping changes but small or highly targeted policy alterations, sometimes across multiple legislative sessions. This further clouds potential effects on an aggregate scale.

With a small sample size, sometimes modest policy changes, and the limited length of time that most justice reinvestment efforts have been implemented, states and researchers must rely in part on projections for the near future. The Urban Institute projects that, in the 17 states reforming their criminal justice systems through the federal Justice Reinvestment Initiative, a 0.8 to 25 percentage point reduction in prison population will result compared to projected population growth without reforms. However, the think tank also acknowledges that it is too soon to assess the actual impact of such justice reinvestment policies.

Crime rates

As compared to prison populations and expenditures, controlling crime rates is not a direct goal of justice reinvestment. This may largely be attributed to the fact that crime rates overall fell dramatically in the US since a boom in the 1980s. Crime rates continued to fall through 2012 with the exception of a bump in both property and violent crime directly preceding and during the worst of the US recession between 2005 and 2008.

Though crime rates are not a direct concern of those crafting justice reinvestment legislation, any increase in crime in participating states would be a negative indicator that these new programs may have unintended consequences. As with prison expenditures and populations, however, differential trends in crime rates are difficult to decipher for justice reinvestment as compared to non-justice reinvestment states. Between 2006 and 2012, violent crime in justice reinvestment states was two times as likely to decline as increase. Comparatively, such crime was 2.5 times as likely to decline in non-justice reinvestment states. While violent crime was more likely to decline in non-justice reinvestment states, property crime was less likely to decline. Property crime was .8 times as likely to decrease as to increase in justice reinvestment states while it was only .14 times as likely to decrease as increase in non-justice reinvestment states. With sample sizes as small as 9 however, these statistics are difficult to draw clear conclusions from once again.

Despite the lack of clear and identifiable trends in crime as it relates to justice reinvestment efforts across the states, some assuring research indicates negative signs have not materialized even if positive signs have also not. For instance, the Pew Center on the States found that between 2000 and 2010 all of the nearly twenty states that saw imprisonment decline also saw crime decline. Therefore, while definitive results are still elusive, we may infer that justice reinvestment has, at the least, not caused a spike in criminal activity in the US in recent years. As crime reduction is at best a tertiary goal of justice reinvestment, this may be the best result likely to occur.

Recidivism

Recidivism, or the rate at which released prisoners return to prison, is a consistent problem in the United States. According to a landmark 2005 study by the Bureau of Justice Statistics, over 75 percent of prisoners were rearrested within five years of release. Of those rearrested, over 50 percent were arrested in the first year alone. In a more recent 2011 study, the Pew Center on the States found that recidivism rates were consistently above 40 percent (1 in 4) across the US from the 1990s through the early 2000s.

Though, once again, no comprehensive data is yet available, some evidence of success within a limited number of states is beginning to emerge. North Carolina, for example, decreased its recidivism rate by nearly 7 percentage points between 2006 and 2010. The state has particularly led the way in reducing recidivism due to technical violations of parole from 19,045 in 2010 to 9,458 in 2013. Subsequently closing nine correctional facilities, Nort

Though, once again, no comprehensive data is yet available, some evidence of success within a limited number of states is beginning to emerge. North Carolina, for example, decreased its recidivism rate by nearly 7 percentage points between 2006 and 2010. The state has particularly led the way in reducing recidivism due to technical violations of parole from 19,045 in 2010 to 9,458 in 2013. Subsequently closing nine correctional facilities, North Carolina was able to reinvest in 175 additional probation officers. The state also worked to create and financially support five local reentry councils, which proponents cite as a potential reason for the decline in new offense revocations from over 4,100 to less than 3,500 between 2010 and 2013. Other states also touted individual progress on recidivism. Pennsylvania reported a 7 percent decline in 1-year rearrests as well as a 2 percent decline in two-year rearrest rates between 2007 and 2011. Georgia too has seen an over two-percentage point decline in recidivism.

Though positive signs, these individual success stories do not present the full picture of the impact that justice reinvestment initiatives have on recidivism. Too little evidence is yet available to identify consistent patterns across states and years as is true for other major indicators from crime to incarceration rates to corrections spending. As one interesting counterpoint, for instance, Georgia experienced reduced recidivism for several years before state leaders officially launched justice reinvestment efforts. This may be due, in part, to the piecemeal approach multiple states employed to improve their criminal justice systems before wholesale legislation or other major measures were adopted. It is even more difficult to decipher the meaning of recidivism rates across the US because states with a greater propensity to incarcerate low-level non-violent criminals are likely to have lower recidivism rates than states that primarily imprison violent criminals. On the other hand, states that have shorter parole periods and use re-imprisonment only as a last resort are also more likely to have lower recidivism rates as compared to states that have long probation periods or re-imprison more, according to the Pew Center on the States. Thus, justice reinvestment policies may have either a negative or positive impact on recidivism rates, or both. As such, only time and meticulous data analysis may reveal the true impact of justice reinvestment efforts on recidivism.

Summing Up the Early Effects

Taken together, there is not yet enough empirical evidence that justice reinvestment has positive effects on the neither recidivism rate nor negative consequences upon the crime rate across states. At the same time, there is not sufficient evidence on the aggregate, beyond some impressive individual cases and promising projections, to suggest that justice reinvestment is beginning to decrease state prison expenditures and populations significantly.

While at this stage individual developments are still merely seeds of hope, the justice reinvestment cause has garnered sufficient evidence and research to pique the interest of any lawmaker or bureaucrat searching for answers and solutions. With the momentum justice reinvestment has acquired, the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ new data improvement initiative taking off, and further data likely to be captured over time, the benefits may soon become clear of these new evidenced-based efforts to fix a criminal justice system long in need of modernization and reform.

Conclusion

Perhaps more than in any other policy area, states across the US are taking the lead to reimagine, refine, and reinvest in their criminal justice systems long in need of reform. They are doing so through promoting evidenced-based practices and rewarding cost-effective solutions, setting a model for smart policy-making in an era of big data and unprecedented technological access. While little in the way of definitive trends has emerged demonstrating the benefits of justice reinvestment across states, some promising early effects and projections in individual states strengthens the momentum for reform. With new federal funding now available as a result of these early and exciting developments, the number of states reinvesting in corrections is blossoming. With most state efforts still young, time will tell the true benefits of justice reinvestment policies. Nonetheless, states have demonstrated some real progress and spurred momentum in a policy arena long in need of reform, enlivening hope in a criminal justice system badly in need. One can only hope the innovative and performance-driven approach adopted by these leaders will inspire analogous reforms in juvenile justice, policing, arms control, and other related criminal justice policies, ultimately changing the national dialogue from one of anger, distrust, and despair to one of collaboration and hope. Dare to dream.

Stephanie Keller Hudiburg is a recent graduate of the McCourt School where she focused on community and economic development policy, public sector innovation, and performance management as the Co-Director of the McCourt School Policy Innovation Lab and a Research Fellow with the Center for Public and Nonprofit Leadership. Before moving to DC, Stephanie served as the Chief of Staff to a State Senator representing Boston in the Massachusetts Legislature. She is now the Director of Programs and Partnerships at The Real Estate Council in Dallas. Stephanie is a state and local policy enthusiast, writing on several related innovations and reforms for this series.

i cant see how any of our drug offenders can be any worse than terrorist yet the terrorist are released from prison and our government know that they are going home join others terrorist to attach American cutizens again. Most of the drug offenders love American and would die to protect her but we have such a distorted view on crime. If you do not believe so just look uo what our military uses for years the “Go Pill” it is same as meth its an amphetemine to keep our pilots awake on their mission yet once a pilot is no longer in military does that make it not okay after the government started the pilots addiction. Far to many politicians, and other use this double standard to hide their own addictions. As the saying goes cast not a stone while standing in your glass house. There is no difference and only seconds between them and these offenders, except the offender probably respects our constitution more and doesnt take it fir granted like politicians do!