To understand Ferguson—the place itself, the events that transpired there in the last year, and its resonance as a metaphor for twenty-first century race relations—one need go no further than the Department of Justice’s devastating Investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, released last March. While the report’s exploration of systematic racial bias in the Ferguson police force made headlines, important questions remained unanswered. Why was local policing so starkly animated by the assumption that African-Americans were threats and not citizens? Why were local police not only harassing African Americans, but plundering them one traffic ticket at a time in order to keep the lights on at City Hall?

The answer to the first question is deeply rooted in the long history of racial segregation in Greater St. Louis. Throughout the last century, realtors, developers, and white property owners erected elaborate obstacles to black property ownership and occupancy. These restrictions, over time, evolved into an ethical obligation of private realtors, lenders, and insurers; an organizing principle of both local zoning and federal housing policies; and a key determinant of value whenever property was taxed, “blighted” for redevelopment, or redeveloped. The net effect was not just the spatial segregation of metropolitan St. Louis by race and class, but also a cascade of disinvestment and disadvantage on the City’s northside, an uneven and fragmented pattern of residential development and land-use zoning in the suburbs, and a yawning racial gap in local wealth.

In this context, inner suburbs like Ferguson became zones of dramatic racial transition. Local progress on fair housing, especially after Jones v Mayer (1968), began to erode the “Berlin Wall” of racial occupancy that erected itself between the City and suburban St. Louis County. At the same time, the collapse of the residential base in the City itself, the decommissioning of the City’s “big box” public housing in the 1970s, and the displacement spurred by urban renewal all put enormous pressure on the region’s stock of affordable housing. African-Americans—displaced by neighborhood collapse and public policy, and impoverished by their exclusion from the first generation of federal housing subsidies—filtered into homes and apartments in ageing “second-hand suburbs.”

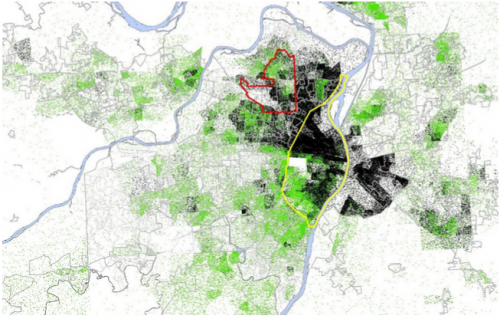

Racial Occupancy by Block Group, 2010

The result? The patterns and mechanisms established on the City’s northside drifted into North County, where they were reinvented and reestablished. In the bargain, the consequences of segregation—including concentrated poverty, limited economic opportunity, paucity of public services (except heavy-handed policing) and political disenfranchisement—moved to the inner suburbs as well. In and around Ferguson, African-Americans settled overwhelmingly in the apartment complexes along Maline Creek in south Ferguson and Kinloch, and in pockets of single-family housing east of West Florissant Avenue and south of I-270. With this racial transition came a replication and extension of the tangled disadvantages—poverty, unemployment, inequality–long-faced by African-American on the City’s northside.

The answer to the second question—regarding the predatory nature of local policing—is more complicated. Certainly it is rooted in the common and discomfiting presumption that African Americans are lesser citizens, a stereotype starkly on display in transitional settings like Ferguson; at minimum an offense to property values, at worst a threat to public safety. We know, for example, that the Ferguson Police Department’s predilection for “suspicionless, legally unsupportable stops” (in the words of the Justice Department) has yielded arrest and citation rates that fall almost exclusively on the city’s black residents. And we know more broadly that this pattern of policing leaves many poor African Americans in a perpetual state of custodial citizenship—as likely to be dodging or avoiding state surveillance, as benefitting from state programs.

But there is more than just racist policing at work here. In one respect, such aggressive policing is characteristic of our neoliberal moment, in which state power increasingly conditions or disciplines the poor to the need and demands of the market. But, it also a function of a local and fragmented fiscal crisis. Ferguson authorities lean heavily on their most marginal citizens not because of racial animus, but because they need the money. Local property tax revenues have been savaged by state-imposed fetters (Missouri’s 1980 “Hancock Amendment” capped property tax growth and the ability of local governments to raise rates), by declining property values in North St. Louis County, and by a “beggar they neighbor” pattern of commercial tax abatements.

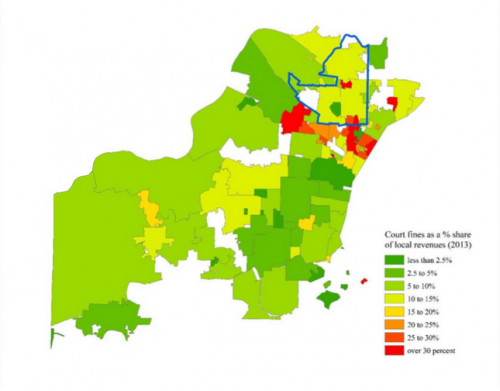

Court Fines as a Share of Local Revenues (2013), St. Louis County

The result? As a consequence of development and demographic patterns, the municipalities and school districts of North St. Louis County (including Ferguson and the Ferguson-Florissant school district) combine property values well below the metro average with tax rates well above the county average. Ferguson municipal officials argue against the policing and court reforms recommended by the Justice Department—not out of defensiveness about past practices, but because choking off that revenue stream “would financially ruin the city.”

# # #

Where does this leave us? The troubling reality, looking forward, points to longstanding and dramatic damage, much of which is intentional. The racial wealth and housing gap reflects generations of private and public discrimination. Our hollowed-out inner cities reflect a half-century of segregation, deindustrialization, and underinvestment. And both outcomes, heavily subsidized by federal, state, and local dollars in housing and urban renewal, are now largely off the table. The resources to undo the damage, in short, are scant.

Understanding the deeper roots and implications of Ferguson suggests, at the very least, that affirmative hiring in suburban police departments or more widespread use of police body cameras serve as meagre or superficial solutions. It is not, in the end, about the culpability of one police officer or the culture of one police department. Rather, local demographic and development patterns, which yielded an ongoing confrontation in Ferguson between a nearly all-white police force and a majority-black citizenry, suggest the enduring reach of older patterns of local segregation and discrimination. And the pattern of local policing, reflecting both that racial history and more immediate political and fiscal pressures, underscore the devastating and tragic implication of neoliberal governance in local settings.

This said, our hands are not completely tied. As underscored by a generation of urban scholarship, we could accomplish a lot just by governing our cities as cities—as organic economic and social and demographic regions. Municipal fragmentation creates both incentive and opportunity to poach and hoard local resources. And, in the resulting games of musical chairs with local investment or beggar-thy-neighbor with local zoning, everyone loses.

Some of our urban policies already exist regionally. Few, for example, question the efficiency or equity of a metro-wide water and sewage district, or a metro-wide transportation planning agency. If we pursued other policies, such as land use zoning, school funding, and economic development, on the same scale, we might begin to displace destructive local competition—the brunt of which is born by our most vulnerable citizens—and replace it with a stronger commitment to the public good.

Colin Gordon is Professor of History at the University of Iowa. He is the author of Growing Apart: A Political History of American Inequality (Institute for Policy Studies, 2013); Mapping Decline: St. Louis and the Fate of the American City (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008); Dead on Arrival: The Politics of Health in Twentieth Century America (Princeton University Press, 2003), and New Deals: Business, Labor and Politics, 1920-1935 (Cambridge University Press, 1994). He has written for The Nation, In these Times, Z Magazine, Atlantic Cities, and Dissent (where he is a regular contributor). Colin Gordon received his PhD from the University of Wisconsin-Madison in 1990. His web page is www.colin-gordon.org