Childhood obesity in the United States is a growing concern for policymakers, teachers, public health officials, and parents. Over the past decade, approximately 17 percent of children and adolescents in the US—or 12.7 million individuals—were categorized as obese, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. This is about triple the rate in 1980. Childhood obesity can lead to many negative health outcomes, including high blood pressure and cholesterol, breathing problems, greater risk of social and psychological problems, and joint problems.

As policy leaders continue to look for ways to manage the costs and challenges associated with this public health crisis, educators are increasingly turning to physical education (PE) in schools as part of the solution. Yet, dedicating more time to PE takes away from traditional classroom subjects, such as mathematics and reading. For decision makers interested in enacting policies that allocate more time to PE classes, studies revealing the relationship between PE class time and student academic achievement will help contribute to a broader understanding of the policy implications. My research aims to help answer this policy question by examining whether state laws addressing PE time requirements for elementary school students are related to average state mathematics test scores for fourth graders. As education leaders and policymakers consider reforms that dedicate more time to PE in an attempt to improve health outcomes, they will need to understand the implications for academic performance. My research tries to further this understanding.

Exercise, Classroom Time, and Academic Achievement

Exercise has long been known to improve physical health. But according to Ratey and Hagerman’s 2008 book, Spark: The Revolutionary New Science of Exercise and the Brain, recent research reveals that going for a run or playing basketball might have equally powerful effects on the brain. In fact, exercise helps prepare the brain for learning by improving alertness, encouraging necessary cell activity, and spurring the growth of new cells.

Exercise has been a component of the federal government’s public health agenda for about the last two decades. Since 1995, physical activity advice has been a part of the Dietary Guidelines for Americans. In 2008, the US Department of Health and Human Services deemed the research addressing the benefits of physical activity strong enough to develop standalone guidance for exercise. The National Conference of State Legislatures reported that in 2010 and 2011, 16 states enacted laws related to PE, physical activity or recess.

And most recently, physical activity received national attention as a result of First Lady Michelle Obama’s Let’s Move! campaign, which aims to end the problem of childhood obesity in the United States within a generation.

A mounting body of literature continues to illuminate the positive role that exercise can serve in terms of both brain health and physical wellbeing. However, if schools dedicate more time to PE, students will likely spend less time in the classroom on traditional subjects. As educational leaders and policymakers consider policies that dedicate more time to PE in an attempt to improve health outcomes, they need to understand impacts of the tradeoff and implications for academic performance.

My research explores whether state laws addressing PE time requirements for elementary school students are related to average state mathematics test scores for fourth graders. I build on previous research focused on time spent in PE class and academic outcomes at the individual and school level by examining the effects of state-level policies. Results from program evaluation studies indicate that, at a minimum, time in PE class does not harm academic achievement. However, researchers have yet to thoroughly examine potential associations between state PE policies and classroom performance. The results from this analysis may help state leaders to understand whether the level of commitment to PE classes has any unintended consequences for academic outcomes at the elementary school level.

Empirical Analysis of State PE Laws and Academic Achievement

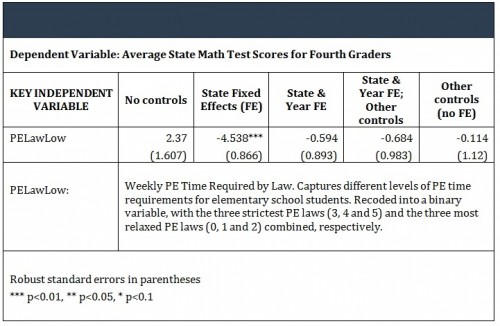

The analysis for this paper makes use of state-level data from 2003, 2005, and 2007, drawing from a number of sources, including the U.S. Census Bureau, U.S. Department of Education, U.S. Department of Labor, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Annie E. Casey KIDS COUNT survey, the Council of State Governments, and the National Conference of State Legislatures. The key independent variable in its original form is ordinal and comes from the Classification of Laws Associated with School Students’ Physical Education Related School Policy Classification System (PERSPCS), a project of the National Cancer Institute (C.L.A.S.S., 2012). The range for this variable is defined as follows: 0 indicates no PE time requirement for school districts in state law; 1 indicates that the state recommends PE time requirements or lays out PE time as an option; 2 indicates the state requires public school districts to provide PE for less than 60 minutes per week or that the state requires PE but without a specified time requirement; 3 indicates a requirement of 60 to 90 minutes per week; 4 indicates a requirement of 90 to 150 minutes of PE per week; and 5 indicates a minimum of 150 minutes per week. To ease interpretation of the coefficient for this variable, I re-code it as binary. Specifically, state- years with the three strictest PE laws (3, 4 and 5) are coded as 0, and state years with the three most relaxed PE laws (0, 1 and 2) are coded as 1.

To measure academic achievement, my key dependent variable, I use state-level average fourth grade math test scores. Since state PE law data and state standardized test score data are both available for only three years—2003, 2005, and 2007—I use information collected for these three years in my analysis. The sample size for my state-year panel is 153: 50 states and the District of Columbia, each with three years of data.

This analysis makes use of state and year fixed effects, as well as a number of control variables to proxy for the health, economic and demographic factors that likely are related to both state PE laws and academic achievement. For some models, I also treat my data as ‘cross-sectional’ by eliminating state fixed effects dummies, and adding in time-varying climate and geography control variables to help reduce bias.

Results and Analysis: Finding of No Effect

The state and year fixed effects and cross-sectional analyses in this study provide no evidence of a relationship between state laws addressing weekly PE time requirements for elementary school students and average state fourth grade mathematics scores. The models employed here yield consistently small and non-significant associations between state-level PE laws and mathematics scores.

There are a number of potential reasons for this lack of association, including the possibility that state PE laws truly have no bearing on academic achievement. While it appears that no other studies have directly examined the question I try to answer with this paper, many other papers over the last several years have looked at the relationship between PE and academic achievement at an individual or program level. For example, the Centers for Disease Control conducted a meta-analysis concluded that most studies examining associations between physical activity and academic achievement find non-significant or positive associations. The results of my study are consistent with this meta-analysis, as well as the broader literature on PE and academic achievement.

Another potential reason for my findings of no association between PE laws and mathematics test scores is the limited amount of data that is available. The data-sets I used to generate variables for the dependent variable and key independent variable provided data for a limited number of years. And more than 80 percent of states maintained the same PE laws over all three years. Had data been available for additional years, both the fixed effects and cross-sectional analyses would be able to exploit additional variation both within and between states, enabling more precise estimates.

Omitted variable bias also likely affects the results of this analysis. One major variable that I was unable to control for was a measure of school districts’ level of authority regarding physical education. If school districts choose to make PE a priority on their own, state PE laws may have little influence on the actual time elementary students spend in PE classes. As such, it may be that states with weaker PE laws still have strong physical education programs at the local level.

State lawmakers may find these results valuable to the extent that they provide some assurance that PE laws for elementary school students do not appear to harm academic achievement. In other words, for policy officials who choose to use PE laws as a strategy for improving physical health outcomes, the results from this analysis indicate that such policies probably do not have a detrimental effect on classroom performance.

To make more a more definitive statement about PE and academic achievement, however, researchers need access to more and better data. With more data points, one could conduct a variety of subsample analyses that might uncover additional nuances in the relationship between state PE laws and academic achievement. Examining the role of school district policies and characteristics may also prove useful in understanding the effect of PE laws at a lower level of aggregation. Finally, just as this study did not examine implementation of PE laws, it also did not include any measure of quality of PE programs. Future research might consider the quality of programming that results from different kinds of PE laws and whether quality is associated with better or worse academic and/or health outcomes. I would like to see states and the federal government continues to collect data about PE and academic achievement, because more information can drive better solutions to our country’s childhood obesity problem.

Ingrid is a former graduate of Georgetown University and is now Communications Director for Representative Rick Larsen in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Learn about the importance of quality physical education in the free documentary No Excuses! which follows a transformation project at one school in Harlem: http://www.supportrealteachers.org/no-excuses-a-film-about-qpe1.html

Nice post. I used to be checking constantly

this blog and I am impressed! Extremely helpful information specifically

the remaining section 🙂 I care for such information a lot.

I was seeking this particular information for a long time.

Thank you and good luck.