Gabriel Yorio-Gonzalez holds a Master’s degree in Policy Management from Georgetown University and currently works as a public sector STC at the World Bank.

During the financial crisis of 2008-2009, Latin America managed to do well relative to the rest of the world. Governments used fiscal policy as the workhorse for ensuring macroeconomic stability throughout the last decade. However, in the aftermath of the crisis, reduced fiscal flexibility caused governments to engage in a new wave of fiscal reforms. When economies began improving, governments had already raised taxes, cut expenditures, or increased debt. So as a complementary action, some practitioners urged governments to strengthen their fiscal sustainability path from a public management perspective. According to the International Monetary Fund, the crisis highlighted public financial management (PFM) as one critical element to buttress public finance equilibrium, especially for reducing the effects of budgetary institutions on fiscal outcomes.

This situation led practitioners to the revise the general budget cycle and reduced the treasuries’ abilities to control the budget. As part of this risk-mapping approach, exogenous elements such as legislative voting procedures were identified as one possible sources of risk, especially the practice of logrolling when voting on budget. Legislative logrolling is a common practice used to pass legislation, by combining within a single bill several unrelated or unpopular provisions that could not pass on their own. Therefore, if logrolling is a common practice in Latin America it may be one of the causes affecting fiscal balance outcomes.

The influence that legislative voting procedures have on public financial management in Latin America is still indeterminate, as only a few empirical studies have tried to measure their impacts on fiscal discipline. Traditionally, during the last 20 years, the PFM reform agenda excluded legislative voting procedures as risk sources and focused instead on endogenous inefficiencies. This article presents a research agenda for further empirical analysis to explore if voting procedures have caused variability in fiscal outcomes and shaped public financial management within the region. The divergence in legislative processes may account for the different variability levels between voted and observed budgets. This article will inform further empirical analysis by mapping Latin American countries according to the stature of their treasury department, legislative voting processes, and fiscal discipline outcomes.

Legislative logrolling as the cause of distortionary biases in budget planning

The last financial crisis defied the capability of Latin American countries to maintain macroeconomic stability. Economic distress caused increased fiscal pressures because decreasing revenues challenged governments’ abilities to execute expenditures and maintain public finance equilibria. The crisis raised a debate about the effectiveness of PFM as a means of supporting fiscal sustainability.

This debate led to a comprehensive revision of the budgeting cycle, to identify holdups affecting the efficacy of traditional PFM reforms such as the Treasury Single Account (TSA). In the late 1980s, the US government implemented a TSA for the first time as part of a management modernization agenda seeking to reduce deficit and debt. For example, the TSA helps the treasury to increase money fungibility and improve cash management by reducing idle balances and overborrowing. This became a point of inflection in PFM history as the TSA has the potential to affect many aspects of monetary policy. For one, it allows the treasury department to withdraw large amounts of money from the financial system. Most countries with TSAs also deposit the resources in their central bank facilitating money supply control.

Today, a new debate is taking place beyond the current scope of PFM, focusing more on the political aspects of budgeting at the legislative level. For instance, different voting procedures in legislatures can lead to different outcomes. In the case of the voting process on budget, it is possible for distortionary biases to arise on two particular issues: determining budget size and allocating appropriations. These problems are caused by logrolling between legislative members when discussing and voting for budgets.

During the planning stage of the budget cycle, the executive branch estimates macroeconomic variables to frame the budget. Afterwards, the budget proposal is sent to the legislative for voting. In this stage, the budget can undergo modifications due to the logrolling practice. Logrolling appears when legislative members accommodate additional expenditure – to satisfy constituencies’ requirements – by voting on unrealistic revenues. Since there is an obvious effect on fiscal equilibrium and PFM, countries are interested in reducing this practice by modifying voting processes. For example, in 1974 the United States reformed budget procedures by changing the sequence of congressional votes on the budget. At that time, the US Congress would vote on a series of appropriations bills first, and then determine the overall size of the budget. The reform required Congress to vote on the overall size of the budget at the beginning of the process, and then on appropriations afterwards. This, by enforcing ex ante discipline by tying expenditures to a realistic revenue estimation. After the US Congress modified this procedure, several US states established a “single subject” rule (SSR) clause in their constitutions. This clause required that every bill address only one specific subject in an attempt to reduce the logrolling practice.

Sequence in legislative voting on budget matters

Logrolling is likely to surge when the legislature conducts the discussion and voting process in a “package,” by addressing revenues and expenditures in parallel. When this happens, the legislature is more likely to vote on appropriations first and define the total budget size later. Doing this increases the possibility of inflating the budget, which consequently bottlenecks PFM efficiency, as governments – especially the treasuries – know expected revenues would not materialize and that cash shortfalls would appear.

For this reason, moving from a budget “package” to a two-stage discussion procedure under a SSR may seem to be one way to vote a realistic budget. The SSR is expected to induce the legislature to discuss first revenue, then debt, and finally expenditures. By doing this, the SSR would reduce the propensity to overestimate revenues and its pernicious effects on fiscal sustainability, budget execution, and over borrowing. Obviously, logrolling may persist if the legislative members anticipate this process by inflating the revenues in the first stage. For this reason, fiscal rules and a checks and balances system are keystones.

Thus, divergence in legislative discussion processes and the existence of logrolling may account for different variability levels between voted and observed budgets in Latin America. For example, some countries have modified their legislative voting procedure to an SSR approach, while other countries in the region maintain a “package” voting process. This has not only created variability in fiscal outcomes but also different organizational structures in treasury departments. For example, some empirical studies have attempted to measure the effect of voting procedures on fiscal outcomes and PFM. In the case of Latin America, evidence suggests that in the ’80s and early ’90s, fiscal discipline in the region was associated with procedures that limited the role of the legislature in expanding the size of the budget. Additionally, the control of the treasury appeared to play a crucial role in limiting budget biases.

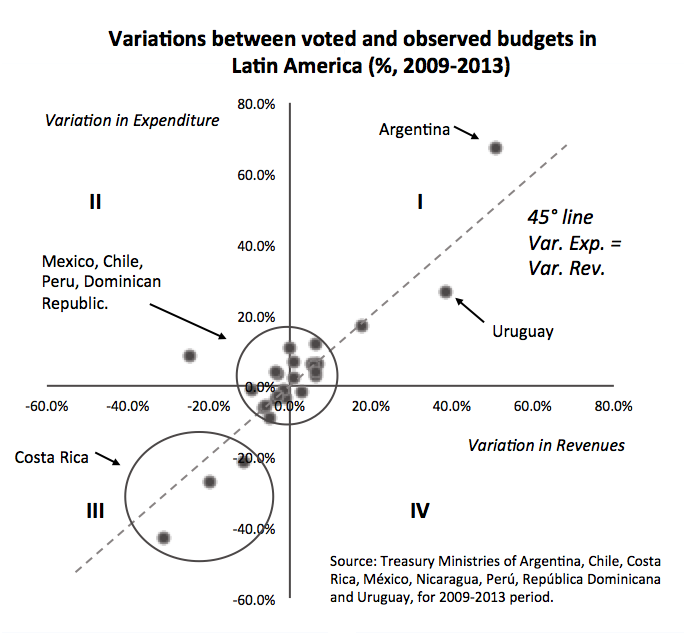

Since logrolling can cause greater variability between the voted and observed fiscal aggregates, countries with two-stage discussion procedures should experience less variability compared to those with “package” voting procedures. The following graph shows the variations for different countries from 2009-2013. In the absence of debt issuing, if legislative members voted on a balanced budget, the overestimation of revenues should be equal to the overestimation of expenditures (45-degree line). A negative variation means the voted fiscal aggregate was greater than the observed, which means an overestimation. To that extent, observations moving away from the origin indicate greater variability.

The graph shows that most of the observations are situated in Quadrants I and III. However, there are four possible cases:

- Quadrant I. Budgets with underestimation of both revenues (+) and expenditures (+). This quadrant shows budgets in which observed fiscal aggregates are greater than the voted. This may be caused by path-dependence planning procedures, political tension, or revenue dependence on commodities prices. Countries in this quadrant include Argentina, Chile, Mexico, and Uruguay.

- Quadrant II. Budgets with underestimation of expenditures (+) and overestimation of revenues (-). This case seems counterintuitive since expenditures are underestimated while revenues where overestimated. Some possible explanations may be the effects on economic shocks on fiscal outcomes or sovereign funds execution dynamics. This quadrant includes the budgets of Chile in 2009 and Argentina in 2012 and 2013.

- Quadrant III. Budgets with overestimation of both revenues (-) and expenditures (-). This is the case where logrolling when voting on a budget might be the explanation for overestimation. This quadrant shows countries like Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua, and Peru.

- Quadrant IV. Budgets with overestimation of expenditures (-) and underestimation of revenues (+). This quadrant shows the case of Chile’s budget in 2012. This may also be explained by the execution dynamics of sovereign funds.

Countries like Mexico and Chile who have a two-stage voting process are expected to reflect smaller variability and no overestimation of fiscal aggregates, as is shown in the graph. On the contrary, if Costa Rica, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and Peru, still maintain “package” voting processes, this may explain the greater variability on fiscal outcomes and overestimation of fiscal aggregates. These countries would require stronger budget control by the treasury in order to maintain fiscal sustainability.

Logrolling impacts transcend budgeting processes and PFM efficiency

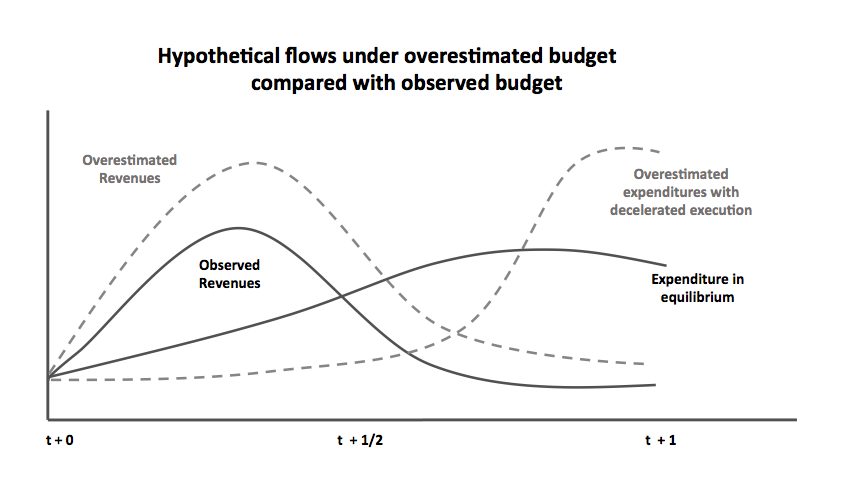

The persistence of overestimated revenues and expenditures has influenced the organizational functions of treasury departments and PFM throughout the region. Since voted budgets may be difficult to reject, treasuries will influence budgets by rationing cash, taking a risk-averse position with the inflow of revenue. For example, budget execution will slow down – as will public spending – until the treasury has a good approximation of the real annual revenue collection. (This would occur by the beginning of the second half of the fiscal year because of the seasonality of cash inflows.)

The practice of cash rationing would modify the natural seasonality of the flows and push expenditure concentration to the second half of the fiscal year. Therefore, the risk of cash shortfalls or excessive debt increases.

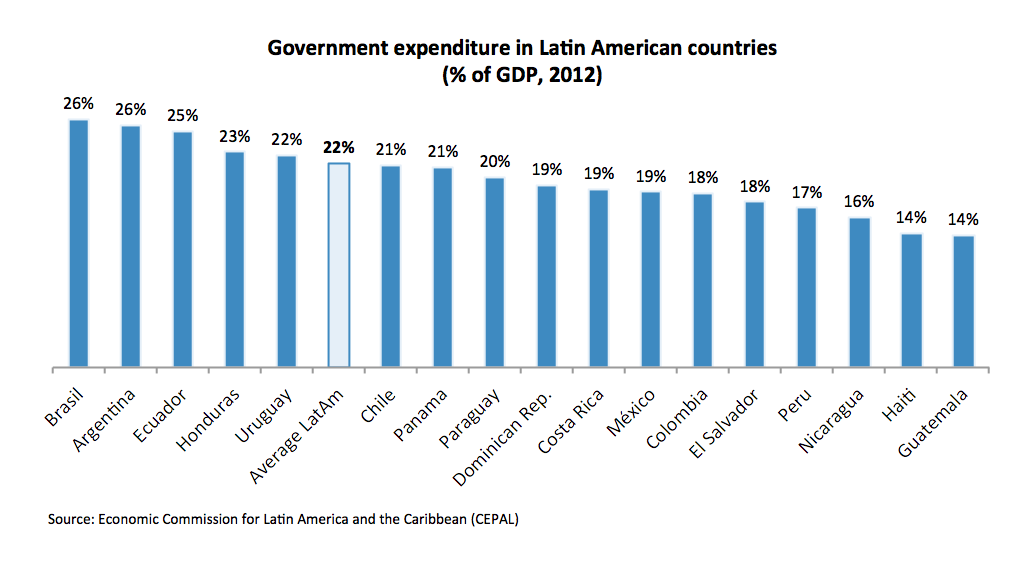

The impact of logrolling goes beyond PFM since slowing down public expenditure can affect economic growth. This is especially true as the size of Latin American government expenditures are usually a significant portion of its overall domestic economy (22 percent of GDP on average).

Further empirical research should include Latin American legislative voting processes and the effects on budgets and PFM

A comprehensive revision of the budgeting process is crucial in order to cope with fiscal aggregate distortions, particularly during legislative discussions where logrolling may emerge. Further empirical analysis categorizing Latin American countries according to legislative discussion processes would help to quantify logrolling impacts.

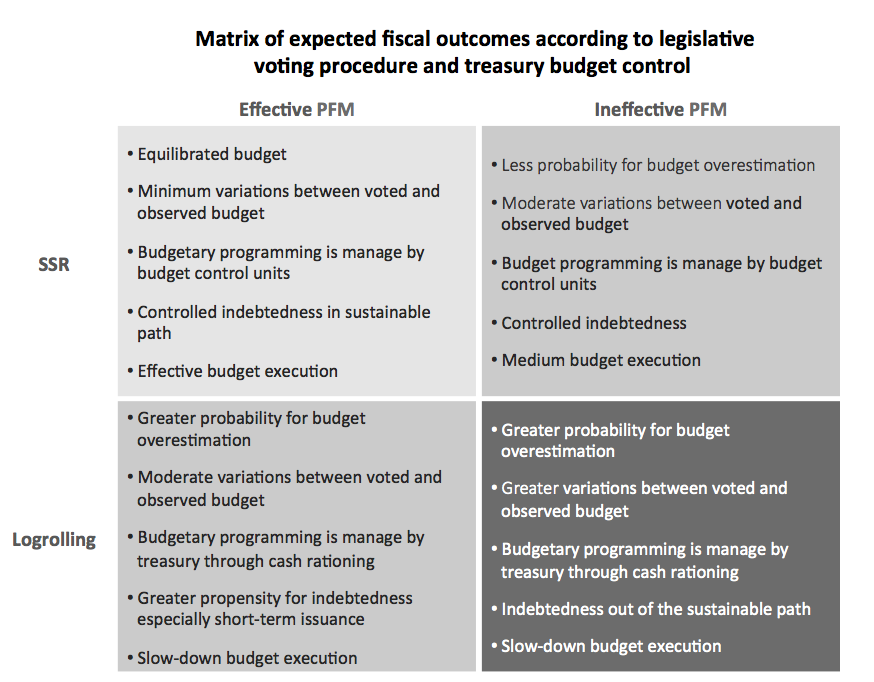

The following matrix summarizes the PFM profiles of countries that have changed their voting processes and strengthened the stature of their treasury department. The matrix proposes a conceptual design to map expected outcomes and possible causal relations. For example, countries with SSR and a stronger treasury control may perform better as opposed to countries with logrolling and a weaker treasury control, while intermediate cases may show a mix of opposite results.

This article is a brief of the Policy Note “Budget Programming and Execution in Treasury Management,” presented by the author at the V Forum of Governmental Treasuries of Latin America 2014 (FOTEGAL) in Montevideo, Uruguay.

Gabriel Yorio-Gonzalez holds a Master’s degree in Policy Management from Georgetown University and currently works as a public sector STC at the World Bank.

As soon as I detected this site I went on reddit to share some of the love with them.