By Chad Hughes

Over the past few years, a pernicious mischaracterization of Detroit has spread like wildfire around the internet and major news outlets (including multiple articles from The New York Times The Economist, The New Republic, The New Yorker, and Forbes). Time and time again, we are told that Detroit is physically huge and that its massive size is one of the core problems that the city must manage. The reality, however, is that Detroit is a perfectly normal-sized American city (if not a little on the small side). Furthermore, because of suburbanization, economic segregation, and the way that American municipalities pay for local services, Detroit would be in a far better position if it were as abnormally large as many journalists claim.

As a staunch urbanist (read: density snob), I often downplay places like Houston (600 square miles of land area) and Phoenix (517 square miles). They are among the top five most populous American cities, but only because they comprise such enormous land areas. However, because the American political and cultural landscape of the 20th century (and, unfortunately, of the early 21st century) largely encouraged suburban sprawl, there are enormous benefits to being, well, enormous. Those cities that were able to respond to the dispersal of their populations by expanding their geographic size are in a far better position than cities whose boundaries remained unchanged. The reason is simple: Fewer of a region’s taxable resources fall outside the reach of the tax regime of a central city, if that city is a geographic behemoth.

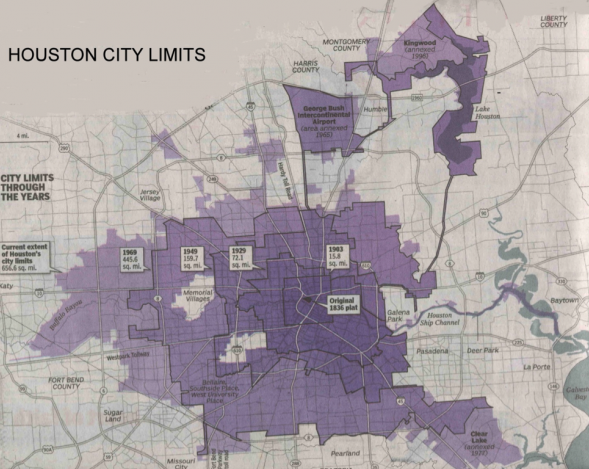

Houston, for example, has done a remarkable job of expanding its physical boundaries to maintain access to the taxable resources of its sprawling region. The city has grown from less than 70 square miles of land area in 1929, to the 500 square mile monster that it is today. Detroit has not annexed a single inch of land since 1926, and as a result has become dangerously isolated as its regional population has dispersed. While the Detroit Metropolitan Statistical Area population has grown by 80 percent since 1930, Detroit’s population has declined by 57 percent. Over the same period, the Houston Metropolitan Statistical Area population has grown by over 1200 percent and the city’s population has grown by 650 percent.

Still Growing: Houston’s Twentieth-Century Geographic Sprawl Has Helped the City Retain a Greater Portion of Its Region’s Tax Base

Source: Adapted from InnerloopHouston.com, Note: Above figures include land and water area

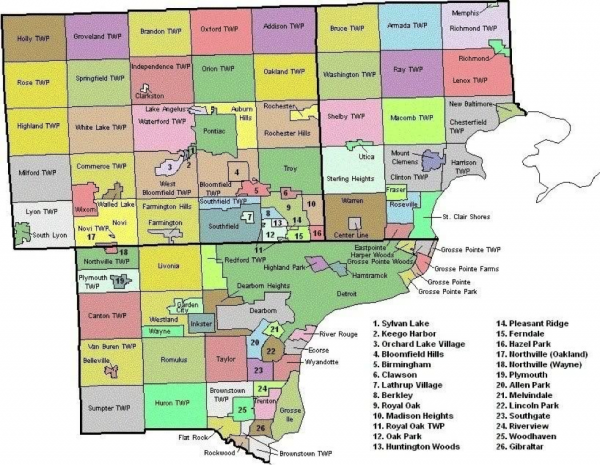

The more Detroit (the city) and Detroit (the metropolitan region) overlap, the better off the city would be. (Unless otherwise noted, by Detroit metropolitan region I mean the three county [Macomb, Oakland, and Wayne] area that comprise the city of Detroit and most of its suburbs. This region covers 1900 square miles and has a population of 3.8 million people.) This is not to say that sprawl is valuable for a city. But for a city’s borders to expand with its metropolitan population is far better than watching hopelessly as all of its taxable resources continue to flee. Currently, the Detroit metropolitan region’s 3.8 million people are spread across 130 municipalities that cover 1900 square miles of land. A 139 square mile city of Detroit with 3.8 million people would certainly be preferable to a 1900 square mile city of Detroit with 3.8 million people. Unfortunately, that kind of migration from suburb to city is not realistic.

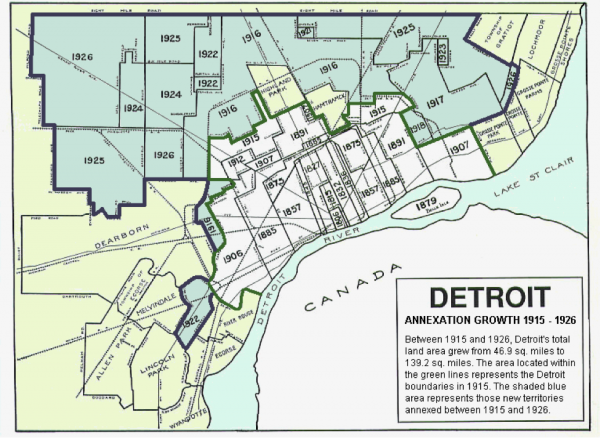

Unlike Houston, Detroit’s Political Boundaries Have Not Expanded Since 1926, Even as the Regional Population (and Tax Base) has Dispersed

Source: DetroitTransitinfo.org

Similarly, it is no longer politically feasible for Detroit to annex its wealthier suburbs. As such, there needs to be a way to increase the contributions of the middle class and wealthy suburbanites living beyond the city’s borders. Michigan should impose a dedicated regional tax (income, sales, or property) with revenues being funneled to the central city.

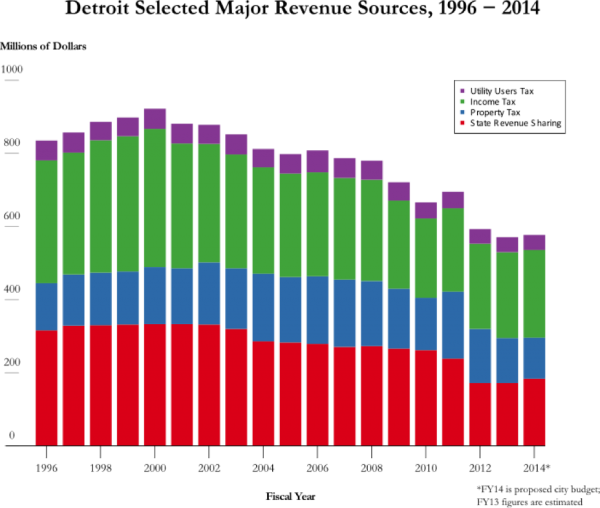

Detroit’s utter lack of revenue sources has led it into a death spiral of higher taxes and costs, lower revenues, and poorer services that culminated in bankruptcy. Unfortunately, Michigan’s response to this bankruptcy has been to utilize “emergency managers” to undemocratically enforce austerity in the short-term without providing a long-term plan for relief. Detroit does not need an emergency manager. Detroit does not need a bailout. Detroit does not need austerity. Detroit does not need charity. Ultimately, the city needs revenue. Until the region provides a stable revenue source, the city will continue to limp from crisis to crisis even as the rest of the region recovers.

Sizing Up Detroit

Most recently, we find the “Detroit is huge” mischaracterization in Ben Austen’s excellent New York Times Magazine piece about the hype and reality of the city’s always-just-over-the-horizon comeback.A map accompanying the article is labeled “A Sprawling City: Detroit’s downtown is compact, but the city is enormous, encompassing 139 square miles” (emphasis supplied).

As it turns out, 139 square miles is not at all enormous in the context of American cities. In fact, Detroit is a bit of a runt among its peers. Of the 20 most populous US cities, Detroit ranks only 18 in land area—just barely edging out Philadelphia (134 square miles), but comfortably beating San Francisco (47 square miles).

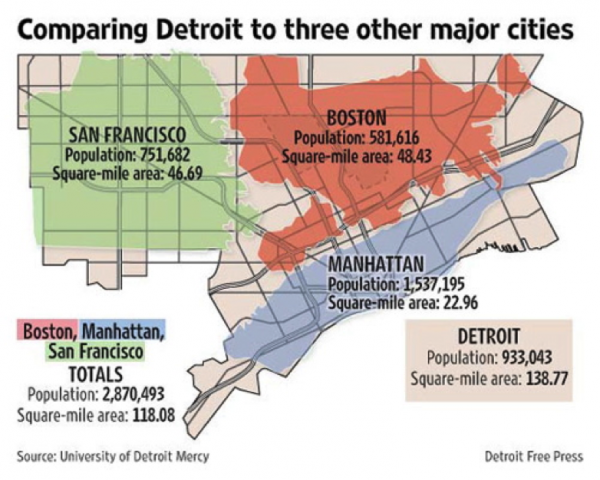

The most amusing “example” of Detroit’s vastness is that Boston, Manhattan, and San Francisco (or some other combination of small cities/parts of cities) can fit within its borders. This factoid is trotted out over, and over, and over, and over, and over, and over, and over, and over, and over again.

Source: MarkMaynard.com

These kinds of maps and comparisons are always fun to look at, and are certainly interesting to think about – but one lesson we should definitely not take away from this image is that Detroit is an uncharacteristically large American city. Unfortunately, the reverse is true. San Francisco, Boston, and Manhattan (and the Bronx, Minneapolis, and Miami—other places that are used to show how massive Detroit is) are uncharacteristically small and dense for American urban places.

This matters because size is frequently referenced as one of the city’s chief challenges. Such references typically precede discussions about “right sizing”—the city’s (never realized) plans to force residents to move to denser neighborhoods so services can be provided in a more cost-effective manner.

These conversations obscure the real issues at play. While it has been difficult for the city to provide services to all its residents, and it has surely been frustrating to deliver services to largely abandoned neighborhoods (of which there are many), to suggest that Detroit’s enormity is a key driver of the current crisis is misguided. For context, Austin, Texas (320 square miles) is more than twice the physical size of Detroit and yet is only 30 percent more populous. Providing basic services is not a problem for Austin. Denver, Colorado is a little larger than Detroit (153 square miles) and has nearly 40,000 fewer residents. Providing basic services is not a problem for Denver.

Detroit’s inability to provide basic services (functioning street lights, police, garbage collection, affordable water) to its citizens across its 139 square miles has less to do with the size of the city, and more to do with the lack of resources that results from the isolation of a remarkable concentration of metropolitan poverty. Detroit’s real problem is not that the city is sprawling, it is that the region is both sprawling and segregated by race and income.

Segregation, Suburbanization, and Detroit’s Ongoing Crisis

Throughout American metropolises, the rich, middle class, and poor are often segregated in different municipalities. Yet cities still rely on local revenues to fund many crucial local services. The result is that geography is often destiny for Americans. Those in poor cities have access to poor services, those in middle-income towns have access to decent services, and those in wealthy towns have access to excellent services. The Detroit metropolitan region, for example, contains 130 municipalities that are heavily segregated by income. Regrettably, even as Michigan’s overall tax burden has fallen (as a percentage of income and relative to other states), Michigan municipalities’ reliance on local sources of revenue has grown.

The Real Sprawl Problem: Metropolitan Detroit’s 3.8 Million People are Spread Across 130 Municipalities Covering 1900 Square Miles

Source: UrbanPlanet.org

A city simply cannot function as an isolated concentration of regional poverty. Yet this has been Detroit’s fate for decades. Even worse, Detroit continues to hemorrhage residents (most appear to be heading for the suburbs). Those left behind are, on average, poorer than those that leave. As a result, city services descend into a spiral of degradation and debt, even as tax rates increase. Detroit’s $18 billion dollar debt crisis is not merely the result of gross mismanagement, but the necessary result of a desperate municipality trying to provide its vulnerable citizens even the most basic services.

For example, the water department holds nearly a third of Detroit’s $18 billion debt. To help alleviate this, the city recently shut off water services for thousands of Detroit residents that have fallen behind on their water bills. Many have been unable to pay to have service resumed. The Detroit water department, supported by the city’s unelected and virtually all-powerful emergency manager, says that this draconian move is necessary in order to force delinquent residents to pay. But Detroit’s impoverished residents face some of thehighest water costs in the country. These costs have risen because the water department has had to spread costs across fewer and poorer residents, and turn to debt to fund basic maintenance of the system due to the city’s lack of tax revenue.

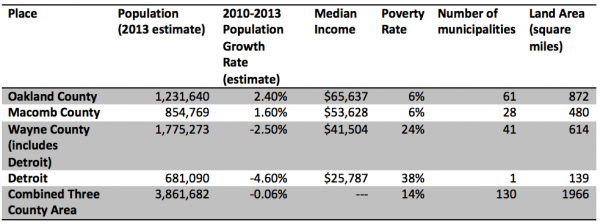

Resources Beyond Reach: Basic Population, Income, and Geographic Data on Detroit and The Surrounding Region

Source: Census Bureau American Community Survey

Many of our most vulnerable residents live in isolated communities like Detroit, but the way we fund basic services largely shields the rest of us from having to help them. Oakland County, Macomb County, and the areas of Wayne County outside of Detroit are quite wealthy, relative to the city (see above). Yet these residents are largely shielded from having to contribute their tax dollars to the struggling city (and other pockets of isolated poverty throughout the region). If we ever want to alleviate the crises of Detroit and similar communities, then we must increase the redistribution of wealth from suburbs to central cities.

Michigan to its Cities: Drop Dead

The unfortunate political reality is that greater contributions and cooperation are unlikely. Rather than pulling together to provide relief for Michigan’s most disadvantaged cities, the state decided to usurp local authority without providing any meaningful resources in return. In 2012, Michigan’s Republican-controlled legislature and executive worked together to pass “The Local Financial Stability and Choice Act,” a set of emergency laws that allow the governor to elevate “emergency managers” over local authorities. Such managers have virtually complete control over struggling cities and are tasked with enforcing austerity. As a result, struggling municipalities (Pontiac, Benton Harbor, Ecorse, Detroit, Inkster, Allen Park, Flint, and Hamtramck) sit helpless as already miserly services are cut further.

Yes, these cities were facing unsustainable debt, but not because of profligate governments. Without stable sources of funding, these cities had no choice but to turn to debt. Unfortunately, Michigan has cut its set asides for municipalities by about a third, a loss of more than $300 million for the state’s struggling cities. Such cuts will likely remain in place even as the state’s coffers recover from the recession. When faced with a potential $1 billion surplus, the state announced its desire to return most of this money through broad-based income tax cuts rather than to provide relief to its struggling municipal governments.

Source: Detroit 2013-2014 Budget

It will not be easy to make the case to suburbanites that they should take on a higher tax burden to support a city that, from the outside, appears mismanaged. But a case can and should be made that metro Detroit’s suburban residents have a moral obligation to the central city. Austerity and bankruptcy alone will not stabilize the city’s finances, much less bring about an economic recovery. The city’s remaining residents are simply too poor to afford basic services and therefore must turn to debt or simply do without. Before suburbanization, wealthy and middle-class residents subsidized impoverished Detroiters’ access to basic services like public safety, the fire department, water infrastructure, education, and transportation. Today, the political boundaries of the suburbs allow our wealthy and middle class residents to abdicate their responsibility to the region’s isolated poor.

If Detroit were truly enormous, and its boundaries extended to cover its metropolitan population, then the city could escape its death spiral and vastly improve its services while lowering its tax rates. While regional unification may not be in the cards, the least our affluent and middle class suburbs could do is pay a little more in terms of income or sales tax (or to share some of their property taxes) to help provide a streetlight or two. Better yet if we all lived closer together. In that case, we would have to pay for far fewer streetlights.

Chad Hughes is senior research analyst at Gartner Research Board. He studied economics and public policy at the University of Chicago and now lives in New York.

Detroit is 142.87 sq miles,,. We actually have a six county metropolitan area, Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Monroe, Washtenaw, and Livingston. Detroit is the oldest city east of seaboardccolonies, Detroit was incorporated as a city on September 13, 1806, Michigan didn’t become a state until January 26, 1837. Other cities were lucky because their surrounding areas didn’t become legal cities the way Detroit’s did. Our metropolitan areas is one of the oldest in the nation! And a little known fact about Wayne county, it’s borders once encompassed just about all of the state and even extended all the way to Illinois where Chicago is!

Detroit is 142.87 sq miles,,. We actually have a six county metropolitan area, Wayne, Oakland, Macomb, Monroe, Washtenaw, and Livingston. Detroit is the oldest city east of seaboard colonies, Detroit was incorporated as a city on September 13, 1806, Michigan didn’t become a state until January 26, 1837. Other cities were lucky because their surrounding areas didn’t become legal cities the way Detroit’s did. Our metropolitan areas is one of the oldest in the nation! And a little known fact about Wayne county, it’s borders once encompassed just about all of the state and even extended all the way to Illinois where Chicago is!

Poor analysis here by the author who should research the reasons why hundreds of thousands of people fled Detroit. Massive corruption, crime and horrible schools. Also, protectionist policies as the numerous articles comparing Houston to Detroit have laid out. So, authors solution is to expand the reach of the very poison (government) that caused the problem. Very typical. Wondering why people constantly refuse to accept that freedom is the cure for any problems created by freedom but government is not the cure for problems created by government.

Hey Robert, suck a dick.