By James Habyarimana and William Jack

A recent spate of horrific road crashes has brought the dangers of the developing world’s roads to light. A recent bus crash in western Kenya killed all 41 people on board, and 51 perished when a bus went off a cliff in Peru. Global statistics corroborate these accounts: 1.3 million people die on the roads each year, and amongst 15-29 year olds, road injuries are responsible for more deaths than any other cause.

Possible solutions include better roads and vehicles, high-tech medical services, and driver training and licensing, and it is right that we should aspire to live in a world in which these services are available to all. Such aspirations are consistent with the long-term economic and human development goals of most countries. But they will take time—a long time—to achieve.

In the short term however, we propose a proven, cheap, effective, and sustainable method to immediately tackle the global health epidemic of road deaths.

We have approached the problem of road safety from our perspective as economists. Why do so many buses crash in Africa and the rest of the developing world? The local manager of a bus fleet in the foothills of Mt. Kenya had the answer: driver behavior. As she told one of us, “Professor Billy, it is always the driver’s fault. Remember, he always has the option to slow down.” Local stakeholders understand that behavior change is the bedrock of improved road safety.

Speed limits and other regulations can help, but all too often the police appear to be unable, or unwilling, to enforce them. For example in Kenya draconian rules were introduced in 2004 to improve the safety of the country’s notorious matatus—14-seater minibuses that ply routes long and short across the country. A new piece of technology, a “speed governor,” that would automatically shut off a speeding vehicle’s engine, showed special promise.

However, while the regulations were widely believed to have reduced matatu malfeasance, our statistical analysis in fact shows they had precisely zero impact on road safety—any short-term reduction in crashes occurred because much of the matatu fleet was off the road, having their speed governors installed. Very soon, speed governors were disabled by drivers and accident rates returned to normal.

Are matatu drivers crazy? Face-to-face they are no different from other working Kenyans, but somehow these rational Dr. Jekylls, when put behind the wheel, are transformed into Formula 1-wannabe Mr. Hydes, high on khat or other stimulants to keep themselves alert, or at least awake. But stiff regulations to curb their behavior have gone unheeded and unenforced.

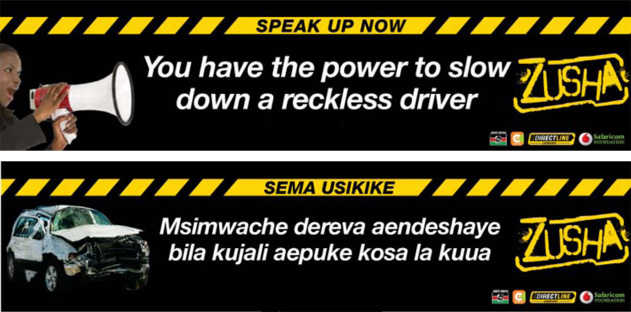

So instead of designing new gadgets and giving the police new powers, we appealed directly to passengers to monitor and govern the behavior of matatu drivers. The passengers were not asked to call a number, to send a text or a tweet, or to post a Facebook update. All of these responses are too slow to stop your driver from heading off a cliff. No, we simply empowered the passengers, gave them a voice, to complain directly—to “Heckle and Chide!”

To this end, we posted motivational messages encouraging riders to complain, complete with gory images of accident victims, inside matatus, and within easy view of the passengers. It was not pretty stuff, but we hoped the messages would legitimize complaints, and help riders coordinate their actions instead of each waiting for another to take a stand. Out of a total of about 2,500 vehicles, half—those with license plates ending in an odd number—were offered the stickers. The others served as a control group. This approach allowed us to cleanly and precisely measure the impact of the messages, by comparing the insurance claims of the two groups both before and after the intervention.

The results were astounding: vehicles offered the stickers were half as likely to make an insurance claim, and 60 percent less likely to have an accident causing injury or death. Amongst the 85 percent of vehicles that voluntarily accepted the stickers (compliance was optional), we saw even larger reductions in accidents.

These results were surely too good to be true, so we worked with an insurance company to repeat the exercise, this time with access to all 12,000 of its covered vehicles. The outcome was again spectacular.

And cheap. By our back-of-the-envelope calculations, the cost-effectiveness of the intervention at least matches the very best buys in public health, being cheaper than immunizations, improved maternal care, TB treatment, and others…and way, way, cheaper than building new roads and equipping hospital emergency wards.

We believe there is a strong argument for well-designed foreign assistance to combat deep problems of development, and roads and hospitals may well figure prominently in these efforts. But let’s also be willing to pick any low-hanging fruit we can find—let’s heckle and chide.

James Habyarimana is an Associate Professor in the McCourt School of Public Policy, and William Jack is Associate Professor of Economics, both at Georgetown University. They are co-founders and co-directors of gui2de, the Georgetown University Initiative on Innovation, Development and Evaluation.

Established in 1995, the Georgetown Public Policy Review is the McCourt School of Public Policy’s nonpartisan, graduate student-run publication. Our mission is to provide an outlet for innovative new thinkers and established policymakers to offer perspectives on the politics and policies that shape our nation and our world.

2 thoughts on “Heckle and Chide: Saving Lives on Africa’s Roads”

Comments are closed.