By Kai Filipczak

1983 was a year of soul-searching for educators. Following the release of the landmark report “A Nation at Risk,” the United States was confronted with the bitter realization that all was not well with its much-vaunted public education system. For years, civil rights activists had focused on the need to deliver education equitably, but the report helped identify a new problem: public education was (and still is) frequently mediocre, even for middle-class suburban students. For example, Montgomery County, MD is one of the most affluent counties in the United States, but its public school district barely performs at the 50th percentile in an international comparison of math ability.

Although many reforms have been implemented to make public education both more equitable and of higher quality, one of the most politically successful and bipartisan solutions has been the creation of charter schools. These schools are publicly funded based on enrollment, and gain increased operational flexibility in exchange for strict accountability of student outcomes. Since the first charter school, City Academy High School, was founded in St. Paul, MN in 1992, debate has raged over whether charter schools actually perform better than traditional public schools (TPS). This debate is often quite technical, and methodological criticism is very common. This is not an instance of mere academic quibbling; different research methodologies often paint very different pictures of charter school performance.

Selection bias has bedeviled charter school researchers since the first studies on student performance emerged in the mid-1990s. Fundamentally, the selection bias issue centers on how to reasonably compare the performance of students in traditional public schools and charter schools given that families make an affirmative choice to pursue an education at a charter school. The worry is that some difficult-to-quantify variable could be acting on families and students prior to or during their time in the charter school that would make the group of charter students different from TPS students. For example, it is plausible that families who choose to send their children to charter schools could have more books in their home, or are more likely to stress the importance of education as a means of self-improvement. Any one of these situations would create a selection bias problem. In fact, much of the methodological debate in charter school research discusses various methods of controlling for selection bias. Consequently, many critics of charter schools insist that increased student performance compared to TPS is an econometric illusion – the result of selection bias and subtle sorting of students that have not been adequately controlled for.

In addition to these long-term distal sources of selection bias, it is also possible that charter schools are actively “creaming” students through abuse of disciplinary policies. According to some public education advocates, charter school administrators target troublesome, learning-disabled, or otherwise low-performing students and suspend or expel them disproportionately in order to improve their school’s aggregate test scores. While this may be unintentional and simply the result of low performance and other factors being correlated, some critics take a more cynical stance and see active manipulation. If manipulation of disciplinary systems were found to be a major reason for increased charter school performance, this would conveniently undermine the legitimacy of the operational freedom that charter schools enjoy on matters such as discipline

A recent Washington Post article examined charter school expulsions in the District of Columbia. DC Public Schools adopted a uniform discipline policy in 2009 that permits expulsion only for severe violations, such as bringing a gun or drugs to school or assaulting students or staff, but charter schools may set their own policies. Of the approximately 76,700 students enrolled in DC Public Schools in 2011, about 29,300 attended charter schools. Despite only enrolling 38% of DC students, charter schools expelled 676 students between 2009-2011, compared to 24 expulsions in public schools. This gross discrepancy is highly suggestive at first glance, but it is possible that DC charter schools both discipline more students and earn higher test scores independent of this fact. Unfortunately, the Post article uses a blunt cross-sectional comparison that does not allow us to test this hypothesis. However, we can use student achievement data to see whether the test score advantage that DC charter schools have over TPS is larger than the possible gain that could come from disciplining only poor-performing students.

Data and Methodology

I used two sources of data in this analysis. I obtained information on charter school disciplinary rates from school years 2009-2010 to 2011-2012 from the District of Columbia Public Charter School Board. Specifically, I was interested in two measures of discipline: the number of students expelled per year and the number of students on long-term suspension (greater than 10 days). This data is publicly available and can be accessed here. I combined this information with performance data on the DC Comprehensive Assessment System (CAS) from charter schools and public schools. This data is maintained by the DC Office of the State Superintendent of Instruction, and can be accessed here. My analysis uses data from 189 schools in DC, and tests the sensitivity of charter school proficiency rates using more than 160 discipline incidents of each type over 3 years.

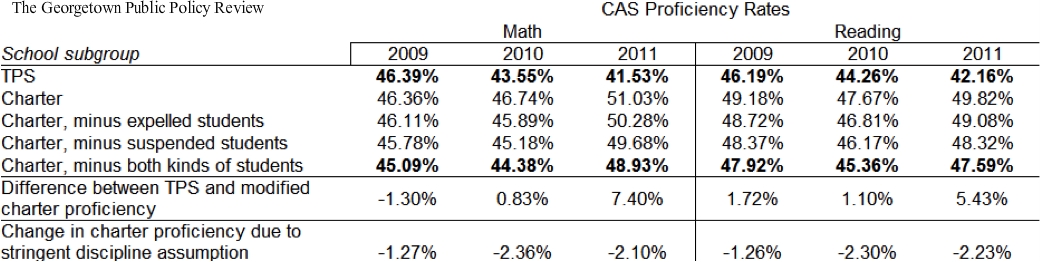

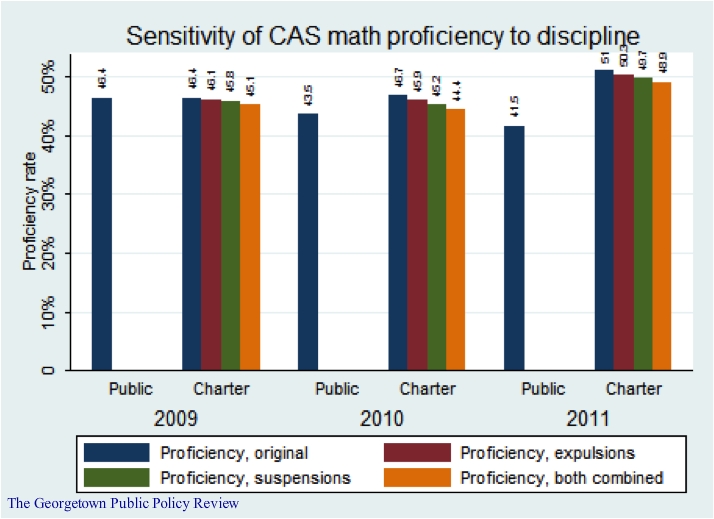

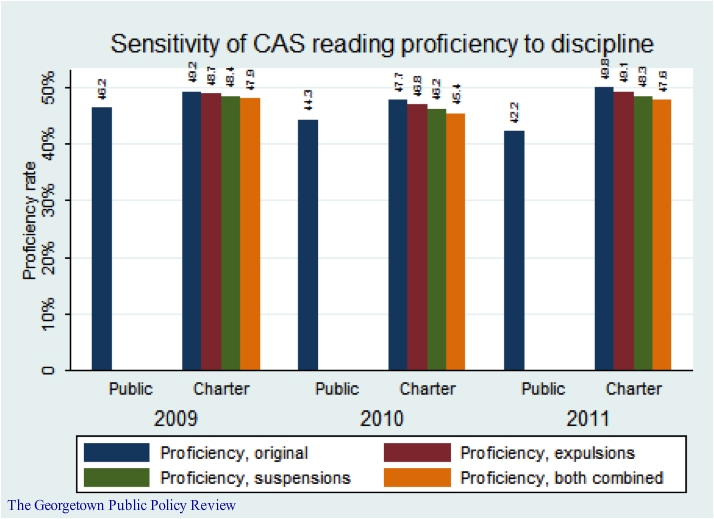

I use a simple and intuitive methodology to test the claim that the differences in math and reading proficiency between DC’s traditional public schools and its charter schools are due to differences in disciplinary policies. I begin with the average reading and math proficiency rates for public schools in each year. My data show that charter school proficiency rates are typically several percentile points higher than public schools. Essentially, I assume the strongest possible case against charter schools: that all suspended and expelled students would not have been proficient, and thus would have negatively affected the school’s proficiency rate if their scores had been included. I then generate a modified proficiency rate by subtracting the number of disciplined charter school students from the number of proficient students.

In fact, I generate three separate proficiency rates: one assuming that only expelled students would not be proficient, one assuming that only suspended students would not proficient, and one assuming that both kinds of students would not be proficient. By combining suspended and expelled students together, I also make the strong assumption that each disciplinary incident is discrete, with no student committing more than one offense. Furthermore, my procedure assumes that all suspended and expelled students were enrolled in grades that were subject to CAS testing. DC students are tested in math and reading in grades 3-8 and grade 10. These assumptions maximize the possible change in proficiency after assuming that disciplined students would not be proficient.

If the modified charter proficiency rates are still higher than public school proficiency rates even after granting these stringent assumptions, then disciplinary differences alone cannot be the sole reason for why charter schools show improved performance. A more plausible explanation is that greater charter proficiency rates truly reflect greater impact upon student performance rather than administrative abuse. . If, as mentioned above, charter school students have more books in their home or are raised in families that value education more, some student-level selection bias may yet occur. However, decreasing the proficiency rate mitigates the effect of yearly changes in the number of disciplined students at the school level.

My analysis assumes that charter schools that abuse the disciplinary process in order to improve school-level performance will expel low-performing students or put them on long-term suspension. This may not in fact be the case for some proportion of offending charter schools, as other methods might be used to hide poorly performing students from scrutiny. For example, a charter school might encourage underperforming students to transfer back to DC Public Schools, and this school-level effect would not be captured by my data.

Results

Charter schools retained their advantage over public schools in every year and subject where charter school performance was initially greater than TPS performance. DC’s traditional public schools outperformed charter schools in math proficiency in 2009, and so artificially lowering the charter school proficiency rate further widened the gap between the two kinds of schools instead of narrowing it. Even after artificially lowering the proficiency rate, DC charter schools are still 2.47 percentile points more proficient in math and 2.65 points more proficient in reading on average. 50% of DC charter schools had greater modified proficiency rates than the TPS average in math, and 47% of charters had greater modified proficiency in reading. Furthermore, the actual change in proficiency rates as a result of making stringent disciplinary assumptions was small in absolute terms: at most, the charter school proficiency rate changed by about 2.4 percentile points. While some individual schools expelled many students (for example, one school expelled 68 students in a single year), 37% of charter schools went an entire school year without expelling any students.

There is clearly much variation in implementation of disciplinary policies among charter schools, and so it is grossly unfair to assume that most charter schools have pronounced issues with discipline. Based on the results of my analysis, it is more reasonable to conclude that a handful of charter schools have questionable practices that deserve further scrutiny, but that the performance of DC’s charter schools as a whole cannot be simply due to disciplinary policies. Selection bias is still a pertinent issue for comparative effectiveness of TPS and charter schools, but there is little evidence that DC’s charter schools expel students or put them on long-term suspension in order to improve proficiency.

Other districts face similar questions of administration. Chicago Public Schools recently revised its discipline code to lessen the use of “punitive” disciplinary policies like automatic suspension and expulsion. Schools operated by the Noble Street Charter Network have been heavily criticized by Chicago activists for high rates of expulsions, as well as for unusual discipline practices, such as fining students for infractions. Charter schools in other districts may indeed be expelling a disproportionately large number of students, but my results should encourage critics of charter schools to be open to the possibility that these schools may also have high performance independently of this fact. Further research is necessary to examine discipline and proficiency in other districts and policy environments, and Chicago Public Schools would be an excellent subject.

In the meantime, it is reckless and unfair to insist that charter schools typically increase achievement through manipulation of discipline policies. The aim of education is to impart knowledge and a variety of skills, and honest reformers should not be wedded to geographically-assigned public schools and their traditions as a means of delivering this content. Is it really so hard to believe that alternatives to traditional public education can achieve stellar results without gaming the system?

Kai Filipczak is a recent graduate of the Georgetown Public Policy Institute (’13), where his thesis research examined charter school curricula, programming, and discipline policies in Michigan. He is currently working as a research associate at the Center for Education Reform.

Established in 1995, the Georgetown Public Policy Review is the McCourt School of Public Policy’s nonpartisan, graduate student-run publication. Our mission is to provide an outlet for innovative new thinkers and established policymakers to offer perspectives on the politics and policies that shape our nation and our world.

I think your note here is perhaps the most accurate picture of student transfers within D.C. from this article:

“”For example, a charter school might encourage underperforming students to transfer back to DC Public Schools, and this school-level effect would not be captured by my data””.

I’m not accusing Charters in D.C. of “encouraging” students to remain at DCPS once they leave, but I do believe that once students have been expelled from a Charter in the district, it is much more likely for them to remain at a DCPS school than to move onto another Charter, which would indeed offset your data – not that I think it would ultimately change your findings.

In the end, I think this piece runs past the debate and policy change DC needs most: When will OSSE step up its leadership role in setting standardized discipline standards for Charters in this city?