In 2009, the non-profit education reform organization TNTP (formerly The New Teacher Project) published The Widget Effect: Our National Failure to Acknowledge and Act Upon Teacher Effectiveness. This report spurred the redesign of many state and district teacher evaluation systems to more rigorously assess and address teacher effectiveness.

Last week, the New York Times printed a preliminary assessment of the impact of these revamped systems. The result? After investing millions of dollars in data systems, training, and testing, the new evaluations identify roughly the same number of poor performers—one to three percent—as the old evaluations.

Reformers cite the vagaries of test score cuts and evaluation norms as reasons why more ineffective teachers were not identified, but the overall trend of these new systems requires a deeper explanation. Evaluation systems still treat teachers like widgets—interchangeable in effectiveness—despite the fact that studies have shown individual teachers can have a significant impact on the academic trajectories of their students. Evaluation systems will fail to adequately recognize differences between teachers until we address the underlying issue of teacher hiring risk and turnover in high-need districts.

The Persistence of Evaluation Inflation

Leniency bias, the “Lake Wobegon” effect where all employees are above average, is not unique to the teaching profession. Studies have shown that, in private companies with five tiers of performance ratings, it is common to see 60 to 70 percent of employees in the top two tiers. It is standard practice across most US industries to rate most employees as above average. Those who push for accountability would like to identify five to ten percent of teachers as poor performers, yet they would be hard-pressed to find any American company that approaches these numbers.

The structure of a school creates even more incentives for supervisors to consistently rate teachers highly. Experts at Carnegie Mellon University have found that the more uncertain the indicators for performance, the more likely that supervisors will exhibit leniency bias in rating the employee. Principals face a number of uncertainties in evaluating teachers, including a lack of familiarity with course content, low number of classroom observations, and lack of contemporaneous student achievement data. This high level of uncertainty makes it more likely that they will issue a lenient appraisal.

Further, University of Cologne economist Dirk Sliwka finds that a fixed wage is a credible signal of trust in an employee, while pay-for-performance schemes reduce trust in favor of control. As the instructional leader of their classrooms, teachers require a high level of trust from their principal to perform their jobs effectively. Principals that find and address differences in their employees’ performance—through carrots or sticks—risk breaking trust with teachers and creating a negative feedback loop that could reduce the teacher’s effectiveness in her classroom.

The Real Widget Effect

The foundational argument surrounding the teacher evaluation reform is that old accountability systems prevented administrators from identifying teachers that they knew were underperforming. Therefore, the “true” Widget Effect occurs when nearly all teachers receive the same formal evaluation yet are informally regarded at different levels of effectiveness by their administrators. In this case, a real gap between employee performance and institutional assessment exists.

Using data from the TNTP report, we can see that the “true” Widget Effect seems to vary directly with the size of the district (Figure 1). Despite variation in principal dissatisfaction, the percent of instructors formally identified as unsatisfactory (and are therefore at risk of being dismissed) remains relatively consistent across district size.

Alternate Cause of the Widget Effect: A Hiring Risk Argument

In a previous report, TNTP showed how large urban district hiring practices inadvertently winnow out the highest-quality, highest-need teacher candidates. Late hiring schedules, union transfer requirements, and uncertain budgets prevent large school districts from hiring the most promising teachers.

From this information, it seems clear that the risk of a new hire being a “lemon” increases with the size of the school district. Consequentially, we could expect that principals in large districts might be less likely than those in small districts to fire teachers they perceive as ineffective. In a sense, it is worth holding on to “the devil you know” rather than risk investing the time and energy in finding a candidate that might be as ineffective or worse.

Many have argued that union and tenure restrictions are forcing principals to keep teachers they would have otherwise fired. Yet, even when given the opportunity to fire teachers, principals in large districts tend to keep the instructors they have rather than re-enter the hiring process. In 2004, Chicago Public Schools initiated a new procedure where probationary teachers could be dismissed with relative ease. A National Bureau of Economic Research study of the effects of this change showed that principals dismissed some teachers based on performance factors. However, a significant number of principals (roughly 30 to 40 percent) did not dismiss any teachers over a three-year time period. The study concludes that reluctance to fire poor performers “may indicate that issues such as teacher supply and/or social norms governing employment relations are more important factors than policymakers have realized.”

In the hopes of growing the supply of teacher candidates, large and rural districts have lowered barriers to entry by creating provisional certification and training programs. Linda Darling-Hammond argues that this strategy only exacerbates the teacher supply problem by increasing staff turnover and making the hiring process even riskier. Sixty percent of individuals who enter teaching through provisional certification programs leave teaching by their third year, compared to 30 percent of teachers with traditional training. The education sector is already far more susceptible to turnover than other professions, and districts with the highest need often face the highest churn rate.

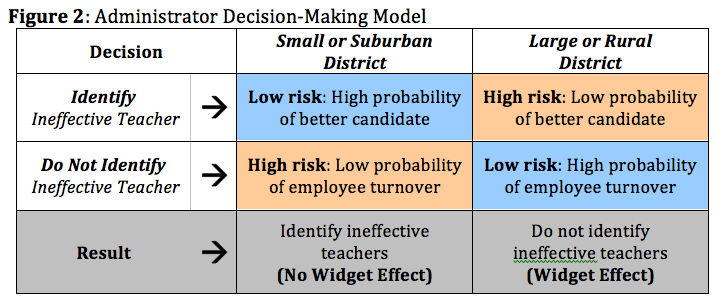

Districts with poor teacher supply and higher turnover—typically large urban districts and small rural districts—have a double-barreled reason not to identify poor performers under any evaluation system. There’s a high risk that the effectiveness of new teachers will not justify the time and money spent on the hiring process, and there is a high probability that an ineffective teacher will leave voluntarily due to pervasive turnover (Figure 2).

Many education reformers have pinned their hopes on using new evaluation systems to identify poor performers. As the effects of these new policies continue to play out, we must look past the idiosyncrasies of individual evaluation systems and acknowledge the path we’ve chosen: one that focuses on removing teachers deemed ineffective without building up a deep and stable supply of effective teachers to replace them.

Kristin Blagg is a student in the Master of Public Policy program with a focus in domestic social and economic policy. She has interned at Education Policy Program of the New America Foundation, in the Tennessee Department of Education, and in the office of former Representative John Olver (D-MA). Kristin spent four years as a math and science teacher prior to entering graduate school. She has a M.S. in Education from the Teacher U program at Hunter College and an A.B. in government from Harvard University.