By Manon Scales

As we continue to slog through this highly irregular and seemingly deadlocked budget season, the nebulous “reduction of tax expenditures” is a frequently discussed strategy for addressing the deficit. Despite its recurrence in many sound bytes and its mention in both the House and Senate budget resolutions, no proposals for substantive action in pursuit of such a strategy have surfaced.

By far the largest tax expenditure is the employer-sponsored health insurance (ESI) subsidy. The primacy of employer-sponsored insurance in our current health system, coupled with its favorable tax treatment, is projected to cost the government approximately $760.4 billion in forgone tax revenue from 2013–2017. Such forgone revenue is projected to amount to 1.8% of GDP from 2013–2022. While the thought of making changes to the subsidy is anathema to most, a comprehensive consideration of the major provisions of the 2010 Affordable Care Act (ACA) suggests that there may be an opportunity to significantly alter or remove the current employer-sponsored insurance tax subsidy without sacrificing its most important beneficial effects.

Contrary to popular perceptions, the ESI subsidy benefits employees, not employers. Employers deduct employee compensation as a business expense regardless of whether it is paid in the form of wages or insurance coverage. Because insurance benefits provided to employees are not subject to tax (as opposed to wages, which are taxed at an individual’s marginal tax rate), a dollar paid to the employee in the form of health insurance is worth more relative to a dollar paid in the form of wages. Thus, the subsidy incentivizes employees to obtain health insurance when their employer offers it.

While the uptake of insurance coverage is certainly a positive outcome, especially as we work towards universal access to health insurance, opponents of this subsidy note that it is regressive in its implementation. Individuals with higher incomes—and thus higher marginal tax rates—benefit more from the deduction than those at lower marginal tax rates. Individuals with higher incomes avoid the relatively higher tax burden by receiving higher compensation in the form of insurance than lower income individuals.

Critics argue that the regressivity of the ESI subsidy serves to increase insurance and health disparities by incentivizing higher-income individuals to opt for increasingly generous and expensive insurance plans. For example, in order to have a dollar to spend post-taxation, an individual with a marginal tax rate of 35 percent must earn an additional $0.54 over that dollar. An additional dollar towards a new car, then, actually costs $1.54. An additional dollar of health insurance benefits, however, is paid with pre-tax income, so the employee pays $1 and receives the full value of the benefits for that dollar. The fact that higher-income employees can obtain increased insurance benefits at a cost significantly below that of other goods creates an incentive for these workers to opt for more generous and costly plans. Given the current fiscal environment and the specter of ever-increasing healthcare costs, it seems that federal dollars could be better spent in a way that avoids creating such incentives. Whether such funds go toward more targeted subsidies, bolstering another struggling federal program, or reducing the deficit, options abound for their arguably more constructive use.

If, as I think most would agree, the effects of the ESI subsidy are positive insofar as they increase employee access to and uptake of insurance, it makes sense to consider the possibility that more targeted alternatives may prove to be more efficient in doing so than the current exemption. The Affordable Care Act (ACA) provides an opportunity to implement such alternatives.

While the ACA focuses heavily on reforming the small group and the individual health insurance markets, it also utilizes a combination of mandates and incentives designed to increase employer offering and employee uptake of coverage. Employers with more than 50 employees will be required to offer affordable coverage to all full-time employees beginning in 2014. The Act incentivizes firms with 25 or fewer employees to provide coverage by offering tax credits for those that offer coverage and contribute at least 50 percent of the premium amount. Additionally, the individual mandate will take effect in 2014, requiring that most individuals purchase health insurance coverage. The need to satisfy this mandate will likely serve to maintain (or even increase) employee demand for ESI, and the employer mandate will further reduce any incentive employers currently offering insurance may have to stop offering it, even in the face of changes to its favorable tax treatment.

As previously suggested, employers are economically indifferent between paying their employees in wages and paying them in the form of health insurance. The employer mandate and small-business subsidies serve to sway this indifference such that more employers will offer coverage. This, along with the individual mandate supporting employee demand for such coverage, suggests that an alteration (such as a capped deductible amount) or elimination of the favorable tax treatment of ESI is unlikely to adversely affect the employer provision of insurance. In fact, its limiting or eliminating may decrease the incentive that exists for high-income, already insured employees to opt for increasingly expensive and generous plans because of their tax treatment.

It is important to note that any contraction of the ESI subsidy will make insurance relatively more expensive, as individuals will be paying their premium contributions with taxed dollars. Again, the ACA offers provisions that could address the affordability concerns inherent in a change to the ESI subsidy. Employees will be eligible to purchase insurance through one of the newly created exchanges if the insurance offered by their employer becomes unaffordable (a threshold currently set at 9.5 percent of income).

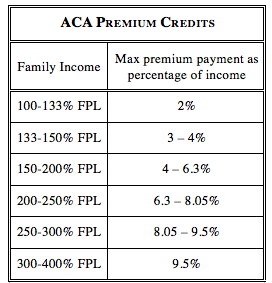

Additionally, families and individuals living between 100 and 400 percent of the federal poverty level who purchase insurance through an exchange will be eligible for refundable and advanceable tax credits to limit premium costs as a percentage of income. As such, employees for whom ESI might become unaffordable would be protected from the loss of insurance by the options introduced under the ACA.

The tax credits, many are quick to note, will not come cheap. The Congressional Budget Office estimates that exchange subsidies and related spending will cost $127 billion in FY 2022 and total $808 billion over the 11-year period from 2012–2022. This is expensive, certainly, but less so than the revenue that will be forgone because of the ESI subsidy over this same period ($760.4 billion from 2013–2017 alone). These numbers suggest that the repeal or modification of the subsidy has the potential to generate enough revenue to completely pay for the ACA subsidies, perhaps even generating a net increase in revenue. Such a scenario would represent a more nuanced targeting of funds: working to provide more individuals with health insurance while minimizing the incentive for over-insurance among wealthier individuals.

If we are serious about taking substantive steps to improve government efficiency and reduce the deficit, hard decisions will have to be made. Naturally, we should seek to make these decisions in ways that will minimize the negative impacts of reducing current spending levels. The ACA targets incentives toward increasing insurance where it is most lacking—among low-income and small business employees—and offers protection against unaffordability for these populations. When these provisions take effect in 2014, the ESI subsidy may become duplicative and function only to continue incentivizing increased health spending at higher income levels. As such, the implementation of the ACA may provide an opportunity to significantly alter or eliminate the ESI tax expenditure without negative impacts on insurance coverage, inequality, or costs. As we continue to pursue our health policy goals in a deficit-constrained environment, this often-dismissed policy option and its potential outcomes may warrant more serious consideration.

3 comments

This was a great read, though I have one issue with the conclusion. (Please feel free to check my math!)

“As previously suggested, employers are economically indifferent between paying their employees in wages and paying them in the form of health insurance.”

This is true only in a universe like our own, where an employer can provide, say, a $5600/yr insurance plan–and include the value of that plan in her total compensation–in lieu of paying her the $5600 to go buy the insurance herself. In this world, it doesn’t really cost the employer anything, so, meh, why not spring for covering her insurance?

But, if you take away the subsidy, even considering the incentives and the penalties imposed by ACA, it is no longer mathematically equal. (Unless you actually believe that salaries would rise dollar-for-dollar in companies that drop or curtail their health insurance offerings, which I believe the jury is still out on, but let’s make safer assumption here and assume they won’t.) The incentives and the penalties make it close, but not equal. For small employers, the gap may be only a couple hundred dollars–which is to say, it may be only a couple hundred dollars more expensive to provide employees’ health insurance than it would be to endure the 2016 penalties for failing to provide coverage, and at that point: make your employees happy, go the distance, and cover their insurance. It’s only a couple hundred dollars. So for small employers, the ACA structure is sufficient to get employers to behave the way we hope they will.

But for large employers, the gap is many orders of magnitude larger and it ceases to be a question of making employees happy and starts to become a major business decision. Because the penalty to an employer for having one of its employees receive an insurance premium subsidy is less than the cost of that employee’s insurance (and it is), removing the ESI subsidy makes it *considerably* cheaper to drop their employees’ coverage. Notably, the “individual mandate” penalty for an individual who lacks insurance is *also* less than the cost of a plan. If those working at large employers have their insurance coverage cut, some will by choice or by failure to act, not buy insurance, pay the penalty, and pocket the remainder as [taxable] income.

When the author here discuss the budgetary savings associated with ditching the ESI subsidy in lieu of the ACA incentive/penalty structure, it’s important to note that the savings does not come out of thin air–it only occurs because some employees will forgo insurance or will pay taxes on a portion of compensation where they currently don’t. Perhaps more impactful though, is the fact that if I am right and some large-employer workers are booted from the ESI market, the responsible majority of them who decide to buy insurance and who make less than 400% FPL will need to avail themselves of the exchange subsidies, thereby making the $808 billion cost estimate of that expenditure–which was calculated in the presence of the ESI subsidy–far too low.

Point being: ACA seems to cover a lot of the same ground as the ESI subsidy, sure, but that doesn’t necessarily mean we can save money and get the same results by ditching the subsidy.

[…] Read more on Georgetown Public Policy Review […]

[…] Read more on Georgetown Public Policy Review […]

Comments are closed.