Guest contributors Dev Chandra and Robert Reynolds explore why non-activist Democrats have trouble mobilizing their friends to vote. Through original qualitative and quantitative research, the authors use behavioral science to investigate this trend and address implications for Democratic strategy in the upcoming elections.

In 2018, Democrats piloted new methods aimed at sparking liberals to get their friends to vote. These “relational organizing” programs ranged from tweet reminders that mobilize friends to mobile phone apps that identify which contacts are irregular voters. Yet, something is missing from Democrats’ relational organizing know-how: No one can precisely explain why Democratic voters don’t get their friends to vote.

Democrats must identify the root causes that inhibit people from urging their friends to vote. Without this, they may invest in ineffective strategies. For instance, their methods may focus on increasing people’s motivation to nudge their friends, but if motivation was never the core problem, this would yield little benefit.

To inform the design of peer mobilization programs for non-activists, we completed a behavioral science-based analysis of the key barriers these Democrats face. We focused on non-activists (Democrats who vote, but don’t volunteer for campaigns) because they are the majority of Democratic voters, have stronger ties to irregular voters, and may be more effective messengers. Given these strengths, we believe behavioral science techniques that spark non-activists to mobilize friends are the frontier of Democratic voter turnout.

What impedes non-activist relational organizing

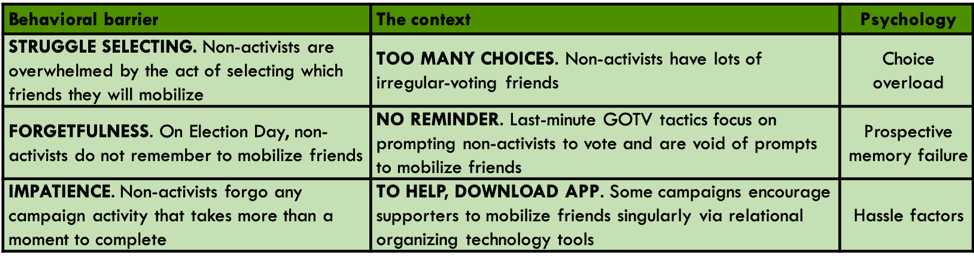

To diagnose the key behavioral barriers that impede non-activists, we polled a sample of 261 non-activist voters using the online Mechanical Turk survey platform and interviewed numerous behavioral scientists and political campaign professionals.* At this time, preliminary findings suggest there are three key barriers that prevent non-activists from mobilizing their peers: (i) struggle selecting friends, (ii) forgetfulness, and (iii) impatience.

One barrier inhibiting non-activists is the struggle selecting which friends to mobilize. The more options people can choose from, the more likely they are to avoid choosing. Behavioral scientists call this phenomenon “choice overload.” A prominent study on this topic finds that the more 401(k) plans employees can pick from, the less likely they are to choose a plan at all. When it comes to elections, people often have many politically like-minded friends. While activists may relish the abundant number of personal contacts they can mobilize, for non-activists the burden of choosing which specific friends to mobilize may induce enough choice overload to inhibit many from relational organizing.

A second barrier hindering non-activists is forgetfulness. When people aren’t cued to take action at the right moment, they forget to act. This is called “prospective memory failure.” One study on the ramifications of this found that neglecting to send students SMS reminders about financial aid deadlines strongly reduces community college re-enrollment rates. In 2018, Election Day videos from prominent campaigns — including Beto O’Rourke, Stacey Abrams, and Andrew Gillum — were void of reminders to mobilize friends and instead focused singularly on prompting the viewer to vote. Absent a cue to remind their friends to vote, non-activists who are not fiercely invested in the election might simply forget to nudge their friends.

A third barrier derailing non-activists is impatience. As a task’s difficulty increases, people become less likely to complete it. For example, a study finds that when college financial aid applications add steps, students become less likely to attend university. Unfortunately, the activation energy needed to download political or relational organizing apps exceeds what most non-activists will exert. That explains why less than 1 percent of Democrats downloaded Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign app. By definition, non-activists are disengaged, so programs that spark them to mobilize friends must be ultra-lightweight.

Implications for upcoming elections

If Democrats want to win in 2020 with relational organizing, they must get non-activists to mobilize their friends. However, with the looming 2020 presidential primaries and general election, no existing method accomplishes this at scale. Democrats need a technique simple enough to maintain impatient supporters’ attention and elegant enough to help them select which friends they’ll mobilize and remind them to take action on Election Day. If such a tactic can be invented and scaled in the next year, it may make all the difference in 2020.

* A comprehensive review of our findings and methods will be published in Dev Chandra’s master’s thesis in April 2019

—

Robert Reynolds is a behavioral scientist who designs researched-based, relational voter turnout techniques. He is Co-Founder of VoteTripling.org, a non-profit that advises political campaigns and voter turnout organizations, and a graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School.

Dev Chandra is a second-year MPP student at the Kennedy School and the careers chair at the Harvard Behavioral Insights Student Group. His master’s thesis investigates opportunities to use behavioral science to boost voter turnout.

Photo via Flickr / Ed Schipul

Dev Chandra is a second-year MPP student at the Kennedy School and the careers chair at the Harvard Behavioral Insights Student Group. His master’s thesis investigates opportunities to use behavioral science to boost voter turnout.

Robert Reynolds is a behavioral scientist who designs researched-based, relational voter turnout techniques. He is Co-Founder of VoteTripling.org, a non-profit that advises political campaigns and voter turnout organizations, and a graduate of the Harvard Kennedy School.