The Democratic base is angry at red-state Senators — Democrats elected in Republican-leaning states who sometimes cast crucial votes with the GOP. But Democratic activists shouldn’t count on radical reform if their party comes to power.

The battle over the confirmation of Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh was among the most divisive in recent memory. The Senate, split 51-49 in favor of the Republican Party, voted 50-48 to confirm Kavanaugh, with Sen. Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) voting present, Sen. Steve Daines (R-Mont.) not voting and Sen. Joe Manchin (D-W.Va.) joining the Republicans.

The count is somewhat deceptive in that Manchin was not, in fact, the deciding vote. He waited until Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine) confirmed her yes vote before siding with the Republicans. Assuming he was not genuinely torn and moved to action by Collins’ floor speech, it seems safe to say that Manchin simply jumped on an already-decided vote to bolster his conservative bona fides in deep-red West Virginia.

The gesture, however empty, stoked anger from left-leaning activists about both Manchin and the nature of the Senate: What is the point of having a Democrat who cannot or will not hold the party line? And should Democratic voters push to reform a system in which one legislative body puts the party at such a significant disadvantage?

In this article, I argue that while the Senate is — by design — not a truly democratic body, Democratic activists should not count on radical reform to deliver them a lasting supermajority. I note that as long as the current rules are in play, “red-state Democrats” will be a crucial component of any competitive progressive coalition. Finally, I conclude that there is a frustrating lack of evidence that votes like Manchin’s help Democrats keep their seats in otherwise conservative areas.

The Senate is not going anywhere

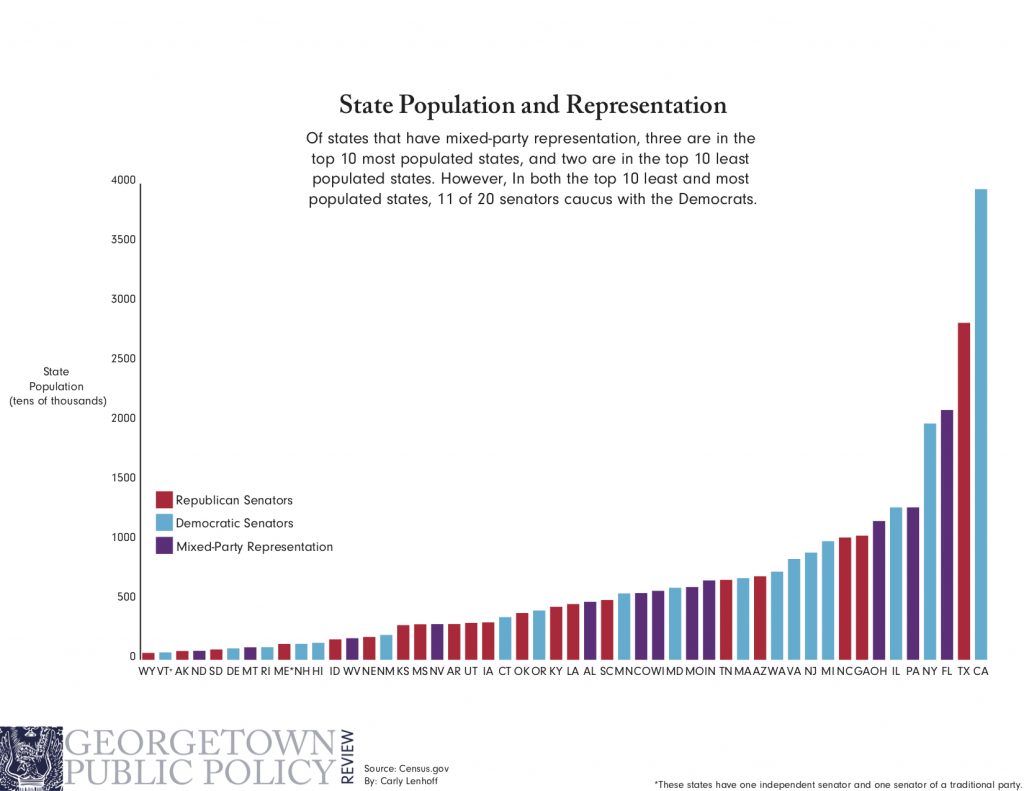

The Senate is an institution devised to limit the power of an overambitious majority. Designed as part of a compromise that would prevent highly populated states from exerting too much influence over federal policy, its structure now serves as a formidable obstacle between Democrats and a majority needed to enact meaningful policy changes, since a substantial portion of Democratic voters reside in a handful of populous states. Some activists and writers on the left advocate for the Senate’s abolition or reform, as the size discrepancy among states is more severe than ever.

Turning Congress into a purely proportional body would benefit the Democrats in the short term, simply by virtue of California’s existence. But the undemocratic structure of the Senate does not come without benefits for the Democrats.

In the 10 least populated states — that is, the ones that gain the most from equal state representation in the Senate — 11 of 20 Senators caucus with the Democrats. That is the same ratio as in the 10 most populated states. Things begin to skew more toward Republicans in the next-lowest quintile, but it is worth noting that many of the states with the most egregiously inflated representation elect Democratic Senators.

A look at population growth presents another concerning trend for liberals interested in Senate reform: The 10 slowest-growing states are home to 14 Democratic Senators; the 10 fastest-growing are home to only six. Some speculate that rapid population growth in states like Texas and Arizona brings with it demographic changes that favor Democrats. The Democrats’ polling in the South this cycle is its strongest in years, but a blue takeover remains far from guaranteed.

None of these concerns refute a political theory-based argument that the Senate should be more democratic. But in the long term, changing the structure of the Senate is not guaranteed to make it more Democratic.

If strategists on the left recognize this — which I expect they do — they will continue to find a way to win the Senate under the current rules. And even though many of the smallest states are reliably Democratic, that means a certain degree of reliance on figures like Manchin.

The importance of red-state Democrats

President Donald Trump won 30 states in the 2016 election. While his margins were minuscule across the Midwest and he lost the popular vote by nearly 3 million, the fact remains that voters in 30 states — the same voters who could represent a potential supermajority in the Senate — found enough common ground with Trump’s vitriolic 2016 campaign to deliver him their electoral votes. That is a hard circle to square for those who demand uniformity from the Democratic caucus.

Some argue that doubling down on progressive ideas might win back frustrated Democrats and independents who voted for Trump. Or perhaps a more cautious approach is justified: Red-state Democrats should campaign as moderate conservatives in a big-tent party opposed to right-wing extremism. Maybe both are true to different extents. In any case, securing a powerful Democratic majority in the Senate will require convincing some Trump voters.

In an era of increasing polarization and partisan sorting, the concept of self-identified Democrats who are accountable to Trump voters marks a fascinating juncture. When a Senator’s party leadership has made opposition to Trump’s every move its modus operandi while the Senator’s constituents approve of Trump by massive margins, how does a Senator vote?

Why do red-state Democrats cross party lines?

Red-state Democrats tend to have more latitude from the national party than other Democrats when it comes time for floor votes, as it is broadly accepted that conservative votes on certain issues are necessary to keep their constituents happy. Some areas make perfect sense: A more conservative record on gun control makes sense for a Democrat from an overwhelmingly rural state, for example, and a skeptical approach to energy regulation makes sense for one from an oil-producing state.

But some party-bucking votes do not follow a logic based on states’ economic needs or constituents’ immediate interests. It is hard to see how Manchin’s yes on the Kavanaugh confirmation — or Heidi Heitkamp’s (D-N.D.) and Joe Donnelly’s (D-Ind.) yeses on that of Justice Neil Gorsuch — serve their constituents in obvious ways. Even red-state Democrats have held center-left views for years on issues like executive power, healthcare, taxation and abortion rights. Kavanaugh is expected to make the court substantially more conservative on many of these matters.

These votes can be interpreted purely to show independence from the national party and cooperation with the Republicans. This raises an important question: Do Manchin et al. truly need to do this?

While Supreme Court votes are high-profile political events, there has been little research to suggest that red-state Democrats who refuse to support Republican judicial nominees face electoral consequences. The Democratic position has indeed weakened in some red-state Senate elections over the last few weeks. But it’s unclear if the Kavanaugh vote is to blame, and polling suggests that the vote actually mattered more to Democrats than to Republicans.

In 2018 — when “dark money” nonprofit groups can fund extensive attacks on the airwaves, or the president can instantaneously trash anyone in front of millions of followers on Twitter — Senators could be forgiven for playing it safe if they have the option of simply joining the winning side. But little about the modern Republican Party suggests that it would not throw its weight behind any credible challenger, no matter how many times a red-state Democrat has crossed party lines.

Conclusions

The undemocratic structure of the Senate, while generally disadvantageous to Democrats, secures several safe Democratic seats in small, low-growth states. Meanwhile, many of the fastest-growing states lean decidedly Republican. This makes it unlikely that Democratic leadership will challenge the fundamental structure of the Senate, even if it puts them at a current disadvantage.

Still, Trump’s victory in 60 percent of states means that red-state Democrats will continue to be a crucial piece of any secure Democratic coalition for the foreseeable future, unless or until Puerto Rico and Washington, D.C. gain statehood. These Democrats must navigate a difficult political landscape to maintain credibility at home while generally adhering to the national party platform.

More research is needed into these Democrats’ behavior, particularly on whether party-bucking votes do anything to improve their odds of reelection.

***

Photo via Flickr/Phil Roeder

Pat is a writer, editor and general communications professional from Montpelier, Vermont. He works for the university and is on his way to becoming a double Hoya ('14, '19). Pat hopes to use his degree to help improve policy literacy in political communications.