In 2014 technology research firm Gartner projected that one-third of global jobs will be replaced by robotics, software, or machine learning by 2025. While technological advancements have been shifting entire labor markets since the beginning of time, the rate at which Moore’s Law is increasingly blurring the lines between algorithmic computing and human decision making promises to make this era of automation far different than those that have come before.

As about half of all jobs in both the U.S. and OECD countries become automated over the next two decades, governments and firms across the world must adapt to a world where the human worker is increasingly unnecessary. From Nevada to Guangzhou, governments and corporations are constructing “zero labor factories” that fully automate the manufacturing of everything from cars, to consumer electronics, to clothing.

Previous eras of automation have involved liberating humans from manual labor (the sewing machine in the 18th century) or eliminating dull and unnecessary tasks (departing from switchboard operators in the 20th century). While those who lost out to technological advancements during those periods also participated in end-of-work fear mongering, they eventually had no choice but to accept a new world defined by different skill sets. The most recent era of automation taking place in the 21st Century is unique in that machines are encroaching on the decision-making capabilities previously thought to be confined to the inner workings of the inimitable human brain.

Many believe that machines will never be able to replicate the capacity for intimacy, compassion, and emotional response implicit in tasks like writing, painting, or acting. However, while C-3PO will not be replacing the likes of Philip Roth any time soon, there are already signs that AI programs may be able to develop the literary flourish or emotional understanding previously thought to be reserved for humans. In 2016, artificial intelligence programs constructed novels based on character and plot ideas provided by humans and made it past the first round of Japan’s Nikkei Hoshi Shinichi Literary Award competition. Computers are already being used for psychological therapy, with research showing patients may be more honest with a machine they know will not pass personal judgment. Companies like Google and Facebook have been successful at teaching AI machines to write poem collections and children’s books.

Technology is also outpacing the ability of human workers to train and educate for the novel skills needed in the industries affected by automation. MIT researchers Andrew McAfee and Erik Byniolfsson have labeled this trend the “great decoupling,” whereby employment is no longer rising in parallel with productivity. In economic terms, this means that the ratio of labor to capital is shifting heavily in favor of capital, creating significant diminishing marginal returns to labor.

Faced with this uncertain future, governments and companies must reinvent educational models to imbue global citizens with the non-cognitive skills and abilities needed to augment the intelligence revolution.

Refusing to Accept the Future

As automation continues at an unprecedented pace, many governments continue to cling to the past to avoid the sociopolitical repercussions that come with innovation. Instead of developing new educational models to train displaced workers for the skills of the future, many countries are instead subsidizing domestic industries that are being priced out by cheaper products made possible through automation. Other countries are refusing to take full advantage of automated solutions, instead choosing to bow to the demands of human workers opposed to robotic replacement.

There are also those that have accepted the fate of technological automation but have chosen to give up on closing the gap between productivity gains and employment growth. Policymakers in countries around the world have slowly started advocating for Universal Basic Income plans that would provide financial support to citizens to simply live with the disproportionate job loss associated with technological innovation. While there has been no full-fledged adoption of universal basic income in any country yet, the idea has received the support of top economists and politicians.

The Re-return of Soft Skills

To address the increasing rate of automation, educators are integrating coding and STEM skills into curriculums all the way down to the kindergarten level. The focus of education systems across the world has turned to transferring fixed computing and engineering knowledge to students, and testing the mastery of such concepts through standardized testing regimes.

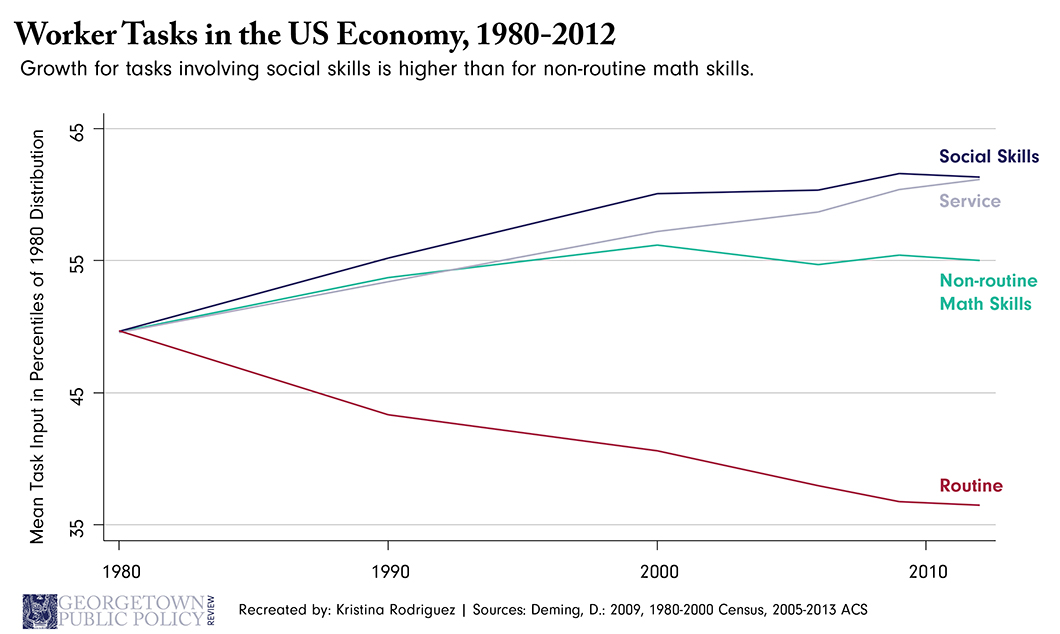

Automation is occurring so rapidly, however, that seemingly innovative STEM education programs may be irrelevant by the time students are ready to contribute to the global economy. In fact, research suggests this trend has already begun, with occupations utilizing non-routine mathematics skills growing only by 11% compared to 24% for those requiring social skills. Because adaptable social skills are ultimately what separate human workers from algorithmic machines, it is those positions requiring STEM knowledge with low levels of social interaction that will likely be automated over the next decade.

Instead of educating for the present, educational institutions must strive to prepare students for the future. To do so, governments, academic institutions, and private companies must change what they are teaching and how they are teaching it.

The Skills of the 21st Century

Automation displacing a significant portion of global employment does not mean we will soon prostrating ourselves to robot overlords. Instead, as advanced algorithms become ingrained into the fabric of every industry, there will be an increasing demand for skills that augment machine intelligence. Higher level “sense-making” skills represent those analytical components of the decision making process that are difficult to distill into an automated algorithm (for now). As technology increasingly takes over menial tasks, those learning to deftly apply soft skills will be better able to perform sophisticated tasks that leverage the strengths of human cognition.

So what skills should tomorrow’s workforce be learning?

In a report published earlier this year, the Global Markets Institute at Goldman Sachs stressed that “creativity, judgment, and social skills” will be critical to the “organizing, coordinating, and supervising” that will replace the “doing” now being done by technological automation. As the authors of the report admit, while routine tasks will become completely automated, humans still maintain a distinct comparative advantage in non-cognitive skill sets. It is those skill sets that best augment machine intelligence – problem solving, interpersonal interaction, consumer preference analysis, adaptive customization, team building, and social cue reading – that are most needed by the workforce of the future.

Aiming at a similar goal, a team of LinkedIn researchers in 2016 further defined 21st century skills by assessing what soft skills current employers labeled as most valuable when hiring candidates. Among the most in-demand skills cited by employers were communication, organization, teamwork, punctuality, critical thinking, social skills, creativity, interpersonal communications, adaptability, and friendly personality. Interestingly, it is the broad low-level soft skills like business planning and resume writing with greater potential for automation over the next two decades that were listed as being least in-demand.

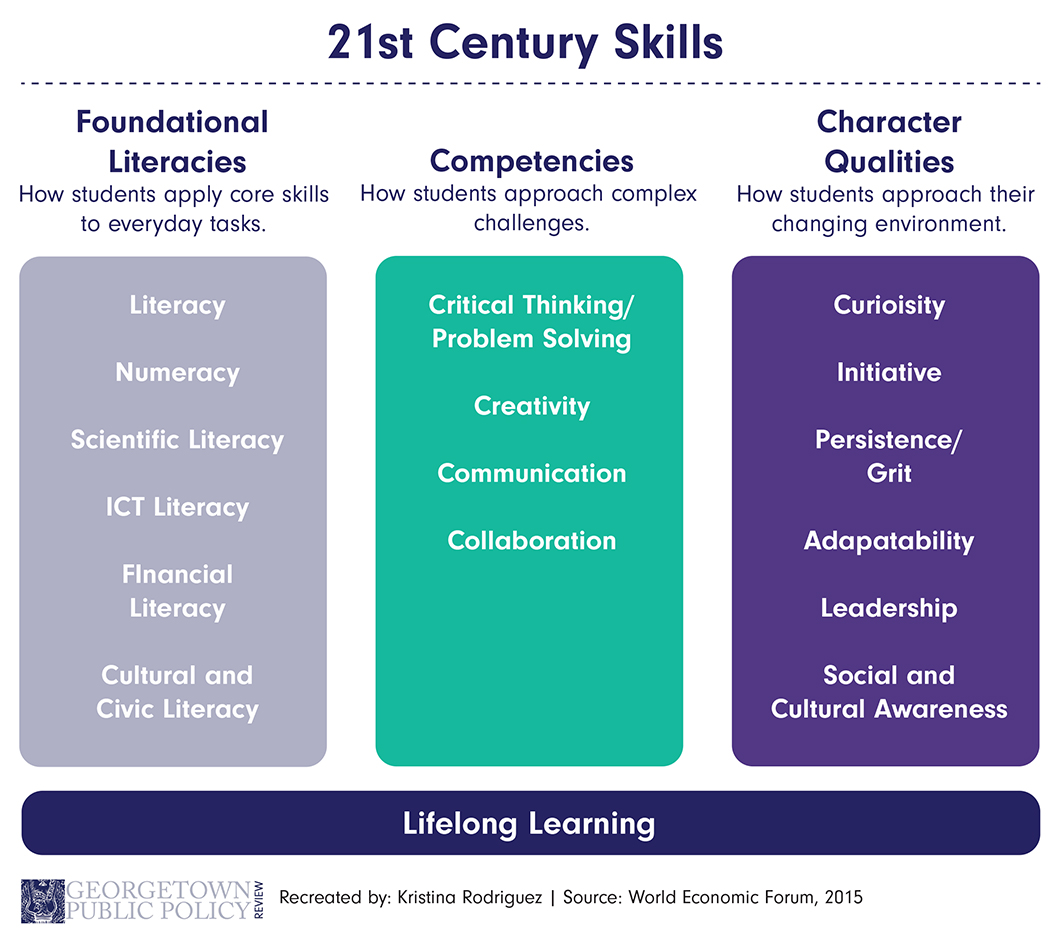

In 2015, the World Economic Forum and Boston Consulting Group also weighed in, conducting a meta-analysis of 21st century skills at the primary and secondary education levels to codify 16 skills distributed across three distinct categories.

Rather than eliminating traditional subject-based skillsets, the model situates skills like math, reading, chemistry, and geography underneath cross-disciplinary topics like financial, cultural and civic, and scientific literacy. By wrapping all three categories together under the model of lifelong learning, the practitioners and academics behind the report aim to show how the choice of pedagogy to teach foundational literacies should ultimately promote soft-skill competencies like collaboration and communication.

The Institute for the Future has also attempted to define workforce skills in the post-automation world, aggregating data trends and soliciting expert opinions to formulate a report on the “Ten Skills for the Future Workforce.” Several of the skills codified by the consortium of professional and academic participants – computational thinking, cognitive load management, and sense making – were directly related to leveraging soft skills to augment AI in order to produce product innovation. As automation brings STEM-focused analysts out of hiding from behind the shimmering computer screens of the modern workforce, the interpersonal skills highlighted by the report – social intelligence, cross-cultural competency, and virtual collaboration – will become even more important for turning data and automated processes into economic productivity.

A key insight from the Institute for the Future report is that data production is an early rung on the ladder of product development and economic productivity. The worker of the future must be able to employ computational thinking to translate seemingly infinite amounts of data into actionable theories and models that add value to society. The ability to effectively “discriminate and filter information for importance” is key to augmenting data-based intelligence in a way that creates new industries and furthers economic productivity and human progress.

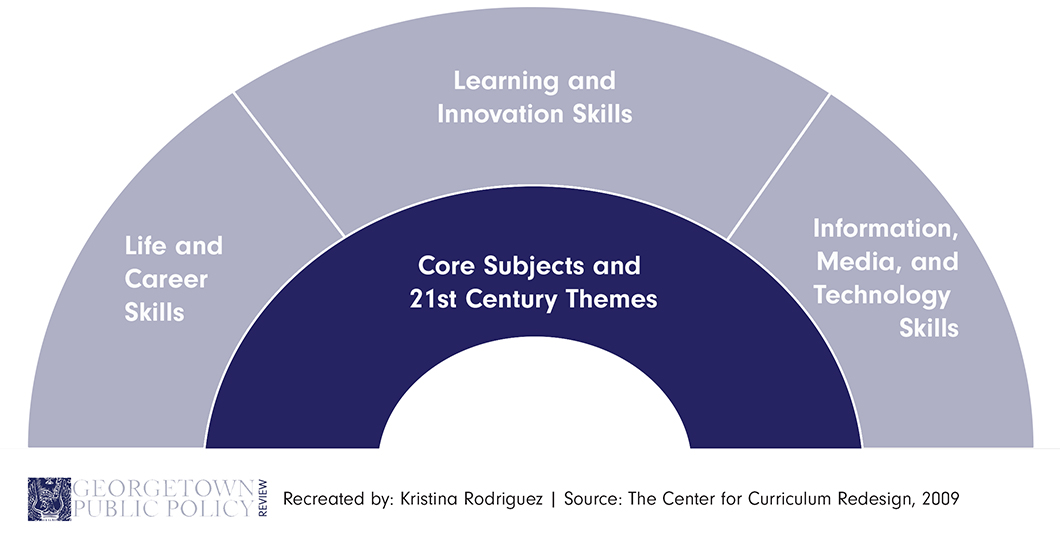

In 2009, The Center for Curriculum Redesign (CCR) designed and published a “21st Century Knowledge-and-Skills Rainbow” with the goal of showing how learning and innovation skills, digital literacy skills, and career and life skills can be seamlessly integrated into civic education schemes emphasizing issues like financial literacy and global awareness. Drawing on a group of experts from Fortune 500 companies, for-profit education firms, and education advocacy organizations, the authors of the report laid out 11 skills codified into three categories that illustrate clearly the value of augmenting intelligence. For example, skill areas such as “ICT Literary Skills” and “Media literacy” emphasize the need for future students to be able to gain actionable insight from digital technologies and media aggregation software.

CCR has since elaborated upon the initial listing of 21st Century Skills, laying out in a 2015 report the character features – mindfulness, curiosity, courage, resilience, ethics, and leadership – key to weathering technological automation and adding value to the future economy.

Conclusion

While the coming decades will not bring a robot revolution that renders the concept of human labor completely irrelevant, there is no denying a significant portion of current jobs will soon be automated. By augmenting intelligence with human capacity for problem solving, adaptation, and resilience and cross-disciplinary solution building, educators, policymakers, and corporate firms can create a new coupling of economic productivity and idea growth. To adapt to the challenges such automation poses to modern economic livelihoods, schools, as well as non-traditional mediums of learning, need to change curricula and pedagogy to reflect the value of 21st century soft skills in the labor market of the future.

Part 2 of this two-part series will discuss how educational organizations and governments can change pedagogies to ensure AI augmenting soft skills are taught effectively.

Christian Conroy is currently a dual Master in Public Policy (MPP) and Master of Science in Foreign Service (MSFS) candidate at Georgetown University, where he is focused on using econometric analysis to advise foreign companies entering emerging markets. Prior to Georgetown, Christian held several positions in the private sector, including Supply Chain Security Risk Analyst at BSI Group, Technical Advisor for Psychometrics and Analytics at GSX Inc., and Shanghai GM at CRCC Asia. Christian was also previously a Fulbright Fellow based in Xi’an, China, where he studied the decentralization of education policy with a focus on the distribution of authority between county bureaus of education and primary schools in rural China. His policy interests include technology disruption, smart city solutions, international development, big data, and just about anything related to China. You can find him on twitter @christianmconro.

This is an excellent, comprehensive and insightful overview of this really important issue. As a soft skills specialist I am working with helping people to see that they need to have well-developed soft skills to survive the technological ride. I am still one of the ones that believe that no matter how much of our future is taken over by machines, there is still going to be a need for that human connection. The people who have developed their skills in those areas will be those who successfully manage their futures.

Congratulations to Christian Conroy on this amazing article. It provides the reader with a great overview on how the world is unfolding in this century with the application of computerized workers. I’ve been trying to familiarize myself with the skills required for the type of workforce that this class of future employees will have to provide the computers and machines (maintenance, upgrades and/or creation). This generation of workers will have it even easier than other generations when we take into consideration the facility that children have when exposed to technology. However it is extremely important that they learn even more, that they use this advantage of being born in this time to expand their knowledge and to not stall with the information already given to them. And while we can easily solve this problem by taking action now i suggest to start teaching more about programming in school.