Most of the debate surrounding the United States drone program has focused on its legality and morality, while its effectiveness as a counterterrorism strategy has gone largely unquestioned. Although groups like the Taliban and Al Qaeda continue to operate in countries targeted by U.S. drone strikes, such as Pakistan, Yemen, and Afghanistan, the notion that the strikes have been effective is seldom challenged, largely due to the difficulty of empirical testing. My analysis questions this assumption and highlights the need for further research, showing a positive correlation between U.S. drone strikes and terrorist attacks in Pakistan.

There is plenty of discussion concerning the ethics of the drone program, but the public consensus seems to have concluded that targeted killing is an unpleasant necessity in U.S. counterterrorism, particularly in areas of the world where the American public is not willing to send its soldiers. Daniel Byman of the Brookings Institution makes the case that drones have had a substantial impact on Al Qaeda. More often than not, such defenses argue that drone strikes have supposedly been successful in taking out their intended, high-level targets (the public is rarely presented with evidence to support this claim, so we can’t assess its truthfulness). Former NSA director Michael Hayden used this reasoning in his defense of the program last year, and members of Congress gave similarly vague attestations of its effectiveness.

There is a dearth of quantitative analyses to back up these claims, as well as assessments of other counterterrorism programs, both because the programs are often fairly new and because the data is rarely available to the public. Many of the limited empirical studies that claim drones work sidestep the lack of data by instead analyzing the rate of leadership decapitation – assassinating a terrorist group’s leader– and conclude this tactic generally leads to the demise of the terrorist group. This is seen as indicative of the drone program’s success, since the strikes ostensibly target terrorist leaders, and supports the claims of effectiveness made by Hayden and others.

However, there is reason to believe that leadership decapitation is no longer an appropriate tactic to use against groups such as Al Qaeda and the Taliban. While targeting leaderships may have been effective in the past, in recent years Al Qaeda has adapted to American counterterrorism tactics by becoming more decentralized and less dependent on such high-level leaders. The Taliban in Pakistan has long relied on dispersed, smaller units. Because of this trend, the simple elimination of high-level leaders may not be a reliable indicator of the strength of a terrorism network as a whole.

Some journalists, analysts, and former military officials have suggested that the U.S. drone program may actually cause an increase in terrorist strength and activity, mainly due to its negative image in countries targeted by the strikes. The Washington Post and other outlets have reported that when civilians are killed in US drone strikes, terrorist groups are able to use local appetite for revenge and justice in their recruitment efforts. Many of these groups make a strong case for local public support, especially those that provide basic services to the local population. They are capable of setting themselves up as a somewhat viable alternative to unpopular national governments that cooperate with the United States. Most recently, Conor Friedersdorf of The Atlantic wrote that covert American drone strikes have emboldened Al Qaeda by simultaneously undermining the Yemeni government and bolstering the group’s support from Yemenis who must live with the fear of drones. These Yemenis have no way of knowing where or when the next strike will be, or who will lose innocent family and friends as collateral damage.

A few studies analyzed the U.S. drone program directly, including one conducted by Patrick Johnston of RAND Corporation and Anoop Sarbahi of Stanford University. Johnston and Sarbahi found that drones are correlated with a short-term decline in some types of terrorism in Pakistan. Another study found both a positive and negative relationship between drone strikes and terrorist activity in Afghanistan and Pakistan, depending on the Taliban faction targeted and the time period of the results. Needless to say, these two studies present conflicting conclusions on the effectiveness of the program.

The Study

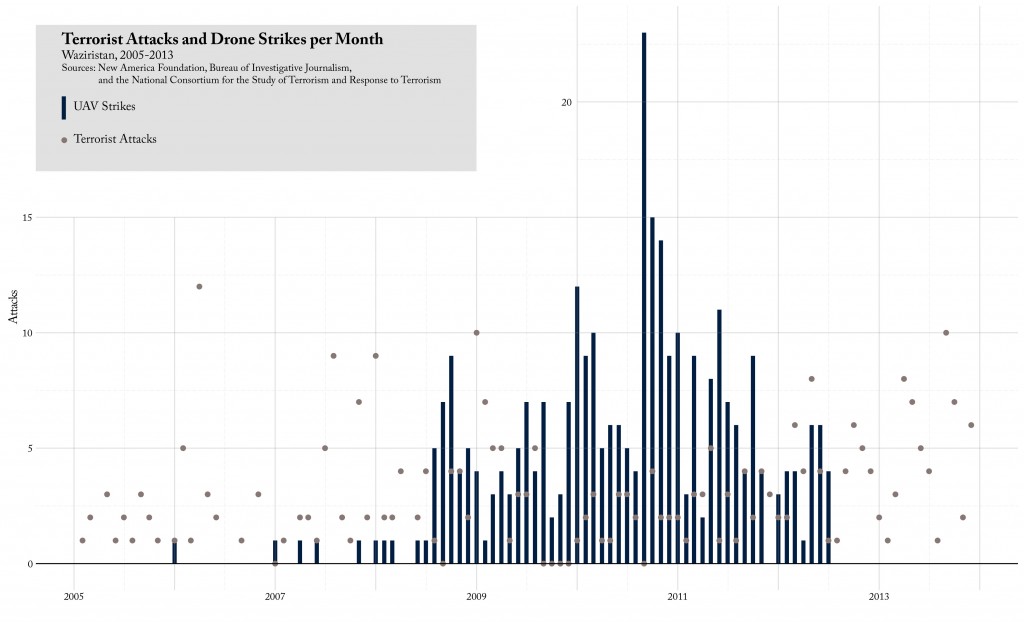

My research employs similar methodology, but makes some changes to the models used in previous studies. I collected drone strike data from the New America Foundation and the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, using only those strikes that are corroborated by both databases and were conducted in Pakistan between 2006 and 2012. I also used terrorism data for that same time period from the Global Terrorism Database.

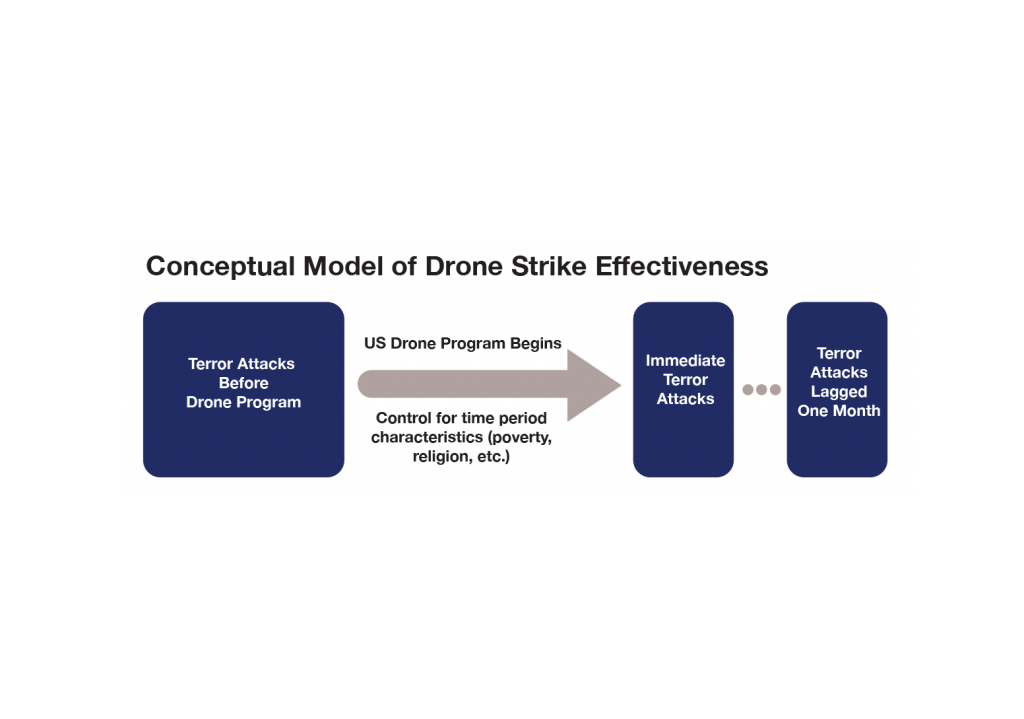

The model is similar to previous studies in that it assesses both the immediate effect of drone strikes on terrorism and the effect one month after a drone strike takes place, and that it uses fixed effects for the year and province of each drone strike. This means that the model controls for the fixed characteristics of the time period and location that might otherwise impact the frequency of terrorist attacks, such as poverty rates or religious makeup.

However, the model also differs from previous studies in that it examines the level of terrorist activity both before and after the U.S. drone program began targeting a specific province in Pakistan (what’s known as a difference-in-difference model). This model allows us to examine more precisely the before-and-after impact of the U.S. drone program on a specific area. This helps to eliminate some of the concern that might arise over reverse causality, or the idea that changes in the frequency of terrorist attacks influence the frequency of drone strikes, instead of the other way around. Examining the before-and-after levels of terrorism in each province makes it difficult to argue that the terrorist attacks are causing the level of drone strikes.

The model is limited, but the results are compelling: there is a statistically significant rise in the number of terrorist attacks occurring after the U.S. drone program begins targeting a given province. This effect is significant both immediately and one month after the drone strikes begin (see results below).

Of course, this study is a very early foundational piece of what will hopefully become a robust literature of quantitative analysis on the U.S. drone program, and counterterrorism programs more broadly. Its key limitation is that I could not obtain data on Pakistani military operations, which could also be a major cause of changes in terrorist activity levels. That said, it challenges the assumption that the U.S. drone program is a strategic success, and clarifies the glaring need for serious analysis of U.S. counterterrorism operations overseas.

Difference-in-difference model with two-way fixed effects and robust standard errors

| Terror Attacks | Terror Attacks (Lagged one month) | |

| postUAVstrike | 2.884***

(3.11) |

1.683*

(1.93) |

| Constant | 10.54***

(5.98) |

10.41***

(5.98) |

| Observations | 1,092 | 1,079 |

| R-squared | 0.578

|

0.576

|

| F( 96, 995) | 8.47 | 8.72 |

| Prob > F | 0.0000 | 0.000 |

T-statistics in parentheses

*** p<0.01, ** p<0.05, * p<0.1

What’s next for the U.S. drone program

Last Friday, the Office of the Director of National Intelligence for the Obama Administration released its first statistics on U.S. counterterrorism airstrikes outside of active combat zones from 2009-2015. Although the credibility of the government’s low estimate for non-combatant deaths has been questioned by many who have studied the drone program, the release does signal that this administration (and, hopefully, the next one) may be open to broader analyses of the program’s effectiveness. Escalating terror activity around the world necessitates a hard look at U.S. counterterrorism strategy as a whole.

This study encourages such analysis; if we can’t show that years of targeted killing has reduced terrorist attacks, the case for the drone program is much more difficult to make. The rise of ISIS and subsequent ISIS-inspired terror attacks around the world have shown us just how great of an impact decentralized terrorist activity can have, and how little top-down coordination is needed to carry out attacks. In this environment, it seems necessary to question whether killing individuals across disconnected groups and countries is truly an effective way to combat terrorism.

“Emily Manna is a policy analyst based in DC. You can follow her @emilymanna.”

Established in 1995, the Georgetown Public Policy Review is the McCourt School of Public Policy’s nonpartisan, graduate student-run publication. Our mission is to provide an outlet for innovative new thinkers and established policymakers to offer perspectives on the politics and policies that shape our nation and our world.

8 thoughts on “Exploring a Link Between Drone Strikes and Retaliation”

Comments are closed.