By: Kristine Johnston, Keith Ives, Jose I. Lobo, Simrin Makhija, and Miaomiao Shao

Though the number of civil wars and violent battles has decreased worldwide since the 1990s, our everyday news is still filled with accounts of political violence. In recent months, we’ve seen widespread violence in the CAR and South Sudan, and attacks by Boko Haram in Nigeria and by Al-Shabaab in Kenya.

Youth are often perpetrators of these acts of political violence, but there is mixed evidence on what leads them to participate. Scholar Ted Gurr’s famous relative deprivation theory posits that people rebel when they feel their situation is worse than what they deserve. In contrast, Oxford University’s Paul Collier and Anke Hoeffler, perhaps the most well-known researchers on civil war, conclude that rational calculations, based on economic opportunity and greed, play a significant role in explaining violence at the country level. Their findings suggest that employment programs could reduce the incentives for youth to join in violence against the state by increasing the opportunity costs of violence.

Mercy Corps, a non-governmental organization that works to improve peoples’ opportunities in conflict and disaster-affected countries, conducted its own field research and found that youth participate in violence for different reasons in different countries. Given the contradictory findings in the literature and in practice, Mercy Corps collaborated with a capstone team from Georgetown University’s McCourt School of Public Policy (MSPP) to research key factors associated with youth’s propensity toward political violence in Sub-Saharan Africa. Our goal was to explore what aspects of a young person’s life might lead him or her to participate in political violence, and to discover whether or not a country’s political, economic, and conflict context affects individual motivations for violence. The answers to these questions are crucial for creating policy and designing programs that reduce youth participation in political violence.

The Political Violence Literature

Figuring out what makes a young person take up arms is difficult. The Afrobarometer, a large database on citizens’ attitudes toward government and society, gives us some idea of how people feel about crime and political violence. It also measures factors frequently associated with political violence, such as employment, poverty, community membership, and social exclusion.

The findings from previous research are mixed on which factors matter, but there are some areas that have more agreement than others. Drawing on those areas of consensus, we developed several hypotheses:

- Youth who are actively engaged in society (through community groups or political organizations, for example) are more likely to engage in political violence because they have the networks necessary for linking with other violent actors and for mobilizing in political movements.

- In the case of civil war, unemployed youth may be more likely to join since their opportunity cost of doing so is low, and they may perceive potential economic gains. The sporadic nature of riots and protests and the unlikelihood of direct monetary benefits make this effect less likely in isolated incidents of political violence.

- If Gurr’s relative deprivation theory holds true, we would expect youth who feel they are being treated unfairly to be more violent. This could be reflected through feelings such as subjective poverty, exclusion, or ethnic discrimination.

- Different factors will matter based on the social, economic and political context in each country and the type of political violence prevalent. For instance, higher education for an individual may be associated with a lower likelihood of participating in political violence in a country with ample employment opportunities. Conversely, highly educated youth may be more likely to use violence for political means if they live in a country that has few employment opportunities for educated youth.

What the Data Say

Our team relied on Afrobarometer Round 5 survey data from 13 Sub-Saharan African countries in November 2013 (Benin, Botswana, Cape Verde, Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Malawi, Mauritius, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda, and Zimbabwe). We used a logit regression model to explore the correlates of youth political violence meaning that we looked to see how (if at all) youth’s willingness to engage in political violence changed as each of the hypothesized factors (such as education or education) changed. Included in the sample were survey respondents under the age of 35, reflecting the very broad definition of youth employed by the African Youth Charter, a political and legal document to promote and protect youth’s empowerment in Africa. Because the Afrobarometer survey is administered only to individuals 18 and older, our youth excludes younger teenagers who may participate in political violence.

The use of survey data, and the Afrobarometer data set specifically, has several limitations. It is impossible to know if people answered truthfully, or if those who chose not to respond to certain questions were more prone to violence than those who responded in full. Further, some of the variables may not have been measured most effectively. For example, questions about formal employment leave out the large percentage of people who work in the informal sector. Our study attempts to minimize the impact of these limitations on our results, but further research is recommended to determine the full extent of those limitations.

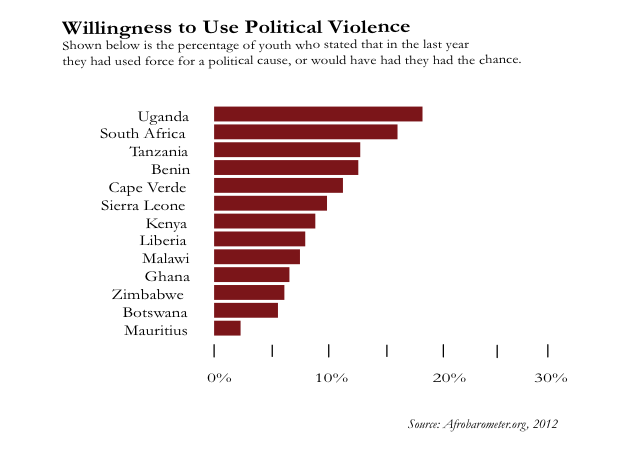

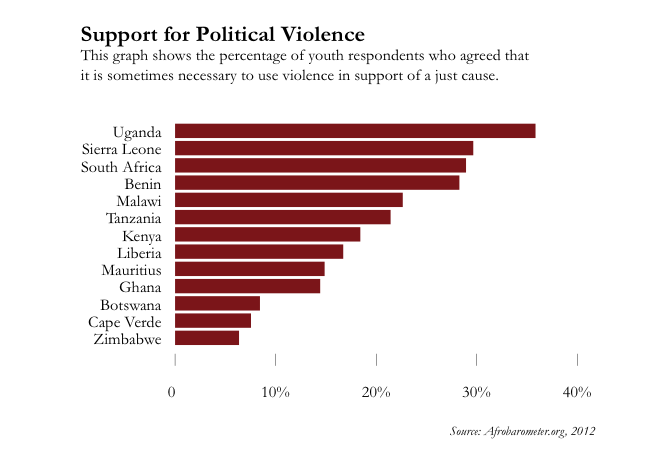

Our study examined two questions in the Afrobarometer survey: one that asked about willingness to participate in political violence, and one that measured support for political violence. The distributions of responses for each question across all 13 countries are shown in the graphs below.

Results were compared across the 13 countries and revealed few consistent results, even when the countries were sorted by region, Freedom House ranking (a measure of civil liberties), and type of violence. The factors that mattered the most varied substantially between each of the questions. We find evidence to both support and reject each of our hypotheses in at least one observed country.

- Experiences with corruption, a history of political action, and frequent contact with government officials were positively correlated with both willingness to participate in and support for political violence in at least half of the countries.

- History of attack in the household was another factor consistently positively associated with willingness to participate in political violence.

- The other factors most often associated with support for political violence were perceived unfairness of the law, unemployment, and active membership in community groups.

- Youth who believed their government was performing well in a number of economic and social areas were more likely to be willing to participate in political violence, but less likely to support it.

- An individual’s education level and employment status had no effect on willingness to participate in violence in most countries.

These results are consistent with the mixed literature on the subject, and reaffirm the importance of context. Further, the data confirm that traditional interventions, such as job training and civic education, should not claim universality, and signals the large role institutions play in understanding violence.

Context Matters

We assert that the historical, cultural, and political contexts in a country matter greatly when trying to identify the drivers of individual acts of violence. A young person’s motivations to engage in political violence will be different in a country with a free press and developing democratic institutions, like in Kenya, than they will for youth in Zimbabwe – the least free country in our sample. Similarly, living in a community recovering from a decade of war will create a different set of motivations for youth in Liberia and Sierra Leone.

Traditional Interventions are not Obvious Winners

Perhaps the more striking impression we are left with is the minimal results in traditional program areas such as education and employment. . We only find unemployment to be positively correlated with actual propensity to violence in one country (Liberia) and with support for violence in two countries (Benin and Sierra Leone). Education, another intervention workhorse, has a minimal relationship with propensity for violence, even when controlling for age, gender, and urban/rural location. Where it is significant, we do find primary and postsecondary education to consistently hold a negative relationship with violence.

Governance Institutions

The most consistent result across the sampled countries was the importance of factors related to government institutions. Corruption, political action, and frequent contact with government officials were positively related to both willingness to participate and support for violence in at least half of the countries. Varied results for other governance indicators, like exclusion under the law and perceptions of government performance, demonstrate that these are important areas to investigate when designing programs to address political violence in a country. This may be especially true for partly free or emerging democracies.

Recommendations

It is clear that the factors correlated with youth involvement in political violence vary by country, and in some cases factors that correspond with an increase in youth propensity for violence in one country are correlated with a decrease in other countries. The diverse results across these countries suggest that strategies to reduce political violence should be tailored to fit each country’s political, social, and economic context.

Overall, the finding across countries that those who have been attacked or who have had a household member recently attacked are far more likely to participate in political violence could suggest the importance of conflict mitigation programs and alternative avenues for expressing frustrations and grievances. It could also imply a responsibility of the government to ensure the personal safety of its citizens, which would not only reduce the number of attacks, but may also make people less likely to seek retribution on their own.

Providing training and opportunities for youth to positively engage their communities and government is crucially important. The data point toward a concern that individuals joining community groups, engaging in politics, and interacting with government officials may actually be more prone to violence. We commend programs that aim to help youth constructively engage in politics, while taking into account dysfunctional government institutions, like corruption, that could exacerbate frustrations.

Finally, concepts of exclusion and ethnic discrimination should continue to be addressed. Although not as correlated with violence as anticipated, these threats to social cohesion appear in many of the studied countries. Interventions, whether around civic engagement, security sector reform, or education, should be intentional in encouraging inclusion of political, ethnic, and social sub-groups.

A look at any given day’s newspaper will show you two things: that political violence is not going away any time soon and that it is not restricted to low-income countries, a certain type of government regime, or a specific region. Rather than throw up our hands, it is time to think critically about the rational calculations and decisions that youth make when deciding to engage in political violence. In doing so, we can use what we know to generate smart, highly targeted policy.

Kristine Johnston is a Research Analyst at Mathematica Policy Research and a recent graduate of the Master of International Development Policy program at MSPP. Prior to attending MSPP, Kristine worked with Project Muso Ladamunen in Mali and with Social Impact in Washington, DC. Her research interests include international development, impact evaluation, education, infrastructure development, urban planning, and bike sharing.