Pity the political analysts who cover special elections. A sample size of one House of Representatives race makes for a challenging exercise in interpretation. Yet, depending on the result, the race can be spun as a negative referendum on the president or a confirmation of his policy decisions.

Despite their relatively low predictive power, special elections are worth a second look. In particular, I will show that resignations, which have caused 101 (55.2 percent) of special elections since 1970, have crept up markedly in the past five years. For this article, I use a dataset of 183 special elections for the House of Representatives (all elections held from 1970 onward). You can access my dataset here.

Can Special Elections Predict the Political Future?

The jury is still out on the forecasting value, if any, of special elections for the House of Representatives. Gaddie, Bullock, and Buchanan, using a dataset of special elections from 1973 to 1997, found that the results of special elections seem to be subject to the same influences—spending, district demographics, and candidate experience—as typical open-seat elections. As such, they assert special elections likely do not function as a referendum on presidential administrations.

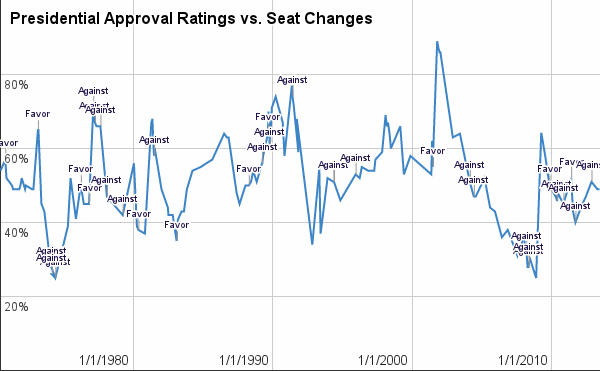

My dataset, expanded to include all recent special elections, yields similar results. The outcome of special elections, even for those that result in a party change, does not seem to be correlated with Gallup presidential approval ratings. The chart below shows approval ratings over time for each special election. Each election that resulted in a seat change is marked to indicate whether the change went in favor or against the current president’s party.

Taking a different approach, Smith and Brunell use a dataset of all special elections from 1900 to 2008 to see whether seat gains for Republicans or Democrats in special House elections will predict corresponding party gains for the general election. They find that, in instances where the special election resulted in a seat change (Democrat-held to Republican-held or vice-versa), the overall trend has some correlation with seat shifts in the next general election. When Republicans have a net gain of seats from special elections, 66.7 percent of the time they tend to win seats in the general election. When Democrats have a net gain from special elections, they win seats in the general election roughly 82.3 percent of the time.

While Smith and Brunell’s results are compelling, the timeframe of their analysis, extending back to 1900, might not have relevance for contemporary election contests. My dataset does not aim to reconstruct their results, but I do find that there is no significant correlation between seat changes and the majority party in the next election. Of the 40 seats that changed parties in my dataset, 21 matched the House of Representatives’ majority party in the next general election and 19 did not.

A More Productive Way to Analyze Special Elections: Look at the Cause

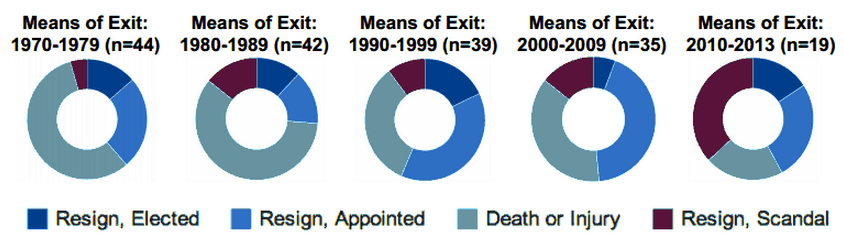

Generally, three events can trigger a special election: a member’s death or grievous injury, resignation due to scandal, or resignation due to a new position (elected office or other post).

Fortunately for current politicians, being a member of the House of Representatives seems to be less fatal than in the 1970s. From 1970 to 1979, 25 special elections occurred as a result of a death or injury in office. From 2000 to 2009, just 14 elections occurred in this way.

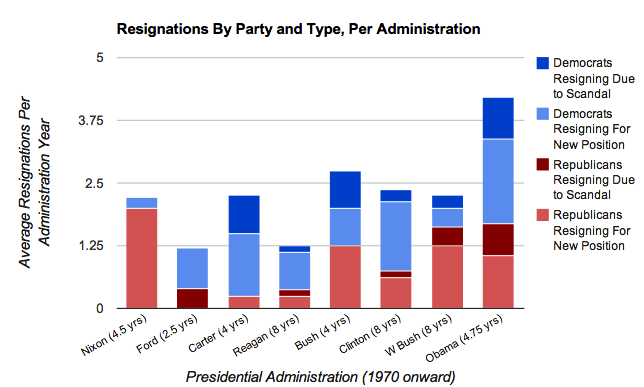

As deaths in office have declined, resignations from the House of Representatives –whether by choice or due to scandal – have, on average, stayed fairly constant until the late 2000s. Starting around 2008, the number of resignations from the House has risen markedly. The increase shown in the graph below is all the more notable given that there are three upcoming special elections from resignation – AL-1, MA-5, and LA-5 – that are not included in this chart.

Grouping resignations by presidential administration is a useful way of visualizing this change, but these variations might not be a function of who is in the Oval Office. Examining the cause of special elections by decade, we can see that the reasons members exit the House (and trigger a special election) have changed over time; elections triggered by a Representative’s death or injury are less frequent, while we see an increase in overall resignations.

Why this sudden rise in resignations? One source of the growth is the increase in resignations due to personal scandal. In particular, we see an increase in the number of resignations due to improper, but legal, behavior. There have been 23 resignations due to scandal since 1970, and seven of those have occurred in just the past four years. Only one of those seven involved conduct that led to a jail sentence. Of the disgrace-driven resignations in the previous forty years, two-thirds (10 out of 15) resulted in a jail sentence for the Representative.

Another source for the growth of resignations could be general discontent with the current state of national politics, particularly in the House of Representatives. The level of dysfunction on the Hill has come to a head with the current government shutdown, but we can see how recent resignations have been a warning sign for increased frustration in the House. While those who resign from office generally do not issue negative comments on their time in office, a couple of House members have begun to speak out.

Representative John Campbell (R-CA), who decided to step down this summer, told the Orange County Register, “[w]e have a dysfunctional president and it’s going to be hard to get anything done in the next three years.[…]Did that weigh into the decision? Yes, but it wasn’t the only reason.”

Also this summer, Representative Rodney Alexander (R-LA) resigned after citing the difficulties of strident partisanship in the House. In a statement, he wrote, “[r]ather than producing tangible solutions to better this nation, partisan posturing has created a legislative standstill. Unfortunately, I do not foresee this environment to change anytime soon.”

Writing for Washington Post’s The Fix, Chris Cillizza notes that recent resignations and retirements from Congress might stem from the fact that “[t]here’s no question that neither the House or Senate is a fun place to be at the moment.” He writes that these mid-term resignations may be the leading edge of a larger exodus from the Congress, particularly for members that hail from safe districts. This choice is understandable – former legislators can often find lucrative lobbying positions or influential state-level positions once they’re off the Hill.

The Importance of Special Elections

By my count, 59 of the current members of the House of Representatives were first elected to their positions via a special election. Regardless of the level of predictive power these elections carry, in the aggregate special elections are a potent source of new membership in Congress and a powerful indicator of sentiments on the Hill. They deserve a second look – one that glances beyond mid-season speculation and instead focuses on the collective impact of these unique contests.

This is the second of a two-part series analyzing special elections to the House of Representatives over the past forty years. The first post, examining the power of special elections to increase the numbers of women into Congress, can be found here.

Kristin Blagg is a student in the Master of Public Policy program with a focus in domestic social and economic policy. She has interned at Education Policy Program of the New America Foundation, in the Tennessee Department of Education, and in the office of former Representative John Olver (D-MA). Kristin spent four years as a math and science teacher prior to entering graduate school. She has a M.S. in Education from the Teacher U program at Hunter College and an A.B. in government from Harvard University.

2 thoughts on “Analysis: A Second Look at Special Elections in the House of Representatives”

Comments are closed.