Special elections have always commanded a certain, well, special level of attention. Reporters breathlessly cover the elections that emerge from scandal-tinged resignations. Pundits read returns like tea leaves for a referendum on presidential performance. Policy wonks contemplate the impact that the vacancy of a long-time incumbent’s seat has on Congressional negotiation. In short, special elections count.

Despite the national attention these off-season contests receive, there has been relatively little study on the outcomes of special elections themselves, particularly of contests that have occurred in the last decade.

In the first of a two-part series, I use a database of Congressional special elections from 1971 onward to reveal why we should be paying more thoughtful attention to these off-season contests. This first post shows that special elections could be a particularly potent pipeline for female legislators.

Defining a Special Election

Unlike Senate vacancies, which may be temporarily filled by appointment, the Constitution requires that House seats be filled by special election. My database catalogs all elections that resulted from the resignation or death of a representative or representative-elect. This includes special elections that were held on the day of the November general election, which are sometimes categorized as open seats rather than special elections. The database focuses on the broad circumstances and outcomes of elections and does not include information on defeated candidates or primary outcomes.

Special Elections: The Family Connection

Historically, it is relatively common for the wife of a deceased congressman to be elected to her husband’s vacant seat. The first woman to lead this trend, known as “widow’s succession,” was Mae Ella Nolan, who replaced her husband, Representative John I. Nolan, in 1923. Nolan was re-elected to a full term the following year.

More than thirty-five widowed women have followed their husbands into the House of Representatives. In recent years, the pattern of family succession seems to have grown more gender neutral. Since 2000, there have been four “family successors,” but only one, Doris Matsui, was a widow – the others were sons or grandsons of their predecessors.

Not Just For Widows Anymore

As a result of this phenomenon, much of the research on special elections as a pathway for women into politics has focused on teasing apart the “widow effect.” These studies have largely overlooked the broader implication: modern special elections seem to be especially powerful means for all women to ascend to Congress.

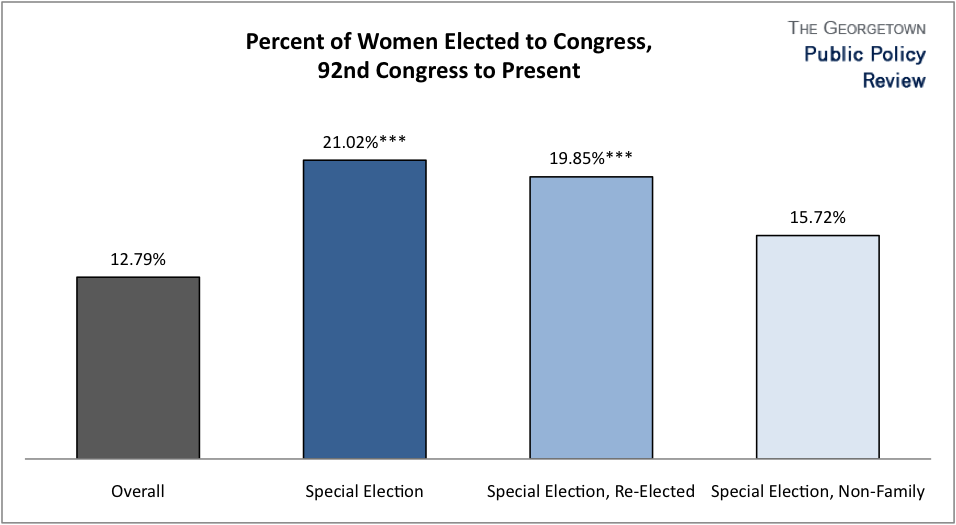

Of the 176 House special elections held since the election of the 92nd Congress in 1971, female candidates have won 21.02 percent. This number is significantly higher (p<0.01) than the 12.79 percent of women who were elected for the first time to the House by any election in this period.

A slightly lower percentage of women were re-elected after their special election (19.85 percent), but this number is still statistically significant (p<0.01). If we remove representatives with a family connection to the previous officeholder, we find that there is still a higher percentage (15.78 percent) of women who initially reach office by special election, but the difference is no longer statistically significant (p=0.157).

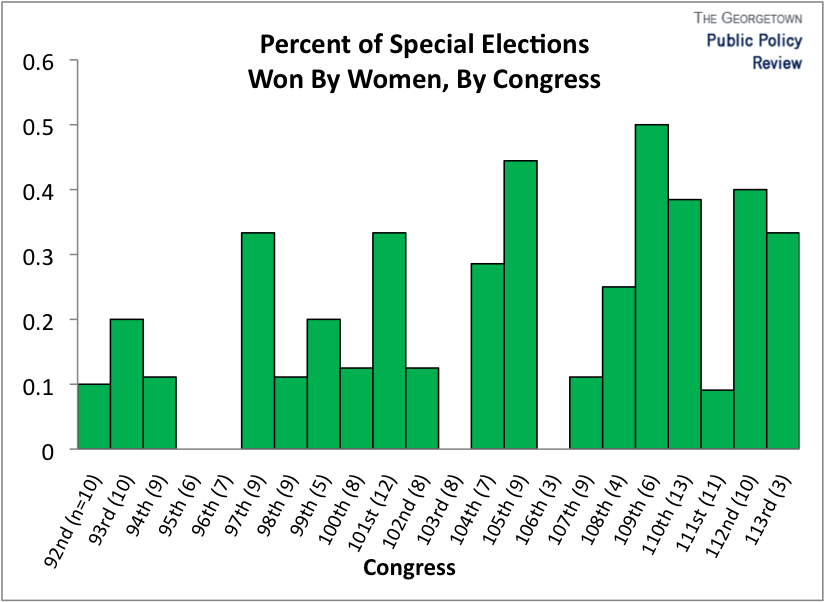

While the “widow’s succession” effect has diminished somewhat, the proportion of seats won by women in special elections has slowly increased, on average, over the past forty years. While the sample sizes are admittedly small, in four of the past ten Congresses, women have won the more than a third of special election contests.

Open Elections vs. Special Elections

Why might this effect exist? One plausible explanation is that special elections function in the same way as open-seat elections. The absence of an incumbent advantage means that there is a significant opportunity for women to secure seats. The 1992 “Year of the Woman” was, in part, the result of a bumper crop of 65 open House seats, which allowed for the election of 22 female legislators to these newly-vacant posts.

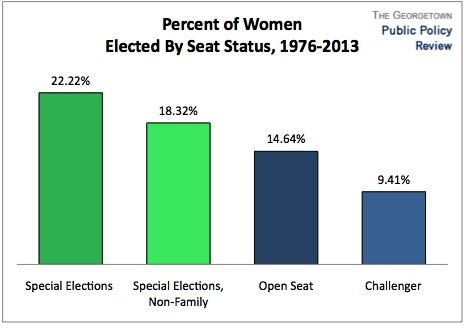

Are special elections significantly different from open seat elections? This question is harder to answer, but the answer could be yes. The Rutgers Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP) has a fact sheet on House elections from 1976 to 2012 that shows election winners by seat status. Their definition of open seat seems to be slightly different from mine, so I use their record of women who won as challengers to determine “true” open seats—seats that are not preceded by, or concurrent with, a special election.

By my count, there were 175 women first elected in this period: 43 as challengers, 100 in open races, and 32 in special elections. Correspondingly, from 1976 to 2012 there were 683 open seats from retirement, 457 seats lost to challengers, and 131 special elections. Based on these numbers, we see that the percent of women elected in special elections is higher than in open elections, even when excluding family members.

Because I source these numbers from multiple databases, there are some discrepancies that should be clarified by additional research. Nonetheless, this result aligns with a deeper regression analysis by Gaddie and Bullock that finds women are “as successful or more successful than their male counterparts” when they run in special elections.

The Legacy of Special Elections

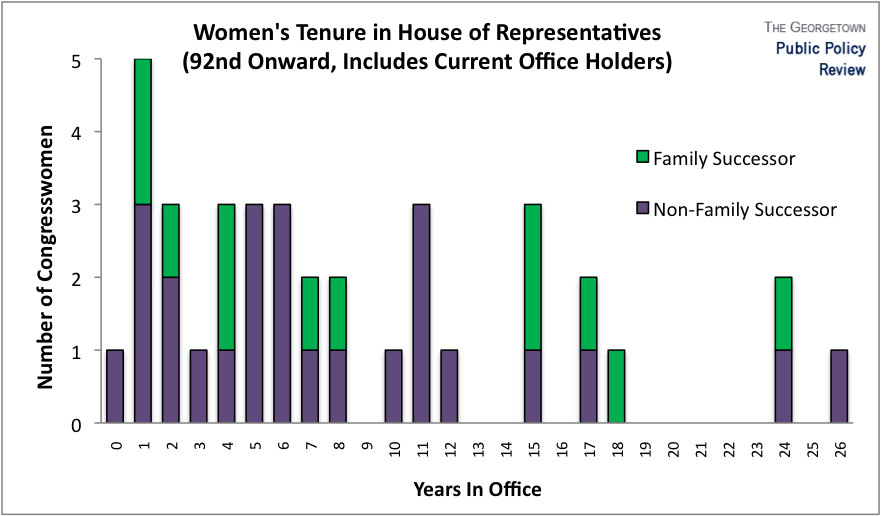

Even if the significant effect of special elections on female representation does in fact rely on the impact of “widow’s succession,” the influence of women elected through special elections cannot be denied. Women who win these contests are not “seat warmers”—only five of the 37 women elected since 1972 did not serve another term. Representatives Nancy Pelosi, Margaret Chase Smith, and Ileana Ros-Lehtinen all first reached the House via special election. Seventy-nine women are currently serving in the House of Representatives. Of those, fourteen initially won their seat through special election, even though there have been, on average, just eight such elections per Congress since 1972.

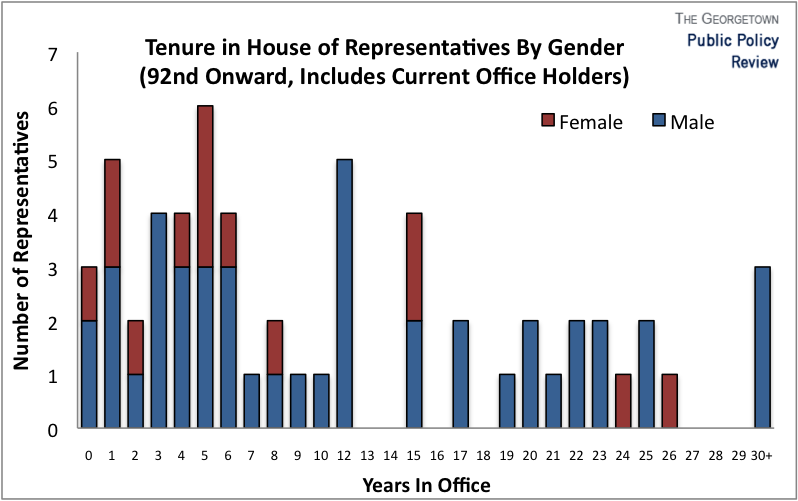

For now, there seems to be no significant difference for longevity in office, either compared to male representatives or by status as a widow. However, this effect may be further clarified as more women retire from elected office over time.

An additional effect that may deserve future study is the impact of gender continuity for individual seats. In the special election dataset, 80.95 percent of male-held seats were passed to men. Women vacated fifteen seats in the dataset. Of these, just five – 33.33 percent – were passed to other women.

While the history of women in special elections dates back ninety years, evidence of the success of female candidates from the past forty years show that these contests deserves a closer look. In the part two, I’ll look more closely at the circumstances surrounding special elections – such as the influences of party control and the means of resignation – to determine what can (and can’t) be said about the “specialness” of these contests.

Kristin Blagg is a student in the Master of Public Policy program with a focus in domestic social and economic policy. She has interned at Education Policy Program of the New America Foundation, in the Tennessee Department of Education, and in the office of former Representative John Olver (D-MA). Kristin spent four years as a math and science teacher prior to entering graduate school. She has a M.S. in Education from the Teacher U program at Hunter College and an A.B. in government from Harvard University.

Reblogged this on UK Women & Politics Specialist Group.